![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)

Vol. 26 No. 8

current issue

archive / search

contact

Past Opine interviews:

Lauren Berlant

Stephen Berry

John Boyer

David Cohen

Jerry Coyne

John Cunningham

Richard Epstein

John Frederick

Henry Frisch

Austan Goolsbee

Bernard Harcourt

Greg Jackson

Martin Marty

Martha Nussbaum

Raymond Pierrehumbert

José Quintáns

Jan-Marino Ramirez

Saskia Sassen

William Sewell

Herman Sinaiko

Geoffrey Stone

Cass Sunstein

Simon Swordy

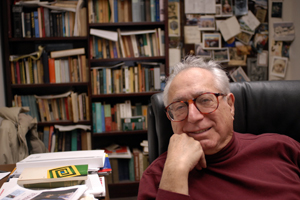

Opine: Herman Sinaiko

This week, Herman Sinaiko, Professor in the Humanities and the College, is of the opinion...

What book should every person read and why?

I can’t pick just one. First, Homer: The Iliad, to see concretely how rage, at its most intense and ultimately directed at our bodily mortality, can reveal the tragedy inherent in our all-too- human existence. And The Odyssey, to see just as concretely the extraordinary possibilities for some genuine satisfaction in the commonplace facts of our bodily mortality. Second, Plato: The Dialogues, to experience for ourselves the power of our unaided minds to question, explore and gain genuine insight into our unchanging nature and our contingent lives. Third, Shakespeare: the plays and sonnets. How can anybody who reads leave them off this sort of list?

Herman Sinaiko | |

If you could meet any scholar, author, composer, musician or entrepreneur, dead or alive, who would it be and why?

Socrates. I really want to know what it was like to talk to him.

Among the complex moral and political issues that affect humanity, which do you believe will never be resolved and why?

As Socrates seems to have understood very clearly, we all have opinions about how to resolve the moral and political issues that affect humanity, but that is all we have. Those opinions differ widely from each other, often conflicting, sometimes directly contradicting each other. Some are reasonable and seem prudent, some are not. But despite the frequent claims of certainty by those who hold them, none are beyond doubt. And given the diversities among us it seems unlikely that we will ever finally resolve any of them. From time to time we may do better, we may do worse, but every generation, in the future as in the past, will be faced with them. That is the perennial challenge that a liberal education seeks to meet.

If politicians had to pass an exam before they were allowed to serve in public office, what question would you add to the test?

Can you think of a single serious problem of our (or any) community that can be resolved by a technically competent expert without relying on mature prudential judgment? If they answer yes, they flunk.

If you could choose any three University professors and give them a one-year sabbatical together to solve a problem, develop a theory or make a discovery, who would they be, and what task would you assign them?

I would ask Joe Schwab, Confucius and Plato to design a liberal arts curriculum for this University that would actually liberally educate our extraordinary undergraduates in a way that would be relevant to the 21st century, and which could be accepted and taught by our talented and cantankerous 20th-century faculty.

Think of a renowned scholar from the past who added great value to your area of study. What would this person think of the advances that recently have been made in this field?

Hannah Arendt asked us “to think what we are doing” and showed us how to do that by articulating a whole range of unprecedented events in our world that needed to be thought about. I’m not sure that there has been much advance in thinking about “what we are doing” in recent years. I miss her.

What building on campus do you think is the most interesting architecturally and why?

Harper Library—the third floor reading room in particular. It comes as close as any room I have ever seen to embodying the ideal of a university as a place where people seriously read serious books.

Will a liberal arts education remain relevant to students in our increasingly technological society? Why or why not?

It better, or we’re all in for a much worse time than we have yet seen. See my answer to questions three and four above.

How will the next generation of scholars—today’s students—change your field in the decades to come?

I haven’t the faintest idea; I only hope whatever changes they make, they make them responsibly and thoughtfully. Otherwise we’re in for a lot more trouble than we’ve seen so far.

You didn’t ask me, but I’d like to tell you anyway what tradition I would like to establish or re-establish at this University. Professor Sinaiko is referring to a question previously asked of participants in Opine. — Ed.

Answer: The Lascivious Costume Ball was a genuinely spontaneous annual occasion created by our students about 40 years ago. It was immensely popular among the students and abhorred by the Undergraduate Advisors in the College Dean of Students Office because it was the advisors who served as chaperones at the event. I finally abolished it when I was Dean of Students in the College in the early ’80s, when the advisors, even under threat of losing their jobs, refused to supervise it any more.

Surely the combined intelligences at this University—students, faculty and administrators together—can figure out a way to allow students to have a hilarious night of obscene, sexual frivolity that can be appropriately supervised without killing its spirit. Our students deserve no less. After all, if the French could do it with the annual Beaux-Arts Ball in Paris in the 19th century, why can’t we do it at Chicago in the 21st?