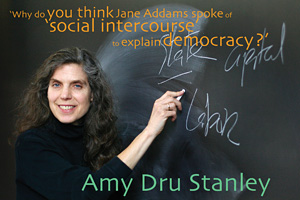

Amy Dru Stanley, Associate Professor in History and the College

By William Harmsw-harms@uchicago.edu

News Office

Photo by Beth Rooney Amy Dru Stanley |

|

When Amy Dru Stanley fires off a succession of questions for her history students to consider, she’s challenging them to think about the past in new ways and using inquiry to help clarify the meaning of historical transformation.

Students often come to a history course thinking that the endeavor is simply knowing facts, she said. Then, they have moments of deep confusion, uncertainty, even discomfort, when they realize that studying history entails not only figuring out which facts matter in explaining transformation over time, but also interpreting the meaning of practice and ideas.

“That’s when history starts looking more like deciphering philosophy or literature,” said Stanley, Associate Professor in History, who specializes in 19th-century U.S. history, legal and labor history, and women’s history.

Stanley identifies herself as a historian of ideas, recalling that she found inspiration in political theory courses with Sheldon Wolin as an undergraduate at Princeton University. Now she asks students to study theory historically. In the 19th-century section of the American Civilization core, Stanley might ask: “How did Lincoln reconcile hatred of slavery with fidelity to the constitution and opposition to the social equality of ex-slaves?” “Why do you think Jane Addams spoke of ‘social intercourse’ to explain democracy?”

Using Socratic questioning, Stanley encourages her students to dig beneath historical facts and ponder new and different perspectives.

“Suddenly, there is a realization that history is about ideology and symbolism and fact. There is a flash of illumination that you can sense in the classroom,” Stanley said.

“The confusion turns into excitement about the creativity of exercising thought about the past. And ideally that flash—the method of understanding—carries over to provoking new insights into the everyday world of the present.

“Ideas are in motion,” Stanley said as she explained the drama she finds in the stories of the past.

Take for instance the story of Sister Carrie, a novel by Theodore Dreiser, about a woman who becomes enthralled with the merchandise in the windows of Chicago department stores such as Marshall Field’s. How did that woman’s aspirations, which reflected fundamental change in people’s habits in the 19th century, jive with the nation’s legacy of anti-materialism passed down from the Puritans? Getting behind the window gazing to see what was going on in Carrie’s mind and in other, often unspoken, ways in the world around her is the point of the discussion.

To help students better understand that tension, Stanley uses contrasting texts to discover connections in unexpected ways and make analyses of the changes. Thorstein Veblen, one of the early professors of Economics at the University, gave some clues of how to think about the meanings of aspiring to affluence in his seminal work, The Theory of the Leisure Class.

The idea is not only to analyze the texts, but to juxtapose other forms of evidence so students make new connections on their own. “My lectures are a bit infamous for being accompanied by diagrams with myriad boxes and radiating lines and arrows—where I try to illustrate the interrelations of historical phenomena. What’s great is when students come to the board, take over the chalk and begin making their own diagrams to illustrate their claims,” she said.

It is at that intersection of contrasting works and perspectives that new perceptions can emerge, and students can examine broader issues, such as how power is organized in society.

The answers to those questions lie not simply in written texts, but in other artifacts such as songs, paintings and photography, which Stanley brings into the classroom. The aim is to gain deeper insight into the origin of prevailing ideas and the legal, cultural and political conflicts that generate social transformation, Stanley said.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)