Alumnus resurrects ‘on-the-road’ journey of lesser-known Beat poet

By Josh Schonwaldjschonwa@uchicago.edu

News Office

The film begins with Corso’s journey to discover his creative muse, following the death of Ginsberg. | |

| |

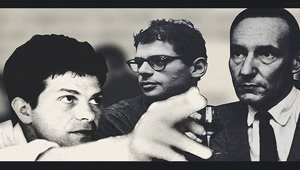

In his film, Corso—The Last Beat, Gus Reininger refers to the three men above as the inner circle of the Beat poets. From left to right are Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs; the photo was taken at a memorial service for Jack Kerouac. Corso led Ginsberg and Burroughs to Paris, to a run-down left bank hotel, where they lived for a year and where much of their most creative work, said Reininger, was written. Envisioning themselves merely as artists, the writers were mystified by their beatnik fame upon their return to America, when they learned of their counter-culture hero status. | |

Gus Reininger said he blames Doc Films for “subverting” him. Reininger (A.B.,’73) quit a successful career as a globe-trotting investment banker because, he said, “I learned in talking with film types in New York that, thanks to Doc, I know more about film-making than film-school grads.”

The economics major’s Doc-derived film knowledge paid off, when he impressed Miami Vice director Michael Mann and NBC executive Brandon Tartikoff with a seemingly unusual pitch: “Let’s do a version of Rainer Maria Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz about the Chicago mob.”

Reininger, perhaps best known for the fruit of the Fassbinder pitch, the late-1980s NBC drama Crime Story, is returning to the place where he became a cinephile to get feedback on his latest project—a decade-in-the-making examination of the life of the Beat poet Gregory Corso, who along with fellow writers Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, changed social and literary history.

A free, private screening of Reininger’s “Corso—The Last Beat” will begin at 4 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 23, in the Max Palevsky Cinema. After the screening, Reininger will answer questions from the audience. The film will not be publicly released until December 2009, after it has toured international film festivals.

For Reininger, previewing “The Last Beat” at his alma mater is a natural move. “This is not a film for baby boomers to relive their glory days. It’s for young people. It’s to introduce the icons of the Beat era to a generation that may not know them. I want to show young people how the Beats changed American society, paved the way for youth culture, the sexual revolution, even hip hop.”

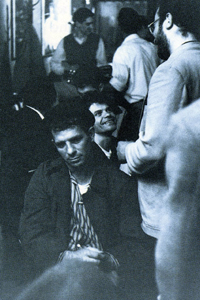

The photo shows a contemplative Kerouac sitting alone; Corso is seated behind him engaged in conversation. |

|

A longitudinal cinéma vérité-style documentary, “The Last Beat” follows Corso after the death of Ginsberg, as he goes “on the road” to discover his creative muse. Ethan Hawke, two-time Academy Award nominee, guides the audience through Corso’s odyssey. From Paris to Venice, Rome and Greece, Corso retraces the early days of “Beats” and his creative influence. Corso’s journey also takes him back to his old neighborhood Little Italy and New York’s Clinton State Prison, where he was imprisoned at 17 and read his way through his sentence under the tutelage of Mafia inmates, mostly notably Paul “Lucky” Luciano.

Though best known as co-creator of the cop-mob drama Crime Story, Reininger has nurtured a long interest in the poetry of Corso. His interest started when a priest at his Jesuit high school in Cincinnati named Corso as a “good Catholic writer.” Though this was, Reininger would soon conclude, a highly unusual characterization of Corso, the tip spurred Reininger’s interest in the Beats. “Corso was my first beat,” recalled Reininger, “then there was Ginsburg, Kerouac, which led to (Bob) Dylan.”

It wasn’t until the ’90s, though, that Reininger became interested in the Corso project. He appreciated the contributions of all the Beats, but Corso, the least-known figure, was his favorite. “He was the ancient poet,” he said. “He had this great preoccupation with ancient Greece.” Corso’s poetry, for Reininger, provoked flashbacks to his undergraduate days as a student of Herman Sinaiko, Professor in Humanities and the College.

It wasn’t easy persuading Corso to participate in the project, but after successfully answering a series of questions from the erudite Corso (such as “What is the first book ever written?” “Who is Gilgamesh’s best friend?”), Reininger earned his confidence.

Reininger calls the project more than just a film. “It’s a bit of a resurrection,” he said. Unlike Ginsberg and Burroughs, Corso sold his papers contemporaneously. As a result, they were scattered all around the United States, Italy and France.

“Any Ph.D. student who might find Corso a great dissertation topic, as he’s so under curated, would have a very difficult financial time traveling to so many libraries,” said Reininger. “Hence, there’s been a dearth of serious scholarship.”

With a research grant, Reininger and his collaborators hired a librarian to travel to 30 universities to find Corso’s papers and letters. A bibliography was constructed. The first product of the “The Corso Project” was a book titled, An Accidental Biography—the Letters of Gregory Corso. The project also assisted author Deborah Baker in her book, Blue Hand, The Beats in India. The project has recovered unpublished manuscripts, artifacts and photos, and has completed more than 300 hours of interviews.

But ultimately, Reininger’s chief objective is beyond scholarship. He is eager to introduce young people to the Beats, the role they have had on the current zeitgeist, and he hopes to introduce the world to the story of the most uncelebrated member of the group.

“Corso overcame abandonment, a life in the streets as a child of the Depression,” said Reininger. “He read his way through maximum-security prison, ended up as a poet in residence at Harvard, and ultimately met Alan Ginsberg and started the Beat movement. It’s a story of human triumph.”

Earlier screenings of “The Last Beat” with youth audiences at Harvard and Yale universities have been positive. “It’s hard to describe what it’s like to see students reach for a tissue when they see this story,” said Reininger. “It’s an enormously gratifying project.”

For more information on “Corso: The Last Beat,” please visit www.corsothefilm.com.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)