Philosophy for ‘limited beings’ accommodates approximations

By Josh SchonwaldNews Office

| |

Attention knowledge-seekers: It’s OK to give up the search for absolute precision. And, if you do give up the search, you could have a much deeper understanding of how the world works.

It’s not easy simplifying the work of William Wimsatt, the Peter B. Ritzma Professor in Philosophy and Evolutionary Biology. The creator and director of the College’s Big Problems program, who is widely known for his groundbreaking work in the philosophy of biology, Wimsatt’s writings pull from his polymathic interests in everything from evolutionary biology, developmental constraints, genetics and ecological systems, to cultural evolution, engineering physics and the history of science and technology.

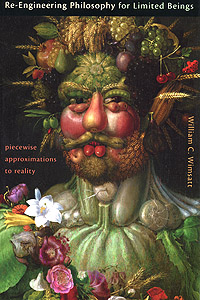

But there is one idea that emerges from these diverse outputs to explain the title of his recently published book, Re-engineering Philosophy for Limited Beings: Piecewise Approximations to Reality (Harvard Press, 2007). “Complex systems are messy,” said Wimsatt, gesturing to the 400-page synthesis of his work. “And human beings make errors trying to understand them. That’s OK. The goal should not be to eliminate errors, but to recognize and metabolize them.”

That is because, Wimsatt explains, “humans and organisms are engineered to be error-tolerant but still reliable. We learn, and re-engineer to do better. Evolved systems are complex and chaotic, but nonetheless ordered and robust.”

Wimsatt traces the origins of his error-tolerant philosophy to a class in magneto-aerodynamics that he took 35 years ago. Wimsatt entered Cornell University to study engineering physics. The son of a biologist who worked on reproduction and hibernation, he found his father’s work (he studied vampire bats and radio isotopes) fascinating, but thought it was “too messy to be paradigmatic science.” The young Wimsatt, who described himself as a “hard-core reductionist,” enthusiastically embraced the world of a physicist, worshipped the clarity and deductive power of classical mechanics, and, he said, “expected it to explain everything.”

William Wimsatt | |

But as a junior he audited the course (described in the book’s epilogue), which prompted his move away from, what he calls, an “enthralled worship of formalism and deductive precision.” On the first day, Wimsatt’s professor covered three boards with 22 equations—from Newton’s laws and the electromagnetic field equations to partial differential equations for hydrodynamic flow and compressible aerodynamics. The complexity of the material in the graduate-level magneto-aerodynamics class was intimidating. But the instructor told the class, “We can’t solve them exactly. So let’s make some simplifications and look at their qualitative behavior.”

To Wimsatt, this was a shock. In cutting-edge physics, where he expected high precision and rigor, he instead discovered “patches and approximations. Rules of thumb. Not exact solutions—as messy as biology—only with equations.”

The next year, Wimsatt left Cornell to work in industry, and to find and fix an important design error in a large run of special adding machines. Again, in another context, he encountered what he calls, “crucial seat-of-the-pants heuristic design principles. We would look for a solution that would work even if was not the ideal situation.”

This experience, said Wimsatt, has been consistently reinforced throughout his career—in encounters and collaborations with colleagues across the physical, biological and social sciences, and the humanities. But in philosophy it was very different.

“Philosophers seemed always to want to eliminate even the possibility of error up front,” he said. “Since that is not how things are done, can a philosophy for how things actually work be designed?”

Re-Engineering Philosophy is a powerful brief for how error-prone humans are trying to understand complex systems in the real world.

“Evolution makes robust, reliable systems, which we also need as philosophers and scientists—our approximations need to work,” said Wimsatt. In the book, Wimsatt analyzes key phenomena, principles and methods: reductionism, levels of organization and near-decomposability, the nature of heuristics, and how humans deal with processes of entrenchment that yield and constrain complex adaptive structures. “The goal,” Wimsatt writes, is that “our philosophy should be rooted in heuristics and models that work in practice, not only in principle.”

In the book’s first chapter, titled “Myths of LaPlacean Omniscience,” Wimsatt argues that evolution forms the natural world not as an all-seeing demon—as French astronomer and mathematician Pierre LaPlace characterized it—but rather as a “backwoods mechanic fixing and refashioning machines out of whatever is at hand.”

Wimsatt argues for the productive use of error-prone procedures and demonstrates how false models are crucial to knowledge production and develop truer theories. (Chapter 6 shows how, with 12 different kinds of tasks they can perform.)

“Bill Wimsatt is a visionary,” wrote Robert Batterman, professor of philosophy at the University of Western Ontario. “He’s a pioneer in displaying how messy and complex our world is, and in demonstrating how our idealized conceptions of the logic of science and the nature of our arguments need to be [changed] to capture and reflect the actual detailed practice and understanding of scientific investigations.”

Last week, writer Josh Schonwald interviewed Wimsatt to discuss his philosophy, his current work, and why he believes his “philosophy for limited beings” is valuable not only for philosophers and physical, biological and social scientists, but also students in the College. The complete audio transcript of the interview is available here: http://chronicle.uchicago.edu/wimsatt.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)