‘Master of metaphysical detective story’ teaching nonfiction class

By Josh SchonwaldNews Office

Ron Rosenbaum | |

Ron Rosenbaum, this year’s Robert Vare Nonfiction Writer-in-Residence, was once known as the “Dostoevsky of The Village Voice.” The filmmaker Errol Morris has called him “a master of the metaphysical detective story,” a nonfiction writer comparable to Jorge Luis Borges and Edgar Allen Poe. Others have compared him to writers such as Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson.

When Robert Vare (A.B.,’67, A.M.,’70), who created and funds the writer-in-residence program at the University, was asked if there was anyone writing now who reminded him of Rosenbaum, he paused, and said, “No one, really. There really is no one who resembles Ron in American journalism today.”

Indeed, over his 30-year career as the author of seven books and a contributor to a who’s who list of American periodicals, including The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, Harper’s Magazine, Vanity Fair, Esquire and Slate, Rosenbaum has assembled an almost dizzyingly eclectic oeuvre. He has written in different genres—lengthy investigative pieces, short opinion columns, exhaustive polemics, cultural essays and biting satires—and in such different styles as speculative, investigative, analytical, first-person, second-person and third-person, sometimes all within the same piece.

Then there is the staggering range of his interests. He has probed some of the weightiest issues of the day—the source of Hitler’s evil, the mystery of Watergate’s Deep Throat, the widespread paranoia in the CIA and the secret world of nuclear weapons—yet he also has examined the strategy behind a CharminŠ toilet paper ad campaign, profiled the inventor of canned laughter, penned a marriage proposal to Rosanne Cash and written a book about Shakespeare scholars.

Still, there is, within this seemingly disparate output, a detectable theme. Whether it is a first-person rumination or a third-person investigation, the work, Rosenbaum said, “Always begins with a question. Then follows a trail, follows an investigation, encounters conflict and contradictions, doesn’t always come to a neat conclusion, but leaves the reader thinking more deeply about questions he hadn’t considered as closely before. Even a cultural essay,” he said, “can be a kind of story.” And there is a calculated reason for this approach. “I think there’s something almost genetic in people that responds to storytelling.”

This belief and unique approach to nonfiction is precisely the reason Vare lured Rosenbaum to Chicago. The idea behind the 7-year-old Vare program is to inspire students by exposing them to some of the country’s best nonfiction writers. During this Spring Quarter, Rosenbaum is teaching what is arguably the most ambitious Vare Nonfiction Writer-in-Residence class to date: “Never Too Soon: Getting Started on Your First Nonfiction Book.”

The course aims to help a group of 10 students identify and develop their own story ideas into a book proposal. “He articulates his style and process in a very enlightening and entertaining way,” said Vare, who has worked with Rosenbaum. “It’s a very ambitious experiment but if anyone can pull it off and inspire a group of students, it’s Ron.”

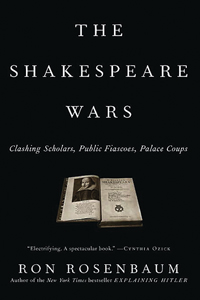

Vare also sees Rosenbaum and Chicago as a good fit because he writes about the life of the mind. His two most recent books, Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil and The Shakespeare Wars: Clashing Scholars, Public Fiascoes, Palace Coups, are examinations of intellectual controversies and involve extensive interviews with scholars. Rosenbaum has been a champion of the journalism of ideas, Vare said. “Ron recognizes that ideas are too important to be left to academics. He has healthy skepticism about experts and received wisdom.”

Rosenbaum will give a public lecture, titled “Shakespeare: The Terror of Pleasure,” at 5 p.m., Tuesday, April 17, in Room 122 of the Social Science Research Building. Shortly after his arrival in Chicago, Rosenbaum shared some of his insights and ideas about writing.

Many of your pieces take the form of a quest. What are the origins of this form?

When I was a kid, growing up in a boring suburb on Long Island, I discovered in the attic of my house, a cache of something like 50 of my father’s old Hardy Boy mysteries. I found myself longing to solve mysteries myself. I’ve always liked the kind of journalism that takes the quest form, as well. You go to a person and they tell you a story, then you go to the next person and they tell you something else, maybe something in conflict. You travel and you seek to find a way of resolving these contradictions or explaining where they come from and what agendas are behind the differences.

You left graduate school in literature for journalism. Why? And why have you turned back, later in your career, to the world of the ideas?

A turning point occurred in graduate school, at Yale, when I attended a seminar on Chaucer’s minor poems, his Love Vision poems. I asked the scholar a question at the end of his talk about what he felt Chaucer’s attitude to the reality of love was. His answer was, ‘Love is such an uninteresting question. The real interesting question is about the making of poetry.’ Now, I think the making of poetry is an interesting question, but I don’t think love is an uninteresting question. There were still questions that mattered to me and I felt that graduate school wouldn’t teach me anything about them. I felt that it would be an insular, hermetic experience that would confine me in the sealed chamber of academia, and I also had this desire to hang out with cops and criminals—and not just to read about them. I got a few lucky breaks—a job at the Village Voice, a job as a contributing editor at Esquire; jobs that allowed me to experience journalism as a great adventure and to travel across the country pursuing stories that mattered to me.

I was hanging out with cops and criminals, and I suppose I went through an anti-academic, anti-intellectual period, but I never stopped caring about literature or intellectual controversies, or being interested in reading scholarship. Over the years, though, I found more and more that the stories that interested me had at their core an intellectual or metaphysical element.

You’ve said that a big moment in your career was when you wrote about “nuclear porn?”

I was investigating the hidden underground world of nuclear weapons for Harper’s in the late ’70s. I was visiting missile silos, underground nuclear command posts, the hollowed out mountain in Colorado that was the North American defense command.

But I also was encouraged by the editor Lewis Lapham to do more—I did cultural analysis of what I called “Nuclear porn”—all the novels and films that had the world on the brink of a climactic explosion—and paralleled that with an analysis of the theoretics of nuclear escalation by the real-world nuclear strategists and game theorists.

I incorporated all three of the forms—first-person investigation, cultural analysis, intellectual speculation—in the piece. And discovering I could combine these different modes of writing was a turning point. I could be out in the world discovering things, but I could also be experiencing the intellectual excitement of things like nuke strategy. It was part of a gradual process, a shift to intellectual and cultural controversies. So I left the world of scholarship to do journalism, but then I found that I was increasingly doing journalism about scholarship.

You’ve said that “close reading” is of great value to your work as a journalist. How does a scholarly background inform your writing?

I was and still am an English-major nerd. And, yes, the close reading of poetry, a skill I learned at Yale, has perhaps been the thing that’s most influential on my journalism, in the best of my work. Close reading teaches you to tease out ambiguities. What I discovered was that this sort of thing can be directly applicable to journalistic subjects. Autopsy reports, court transcripts, Congressional hearings—these are documents that are not literary in intent, but nonetheless that yield unexpected insights if you apply a kind of literary attentiveness to them.

And there’s no doubt that literature has influenced my journalism—reading Henry, Fielding, Victorian novelists, Trollope, Dickens—especially Dickens, for his vast intricate vision of society, and especially for his narrative energy. And Shakespeare for the kind of heights human beings are able to attain and a sense of tragedy. I wouldn’t claim that you should read literature for its practical value in the news room, but on the other hand, the great journalists that I respect the most are ones who are steeped in literature, people like Tom Wolfe, Murray Kempton. They brought to reporting a Dickensian sense of the world. So you know, it may not get into the story. City editors don’t welcome extended digressions on the Dickensian underworld of the Victorian era, but the literature of the past can help shape the mind that’s apprehending the stuff of the present.

My first attention-getting piece of long nonfiction was when I entered this whole network of blind, electronic phone phreak geniuses and proto-computer hackers like the legendary “Captain Crunch” (“The Secrets of the Little Blue Box,” Esquire, October 1971). Immediately it seemed to me like I was entering the world of Pynchon’s novel The Crying of Lot 49. Having read Pynchon gave me a kind of vision of this world that I wouldn’t have had otherwise.

After hundreds of years of scholarship, countless biographies, essays, etc., what lingering mystery did you find in the world of Shakespeare scholarship that compelled you to undertake The Shakespeare Wars?

| |

Initially what gave me the impetus to do the book was a parallel between the “exceptionalist question” in Hitler and Shakespeare. I had spent 10 years examining controversies over the origin of Hitler’s hatred. And the exceptionalist debate in Hitler studies is whether Hitler is on the continuum of other evil doers, just on the very far extreme end but still explainable by the same means that we explain other evil doers. Or did Hitler create a realm of “radical evil” that is off the grid, off the continuum? It occurred to me that a similar question could be asked of Shakespeare. Is he on the continuum of great writers? Or is there something about Shakespeare that is beyond that? That’s where it started out.

But then I entered the world of Shakespearean textual scholarship, which is unlike what you might think when you first hear the phrase—not a world of dusty pedants; these are brilliant scholars engaged in genuinely exciting controversies. What is the true Shakespearean variant? Is it the result of Shakespeare’s own revisions, or someone else?

I fascinated by the arguments over a controversial new edition of Hamlet— which prints not one, not two, but three early text versions of Hamlet—each with variations that affected the aesthetic and thematic nature of the work. I examined similar controversies over King Lear. And I was also fascinated by the controversies in the theatre—the passions that directors brought to the way the iambic pentameter lines should be spoken by actors. When I talked with Sir Peter Hall, he was banging on the table, “It’s got to be this way. There must be a slight pause, at the end of each line to give line structure its integrity.” Others disagree; others suggest different meanings for that slight pause. The fact that there were so many unresolved controversies and not just controversies that go to settle academic points, but controversies that go to the very heart of the thematic and aesthetic impact of Shakespeare’s work, made it add up to a book.

Tell us about your upcoming lecture based on The Shakespeare Wars, titled “The Terror of Pleasure.”

It comes from my theory about Theory with a capital T. Theory being an imprecise word for what I feel is the way people construct intellectual scaffolding that distances them from works of literature.

It started with my excitement from what I gain from close reading. If a word is ambiguous, one’s job isn’t to decide which of two or three or seven meanings is the correct one, but rather to tease out the possibilities of each. Because that’s what great poetry is, a spectrum of possibilities that increase your excitement about what the poet is doing. To me it was really an exciting way of learning to read. And it brought you closer to the almost unbearable excitement of great poetry and literature. My feeling is that for a couple of generations there was a reaction to this closeness. It was almost scary to be that close to so much intense pleasure. There’s a kind of terror of this pleasure; it threatens to dissolve the identity. Result: the defensive distancing I spoke of.

This is not my idea; others have said this as well. And they’ve said that one thing that great literature can do is to invoke a sort of terror of the abyss—of the bottomless possibilities of meaning. Beauty has a kind of power that’s almost terrifying; I think that what happened to a couple of generations of literature students and their professors—not all by any means, not many here— is that they got frightened of literature and developed elaborate scaffoldings of theories that distanced themselves from literature. And they approached it from a distance and only through the lens of theory, rather than risk the almost radioactive danger of literature’s pleasure. It’s not true of everyone who writes about Shakespeare; a lot of people write brilliantly about Shakespeare. It’s not true of everyone who writes about literature, everyone in graduate school, every professor. But certainly, if you read the academic journals like I have over the years and you see the meta-theorizing, it seems to me there is this terror of pleasure. Protecting oneself from the literature. That explains the title. But in the talk, I hope to touch on a number of the controversies in The Shakespeare Wars.

The class you’re teaching at Chicago has the ambitious goal of helping students get a book underway. Why are you encouraging students to aim for a book, rather than magazine or newspaper writing?

I first started thinking about this in 1998 or ’99. I was teaching “literary journalism” at Columbia’s journalism school, and I began to feel guilty. I felt that I was encouraging my students to try to do stories for which there was no longer a market. I started to do journalism at a time when editors would publish 10- to 15,000-word odysseys. You’ll still occasionally find places that will do that, but it’s rare. I love that kind of magazine piece. I love reading it, but who was going to publish it now? They asked me back to Columbia, at least twice, and I said no. I couldn’t do it. And then a few years later, NYU asked me to teach. I sensed a shift in the landscape; the kind of interesting long-form nonfiction that used to be published in magazines was being published in short nonfiction books by young writers. That’s where the good stuff was. One example is Laura Kipnis’ Against Love. It’s a long cultural essay under 200 pages. It’s a funny, contrarian polemic about a subject that concerns everyone . . . and she says something that hasn’t been said before about love in an entertaining, smart, provocative way.

Magazine editors are not looking for new writers to do 15,000-word pieces. Yet book editors are eager; there’s an expanded market for the 50- to 60,000-word nonfiction book. If you go to Borders and Barnes & Noble, you’ll see books by all kinds of first- time writers.

I see some college writing courses, teaching people creative nonfiction, which sometimes seems to be teaching writers how to write misty water-colored memories of their youth, or what I learned on my summer break. It can develop one’s craft I guess, but in terms of getting published, that road often leads nowhere. I feel like I can at least do people a service. If they’re interested in becoming a writer, I can give them an idea of what’s a book, what’s not a book. If you have something that you think is a book, how to express what it is, how to begin writing it. In some way take that first step to becoming a writer. If you’re writing memoirs of your youth or summer break, you have to be either a genius or a serial killer, to get it published . . . Maybe it seems less ethereal, but I’d like to be practical . . . I’d like to help people who want to be published writers.

You’ve urged journalism schools to put more emphasis on the journalism of ideas. Can you elaborate on this?

Another turning point in my career was my piece on Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. I was always skeptical of the knee-jerk acceptance by the entire American culture of Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ five stages of death and dying, which had no genuine corroboration except for self-fulfilling anecdotal responses from tired health care people who liked the idea that Kubler-Ross’ five stages ended up with the patients being quiet and not bothering the nurses. That investigation began to make me aware that the agendas behind ideas are more often as interesting as what the ideas themselves purport to explain. Look for the agendas. Question what is received wisdom. That’s what I’ve told students. The post-Watergate reporting mantra: follow the money, find the money that caused the corruption in politics, is still true. But follow the ideas is another worthy objective because a lot of ideas and a lot of received wisdom are unexamined and accepted as true, without necessarily much foundation. Hidden agendas deserve to be exposed.

And I’ve also learned that it’s worth going beyond examining what scholars write. You can sometimes get to the heart of the matter of scholarly disagreements by actually sitting down and talking to them about it. Often scholars change their mind, emphasize different things, sometimes they want to pick fights with other scholars, sometimes they’ll have interesting reactions to your perception of their work, or you discover in a footnote they’ve done that there’s some totally fascinating aspect of their work that they’ve relegated to a footnote, and they’d love to talk about it. A lot of revelations come out of footnotes.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)