Art historian examines abundance, excess of French Renaissance through art, literature, architecture

By Josh SchonwaldNews Office

| |

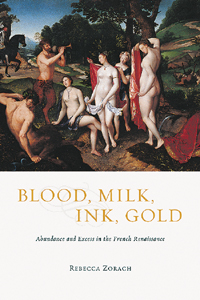

Rebecca Zorach, Assistant Professor in Art History and the College, has won the 2006 Gustave O. Arlt Award from the Council of Graduate Schools. Each year, the council recognizes a promising young humanist who has written a book deemed to be an outstanding contribution to humanities scholarship. Zorach, a specialist in late medieval and Renaissance art, was recognized for her groundbreaking book, Blood, Milk, Ink, Gold: Abundance and Excess in the French Renaissance, published by the University Press.

The Society for the Study of Early Modern Women also honored Zorach as a co-recipient of its 2005 book prize for the best book relating to women and gender in the early modern period.

Zorach’s winning book is an interdisciplinary look at the visual culture of the French Renaissance, connecting multiple forms of art with social, economic and political forces of the period. Mary Sheriff, a University of North Carolina art historian who reviewed the book wrote, “It offers new possibilities for configuring a cultural history of any period.” Evelyn Welch of University of London called it “an exciting, innovative perspective . . . should be essential reading for art historians and historians alike.”

“Zorach’s book has clearly established her as one of the leading young art historians of a new generation,” said Danielle Allen, Dean of the Division of the Humanities. “Her theme is the multiplicity of symbolic and aesthetic meaning, a resource with which the French monarch could reinforce his own authority and artists could extend their conversations outside the programmatic reach of royal ideology. Her book offers a remarkably rich, synthetic account of French culture.”

In the book, Zorach focuses on a period of French art that has been the subject of relatively little scholarship. While art historians have closely examined Italian and Dutch art of the Renaissance, French works of the 16th century are less celebrated. Consequently, art historians have overlooked this period, said Zorach, leaving its study largely to French museum curators, who tend to think more in terms of style and attribution than the cultural and political issues, which inform her research.

While doing research in France in 1995, Zorach, who began her scholarly career as a late medievalist, grew increasingly interested in this extravagant and tumultuous period. Sixteenth-century French kings, believing they were the heirs to imperial Rome, commissioned a magnificent array of visual arts to secure their hopes of political ascendancy.

Specifically, Zorach, who had a particular interest in gender studies, began to look at the ways in which representations of women and gender were intertwined with economics in the architecture, art and literature of the period. A whole genre of literature, for instance, in late 15th-century France, was called the “Markets of Love.” At the Chateau of Fontainebleau near Paris, the female body often was used in sculptural ornamentation and in the frames of paintings. In this period of exuberant abundance, Zorach discovered, the female body also was used to represent wealth. “I started to identify an ‘ethos’ or ‘visual rhetoric’ of abundance in the French Renaissance, and to think about the complex ways it functioned culturally and aesthetically.”

Zorach’s interest evolved into a sweeping examination of the visual arts of the French Renaissance. From marvelous works by Francois Clouet, to oversexed ornamental prints, to Benvenuto Cellini’s golden saltcellar fashioned for Francis I, she looks at depictions of sacrifice, luxury, fertility, violence and sexual excess, as well as the contemporary critiques and commentary they engendered. And throughout this cultural history, abundance and excess flow in liquid forms—blood, milk, ink and molten gold.

“I structured the book, as the title suggests, as a series of substances that helped me think through the symbolic meanings and values of matter in 16th-century French culture,” she said, “in the performances of power, gender and resistance, and in the invention of new ways of thinking about the pleasures of art.”

Zorach noted that her dissertation was to her advantage in winning the Arlt award. “My dissertation was structured more like a book than a dissertation,” she said, “I always envisioned it this way.”

Another outgrowth of her dissertation was her work on the exhibition “Paper Museums: The Reproductive Print in Europe” at the Smart Museum of Art, which she co-curated two years ago. Through the prints of Albrecht Dčrer, Claude Lorrain, J.M.W. Turner and Marcantonio Raimondi, who collaborated with Raphael, the exhibition showcased the impact that printing had on conceptions of art and art making.

Zorach received both her M.A. and Ph.D. in Art History from Chicago in 1994 and 1999, respectively.

Before her appointment as an Associate Professor in Art History in 2003, Zorach was a Harper-Schmidt Fellow and a Collegiate Assistant Professor in the Humanities and the College.

Zorach is currently working on several projects, including another exhibition, titled “The Virtual Tourist in Renaissance Rome,” scheduled to open next fall at the Special Collections Research Center in the Joseph Regenstein Library. This show will display the library’s rare collection of Renaissance prints of Roman antiquities and monuments—the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae—and related books.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)