Sharing common knowledge can impede sharing of new information

By William HarmsNews Office

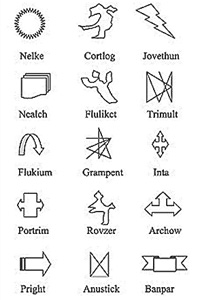

Shown above are some of the shapes of the stimulus objects and their names, which were used in the study. | |

Some of people’s biggest communication problems come when sharing new information with people they know well, according to newly published research in the Department of Psychology.

Because they already share quite a bit of common knowledge, people often use short, ambiguous messages in talking with co-workers and spouses, and unintentionally create misunderstandings, said Boaz Keysar, Professor in Psychology and the College.

“People are so used to talking with those with whom they already share a great deal of information, that when they have something really new to share, they often present it in a way that assumes the other person already knows it,” said Keysar. He and graduate student Shali Wu tested his communication theories and presented the results in an article, “The Effect of Information Overlap on Communication Effectiveness,” published in the current issue of Cognitive Science.

When people share additional information, communication effectiveness is reduced, the researchers wrote, “precisely when there is an opportunity to inform—when people communicate information only they themselves know.”

In order to test the theory, Keysar and Wu created a communications game in which parties had unequal amounts of information. The researchers prepared line drawings of unusual shapes and gave them made-up names, and then trained University students to recognize different numbers of the shapes.

During the game, students were tested to see how well they could communicate to a partner the identity of one of the shapes. Students who with their partners shared a great deal of knowledge about the shapes, used names more often in identifying the shapes, while students who did not have a great knowledge of the shapes described the shapes rather than naming them.

The students who shared new information about the shapes were more likely to confuse their partners because they would automatically use the name of a shape rather than provide a description, assuming that their partner would know what they were talking about, when in reality their partner did not recognize the name.

The use of unknown names slowed communication, just as the use of unknown information slows communication in real life. The researchers found that people who shared more information were twice as likely to ask for clarification as those who shared less information.

In real life situations, the assumptions people make about what another person knows can have many consequences, Keysar said. Doctors, for instance, who often communicate quickly with each other, can miscommunicate because one physician may not realize the other physician is getting new information when they are discussing a treatment program, said Keysar.

On a professional level, brief e-mails between colleagues can cause miscommunication, Keysar has learned from personal experience. “I once was scheduled to speak and had gotten the day of my talk mixed up. I received an e-mail from the host asking me if I was OK. I wrote back and said I was and didn’t find out until later that what he really wanted to know was where I was, as they were waiting for me to talk,” Keysar said.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)