Evidence of battle at Hamoukar points to early urban development

By William HarmsNews Office

Above is a sample of three sling bullets made of clay and found in the collapsed, burnt buildings at the Hamoukar site in Syria. | |

New details about the tragic end of one of the world’s earliest cities, as well as clues about how urban life may have begun there, were revealed in a recent excavation conducted in northeastern Syria by archaeologists from the Oriental Institute and the Syrian Department of Antiquities.

“The attack must have been swift and intense. Buildings collapsed, burning out of control, burying everything in them under vast piles of rubble,” said Clemens Reichel, the American co-director of the Syrian-American Archaeological Expedition to Hamoukar. Reichel, a Research Associate in the Oriental Institute, added that the assault probably left the residents destitute as they buried their dead in the ruins of the city.

Reichel’s assessment of this battle, which occurred around 3500 B.C., was made after a field season in September and October of 2006 at Hamoukar, a large archeological site located close to Syria’s border with Iraq. Having excavated at Hamoukar since 1999, the team this season uncovered further evidence of the accomplishments of the inhabitants among the remains of a walled city that dates to the fourth millennium B.C.

In addition to the city’s wall, the mission continued to excavate quasi-industrial installations and two large administrative buildings that had been destroyed by an intense fire. Mixed in with the debris from collapsed walls, more than 2,300 egg-shaped sling bullets were found. This discovery led the excavators to conclude that an early act of warfare had brought the settlement to its end.

These remains of a body were found in a burial pit that had been dug into the ruins of a destroyed building in Area B. It is likely the person was a war casualty. Twelve graves were found at the site. | |

Evidence for warfare was first reported in 2005, but this season the excavators found gruesome details associated with the preparation for the battle and the aftermath. “We found sling bullets at literally all stages of use, from manufacture to impact,” Reichel said, pointing out that the team found a sling bullet that had pierced the plaster of a mud brick wall.

Hamoukar’s defenders resisted the attack using all facilities and materials available, a fact highlighted by discoveries in a shallow pit in the floor of one of the rooms. Ordinarily, this pit, into which a water jar has been buried to its rim, would have been used for soaking discarded clay seals for recycling into fresh clay, but two-dozen sling bullets found neatly lined up along its edge indicated that the pit also had been used to make sling bullets during the city’s final hours.

“It looks as if they were—quite literally—throwing everything they could find against the aggressors,” Reichel said. The team also found 12 graves in the debris, very likely of people killed in the battle.

Three views of obsidian cores found in the southern extension of the site show blade-napping in the grooves. | |

Hamoukar was on a key trade route that led from Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) across northern Syria and the river Tigris into southern Mesopotamia. Some evidence of this long-lasting trade was found in an area to the south of Hamoukar’s main site—a large mound. The team found obsidian fragments in an area of more than 700 acres (280 hectares), which they dated to 4,500 to 4,000 B.C. using pottery fragments found with the obsidian. In addition to tools and blades, the team found large amounts of production debris such as obsidian cores, a discovery that is even more significant than finding actual tools.

“Finding cores and other production debris tells us that they are not just using these tools here, they are making them here,” explained Salam al-Kuntar, the Syrian co-director of the expedition. Obsidian does not occur around Hamoukar but had to be brought in from Turkey with the nearest sources being over 70 miles away.

The discovery of an obsidian-processing center is significant, Reichel added, for it could explain the emergence of a city in this location at such an early time. A large-scale export of tools to southern Mesopotamia would have resulted in significant revenue and accumulation of wealth. “This could have been the incentive that pulled people off their fields. People specialized; instead of plowing their own fields, they bought their food supplies from surrounding villages. And once people accumulated a fortune, they wanted a walled enclosure to protect it—your first city.” Unlike in southern Mesopotamia, the move toward urbanism appears to have been influenced by economic incentive and not coerced.

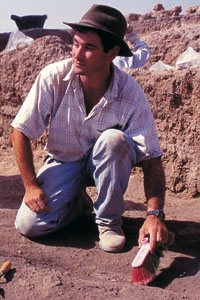

Clemens Reichel, co-director of the excavation at Hamoukar in Syria, works at uncovering some of the evidence of a fierce battle dating back to 3500 B.C. | |

The obsidian workshops were located off the main mound and predate the destroyed city by several hundred years, but numerous older levels already have been noted below the destroyed buildings in small test trenches. “We have no clear idea how far the first city at Hamoukar goes back in time,” Reichel said. “It could be much earlier than 3,500 B.C.”

By the time the city was destroyed, he added, copper had started to replace obsidian as the key raw material for tools. The discovery of numerous copper tools in the ruins of Hamoukar might indicate that Hamoukar had developed from an obsidian-processing center into one that processed copper and exported copper tools to the south.

The discovery could help lead to an additional explanation for how civilization developed in the Fertile Crescent. In the South, urban society emerged in the Uruk culture in response to the need to provide organization to an economy supported by irrigation-based agriculture.

The latest findings from Hamoukar suggest that the specialized mass-production of goods for trade could have been a similar driving force in the North.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)