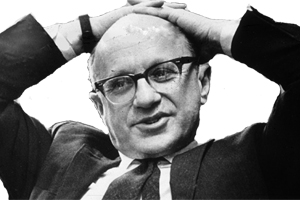

Milton Friedman, Nobel laureate, champion of free markets, dies at 94

The late Milton Friedman, the Paul Snowden Russell Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in Economics | |

The recent death of Milton Friedman produced an outpouring around the nation and the globe of remembrances and praise for his contributions to economics and government policy.

Friedman, who died Thursday, Nov. 16, in San Francisco, where he lived with his wife and fellow economist, Rose Friedman, was the Paul Snowden Russell Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in Economics.

As the premier spokesman for the monetarist school of economics, Friedman promoted the value of free market economics when the position was not at all popular.

He won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1976 for “his achievements in the field of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory, and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy.”

“He was clearly the most important economist of the 20th Century,” said Gary Becker, University Professor in Economics and the 1992 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

“He had enormous influence in economic science and indirectly on public policy. He had an important influence on President Ronald Reagan and other presidents as well as leaders in both parties through his work on the flat tax, school vouchers, flexible exchange rates, stable monetary policy and the voluntary military. He was on President Nixon’s commission to study that issue and was one of the strongest advocates for a voluntary enlistment. He had lots of good ideas and suggested practical ways to implement them.”

Becker and a group of his fellow economists from the Department of Economics and the Graduate School of Business gathered for a panel discussion at the GSB, where they offered reminiscences of Friedman as a teacher and colleague. Those faculty members who joined Becker are: Eugene Fama, the Robert R. McCormick Distinguished Service Professor of Finance in the GSB; Anil Kashyap, the Edward Eagle Brown Professor of Economics and Finance in the GSB; Robert Lucas Jr., the John Dewey Distinguished Service Professor in Economics and the College; and Sam Peltzman, the Ralph and Dorothy Keller Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of Economics in the GSB. In addition to the panel discussion, the GSB’s student-run Milton Friedman Group gathered to hear about his philosophy and to view portions of a new Friedman biography that will air nationally on PBS stations on Monday, Jan. 29, 2007.

Milton Friedman remembered in print ‘Milton Friedman, Freedom Fighter’

‘A Charismatic Economist Who Loved to Argue’

‘Milton Friedman, the Champion of Free Markets, is Dead at 94’

‘A Vision That Changed U.S.’

‘Friedman Was Right on the Money’

‘A Great Mind, Recalled’

‘Money, liberty - and lunch’

| |

James Heckman, the Henry Schultz Distinguished Service Professor in Economics and the recipient of the 2000 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, said, “Milton was one of the greatest economists of all times and certainly of the last half century. He created and fostered empirical science and made highly original contributions to statistics and economics and to human knowledge. His death was a huge loss to the world.”

As a leading advocate of monetarism, Friedman contended that changes in the money supply precede, instead of follow, changes in overall economic conditions. He pointed out, for instance, that inflation results simply from “too much money chasing too few goods.”

He was a leading opponent of John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), whose interventionist theory contended that the government should be heavily involved in managing national economies. Friedman maintained that the economy functions best when people have opportunities to make free choices unfettered by government regulations.

Friedman and his wife, Rose, were the authors of a number of influential books, including Capitalism and Freedom and Free To Choose. Free To Choose was published as a companion book to a public television series by the same name. Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and many free-market leaders in Eastern Europe were devoted followers of the Friedmans’ views.

According to their memoir Two Lucky People, published in 1998 by the University Press, the Friedmans remained devoted academics despite the unusually high public profile their work brought them. They wrote in the book, “We reflected again on the wonderful dividend from graduate teaching, of having intellectual children throughout the world É and on the emotional hold that the University of Chicago has had on those who have been there.”

Friedman came to the University to study economics after graduating with a B.A. from Rutgers University in 1932. He met Rose Friedman while both were students at Chicago, and he received an M.A. in Economics from Chicago in 1933.

A research assistant for the Social Science Research Committee at the University from 1934 to 1935, Friedman joined the University faculty in 1946, after completing a Ph.D. in Economics at Columbia University and serving as an economist with the U.S. Treasury Department and a number of other agencies.

At Chicago, he and his colleagues continued a tradition of taking the study of economics seriously by treating it as a science, and they joined other leading economists to found the Mt. Pelerin Society in Switzerland in 1947. In 1951, Friedman won the John Bates Clark Medal, which is given to economists under age 40 for outstanding achievement.

His first important work was published in the book Income from Independent Professional Practice, which he co-authored with Simon Kuznets. In the book, he contended that state licensing procedures limit entry into the medical profession and accordingly, doctors can charge higher fees than they could if competition were more open.

Throughout his career, Friedman discredited many of the Keynesian theories that were in vogue at the time Friedman began his work as a professional economist. In 1957, for instance, he published A Theory of the Consumption Function, which contested one of Keynes’ main positions: that people spend less of their income and save more as their societies become wealthier. Friedman showed that people always want more, no matter how wealthy they become. The book also showed that people’s annual consumption is a function of their expected lifetime earnings, rather than a reflection of current income, which was the Keynesian view.

In his book, Capitalism and Freedom (1962), Friedman made many recommendations that eventually became economic policies. He supported flexible exchange rates, a permanent departure from the gold standard, a volunteer army, a negative income tax, trucking and airline deregulation, competition for the Post Office and a broader-based income tax.

“Milton Friedman was a very great figure in economic science and in public life,” said Robert Lucas Jr., the John Dewey Distinguished Service Professor in Economics and the recipient of the 1995 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. “His research on monetary economics and consumer behavior earned him one of the early Nobel prizes and deeply influenced generations of economists. His tireless defense of classical economic liberalism had an enormous influence on political thinking around the world. It is hard to think of a question of economic policy in the last 50 years on which he did not make a thoughtful and valuable contribution.”

He examined the Great Depression in his book A Monetary History of the United States (1963), which he co-wrote with Anna Schwartz. Friedman and Schwartz blamed the Depression on the failure of the Federal Reserve Bank to prevent bank panics, as had been its charge when it was created in 1913.

In 1968, Friedman and economist Edmund Phelps of Columbia University conceived of what was called the “natural rate” of unemployment. Friedman pointed out that if unemployment falls below a “natural rate,” inflation follows. Government policies that promoted full employment during the 1960s and 1970s led to inflation going from 1 percent in 1960 to 13 percent in 1979.

“Milton’s impact on economics is broad and deep,” said Philip Reny, Chairman of Economics. “His contributions include important work at both the level of the individual as well as at the aggregate level of the economy. Milton’s work on the theory of individual decision-making under uncertainty and individual consumption behavior shaped the way economists think about these issues and remains important and insightful to this day. At the level of the economy, Milton’s clarity of thought as concerns monetary matters and their effects led to a revolution within the field. His ideas opened the way toward our current understanding of the connection between monetary policy, inflation and unemployment, and he can be quite accurately credited with the very successful targeted monetary policy implemented by the U.S. Federal Reserve in recent decades.”

Friedman’s work reached people outside academe in ways that few economists ever do. For example, from 1966 to 1984, he wrote a column for Newsweek magazine. The 10-part PBS series “Free to Choose,” which was broadcast in 1980, attacked welfare dependency and centrally planned economies, and it prompted a national debate about economics.

As his fame grew, Friedman was invited to advise governments around the world, including Chile and China.

More recently, he became a strong advocate of vouchers to encourage school choice.

“Milton was an intellectual entrepreneur, with an insatiable curiosity and a passion for clear thinking,” said Bob Chitester, who produced the popular PBS series “Free to Choose.” PBS will air nationally a new biography of Friedman, “The Power of Choice,” on Jan. 29, 2007.

“He set forth ideas without regard to their popularity or acceptability. He has been equally tough on himself and others in his search for tools of analysis that consistently and accurately predict outcomes in both micro- and macro-economics. And he has never compromised the resulting analysis to please those in power. Such courage is essential to the survival of a free society,” Chitester said.

Friedman is survived by his wife and colleague of many years, Rose Director Friedman; a daughter, Janet; a son, David; four grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)