Digital Darwinian world reveals architecture of evolution

By Steve KoppesNews Office

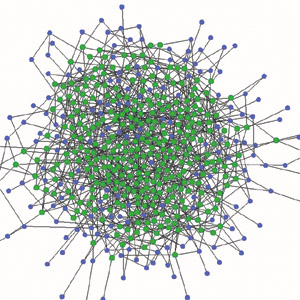

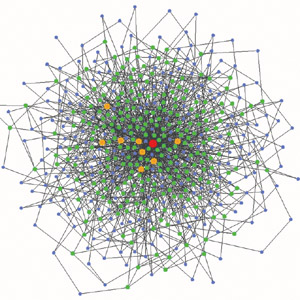

Diagram of a random network containing components that all have approximately the same number of connectivity. Computer simulations at the University of Chicago show that random networks evolve more slowly and in spurts when compared to scale-free networks.  Diagram of a scale-free network that contains components with a highly diverse level of connectivity. Some components form highly interconnected hubs, while other components have few connections, and there are many levels of interconnectivity in between. Scale-free networks are pervasive in biology. Computer simulations at the University of Chicago show that scale-free networks are able to evolve to perform new functions more rapidly than an alternative network design. | |

The architecture that pervades biological networks gives them an evolutionary edge by allowing them to evolve to perform new functions more rapidly than an alternative network design, according to computer simulations conducted at the University. The finding was published in the August issue of the journal Nature Physics.

Scientists have found the same network architecture of evolution just about everywhere they look. This architecture characterizes the interaction network of proteins in yeast, worms, fruit flies and viruses, to name a few. But this same architecture also pervades social networks and even computer networks, affecting, for example, the functioning of the World Wide Web.

“These results highlight an organizing principle that governs the evolution of complex networks and that can improve the design of engineered systems,” wrote the article’s co-authors, graduate student Panos Oikonomou and Philippe Cluzel, Assistant Professor in Physics and the College.

This organizing principle is what scientists call a “scale-free design.” A diagram of this design resembles the route maps of airline companies. “You have hubs that are highly linked with airplanes going in and out of those hubs,” Oikonomou said. But then smaller airports also exist that have far fewer connections, and there are various scales of connections in between.

Oikonomou and Cluzel initiated their project to find out if network design conferred any kind of evolutionary advantage. They created a Darwinian computer simulation to compare the evolvability of this scale-free network design with a more random design in which all network components have approximately the same number of connections. They programmed this computer world to have random mutations and natural selection operate on its digital populations, and then they compared how long it took the two types of networks to evolve the ability to perform a new task.

The populations organized in scale-free networks evolved rapidly and smoothly, while randomly organized networks evolved slowly and in spurts following a succession of rare and beneficial random events.

“They followed drastically different evolutionary paths,” Cluzel said.

Cluzel plans to conduct laboratory experiments on bacteria to test the validity of the organizing principle he and Oikonomou have identified via their simulations.

While their goal was to better understand biological evolution, social and economic networks also display a scale-free architecture. “These networks can be people, they can be molecules, they can be whatever you like,” Cluzel said.

In the engineering arena, the findings of Oikonomou and Cluzel indicate that using a scale-free architecture rather than a random network design in new electronic devices would likely produce better results.

Many engineers specialize in finding the best way to train artificial neural networks using an array of powerful computer programs. “The problem is that it usually takes time to find which connections you have to change within a network to achieve your target function,” Cluzel said.

Noted Oikonomou: “If you start with an architecture that is scale-free, maybe this would give you better results, quicker.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)