Rockefeller’s voice to return restored—with 1,500-plus new pipes

By Jennifer CarnigNews Office

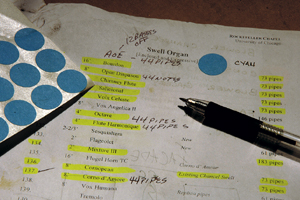

Crew members dismantle the towering E.M. Skinner Organ in Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, during a two-week removal process that took place last month. The organ, with its more than 7,000 pipes, was dismantled, sorted, labeled, packed and then shipped to the Schantz Organ Company in Ohio. There it will be restored and partially rebuilt, as the company also will add pipes that have been missing.  Thomas Weisflog, the University Organist, sits quietly and watches the process.  The movers had to identify and label all the pieces for the move, but before the labeling, pieces had to be laid out and sorted.  Rockefeller Chapel has been transformed before into a grand dining hall for the University’s Chicago Convenes events, but during the moving of the organ, its pews served as a massive work bench.  When Schantz Organ Company begins its work, the organ will be transformed as well—each pipe will be individually adjusted for tone, color and volume. | |

If music is the speech of angels, then Rockefeller Memorial Chapel has a very happy guardian angel—one that soon will get her voice back.

After years of waiting in silence, the chapel’s acclaimed E.M. Skinner organ is undergoing a $2.1 million restoration.

For two weeks in July, a crew of a dozen men and one woman descended on the chapel daily to painstakingly dismantle and remove each of the organ’s more than 7,000 pipes. The pipes, ranging from three-eighths of an inch to more than 32-feet long, as well as mechanical and electrical components of the organ, were loaded on to four tractor-trailer size trucks and then driven to the Schantz Organ Company in Orrville, Ohio. There, they will each be hand-cleaned and repaired.

During the restoration, additional pipes will be added to brighten the historic instrument’s sound, so that when the Skinner is reinstalled in late 2007, it will have more than 8,700 pipes and will be the largest organ in Chicago, said Thomas Weisflog, the University Organist.

“The sound is going to be just thunderous,” said Weisflog, who has served as Organist since Oct. 1, 2000, just three months before the Skinner was silenced. “You will literally feel the sound when it’s played. This whole place is going to vibrate.”

Installed during 1928 at the very height of Ernest Skinner’s career, the organ was originally the model of the perfect Romantic sound. But age and the elements took a harsh toll on the instrument. Constant use and accumulated grime wore it out, so in the 1970s many of the original pipes were replaced with Baroque counterparts. A chapel restoration in the 1980s successfully preserved and hardened the ceiling, but left the organ further dilapidated. And then there was water damage from a leaky roof and windows.

The result was an organ with hundreds of dead notes, pipes sticking in the “open” position and many loud air leaks. The great rush of wind made it impossible to listen to the choir sing a cappella or hear a preacher in the chancel. A rented electronic organ was finally brought in and the Skinner was retired in January 2001.

“It was just unplayable,” Weisflog said. “The only way we were able to keep music programming going here was to rent an organ because we just couldn’t keep going with what we had.”

During those years, though, most of the missing original pipes were relocated and repurchased, and former University President and ethnomusicologist Don Randel declared in a 2005 Rockefeller sermon that the organ’s restoration was a priority for him and that he would not leave the University until the funds to do so were in hand.

Later that year, Randel received a remarkable 65th birthday gift—University trustees, alumni and friends had raised $1.6 million to save and preserve the organ.

The Schantz Company earned the commission to save the instrument because its employees are known for their work on other Skinner organs, Weisflog said, including the complete restoration of the E.M. Skinner organ in Severance Hall, home of the Cleveland Orchestra.

The Rockefeller restoration process should take about a year, Weisflog said, but do not expect to hear the organ’s grand sounds before December 2007. While the organ took just two weeks to dismantle, it will take months to reassemble as each pipe must be individually adjusted for tone, color and volume. Rockefeller has a unique acoustic blueprint, Weisflog explained, meaning that the building itself informs the way the organ’s sound is heard.

Because of the 1980s work on the chapel’s ceiling, though, music fans will be in for a treat when the long process finally comes to a close. The hardening of the ceiling in the 1980s combined with the remastered and enlarged organ mean that churchgoers and audience members will hear over four seconds of reverberation when the Skinner plays.

“That’s cathedral sound,” Weisflog said. “When this is done, music in Rockefeller is going to be a new experience for everyone. Nothing like this has ever been heard in this building. It’s going to be a truly amazing experience.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)