Feldman, Scherer receive Guggenheim fellowships

By Jennifer Carnig and Steve KoppesNews Office

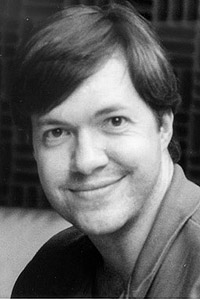

Martha Feldman | |

Two University faculty members—Martha Feldman, Professor in Music, and Norbert Scherer, Professor in Chemistry—have received 2006 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowships.

Edward Hirsch, president of the foundation, announced recently that 187 artists, scholars and scientists were selected in the 82nd annual North American competition. The awards for this year total $7,500,000 and support the research of the fellows, who are appointed on the basis of distinguished achievement in the past and exceptional promise for future accomplishment.

Martha Feldman, Professor in Music and the College and a leading music historian who works on early-modern Europe, specializing in Italy, will devote her Guggenheim fellowship and her fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies to a project titled, “The Castrato as Myth.”

“Castrati are endlessly fascinating. They combine human intervention and natural development, art and nature, and the best castrati were the most compelling singers of their time,” said Feldman. “The in-between-ness of these creatures carries immense cultural resonance, marking all kinds of developments in early modern history.”

Feldman will investigate the underlying cultural logic of the castrato in Europe, according to which the castrato first was celebrated as “a delightful wonder,” but by the turn of the 19th century became “an unnatural horror.”

According to Feldman, castrati proliferated throughout Italy and abroad, singing masses, motets, sacred concertos, cantatas and arias in chapels and courts and starring in opera seria throughout most of Europe. “Yet their condition was choked with contradictions.”

Castrati, Feldman argues, operated in a grey zone in a world that was otherwise mostly black-and-white. They were not fully male or female and symbolically they were not fully human or animal.

“Impersonating heroes and princes for monarchs, they stirred the feelings of operagoers but threatened to usurp sovereign glory,” Feldman explained. “In church, castrati mediated between God and worshipper, but the church that treasured them also forbid castration. They were objects of erotic desire, but also of fear and disgust.”

Over the period from the latter 16th century to the early 19th century, castrati swung from being adored and revered to being curiosities that were largely to be shunned.

“Shifts in his role, far from being isolated oddities on a larger cultural canvas, are taken here to index major transformations in the cultural premises and apparatus of the old regime, as it gave way to new forms of mystique focused on human integrity,” Feldman said.

Feldman also is the author of City Culture and the Madrigal at Venice (1995) and co-editor of The Courtesan’s Arts: Cross-Cultural Perspectives (2002).

The Acting Faculty Director of Contempo and the Director of Graduate Studies, Feldman joined the Music faculty in 1990. She also has served the department as Director of Undergraduate Studies and Director of Admissions.

In addition to the Guggenheim and ACLS grants, Feldman has previously earned the Dent Medal from the Royal Musical Association and the Bainton Prize for 16th-Century Studies.

Feldman earned her bachelors degree in music in 1980 and her doctoral degree in music history and theory in 1987, both from the University of Pennsylvania. Before coming to the University, she held posts at the University of Southern California and the University of Pennsylvania.

Norbert Scherer, Professor in Chemistry and the College, will devote his Guggenheim fellowship to the study of electron transfer processes in single proteins.

Norbert Scherer | |

“One of the most important chemical reactions or processes is electron, or charge, transfer,” said Scherer. “Electron transfer processes are essential for the existence and maintenance of life as we know it.”

The fellowship will enable Scherer to take a sabbatical leave during the coming academic year. During this time, he will work with researchers at the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, San Diego, and the National Institutes of Health, who have devised important theories to explain how electron transfer occurs. He also will re-immerse himself in laboratory research, a task that senior scientists who have large research groups must often leave to students and postdoctoral researchers. “As an experimental scientist, it is important to stay intimately connected with research methods, data acquisition, data analysis and modeling,” Scherer said.

Biological electron-transfer processes are central in the function of photosynthesis—the conversion of sunlight into chemical energy—and other processes by which cells and mitochondria create a variety of high-energy molecules for the function of organisms. Scherer has previously studied these processes in large ensembles of molecules on ultrafast time scales where the many molecules can be synchronized by laser excitation. Such studies provide data on the average rate of a chemical reaction. As a Guggenheim fellow, Scherer will study electron transfer in single molecules to determine the molecular motions that govern the process on biochemically important time scales.

A fellow of the American Physical Society, Scherer also has been a National Science Foundation National Young Investigator, a David and Lucile Packard Foundation fellow, an Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation Young Investigator, a Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation Teacher-Scholar, and an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation fellow.

Scherer (B.S.’82) received his Ph.D. from the California Institute of Technology before returning to Chicago in 1989 as a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow. He then served as an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania for five years. He joined the Chicago faculty in 1997.

What distinguishes the Guggenheim fellowship program from all others is the wide range in interest, age, geography and institution of those it selects, as it considers applications in 78 different fields, from the natural sciences to the creative arts.

Since 1925, the foundation has granted more than $247 million in fellowships to just over 16,000 individuals.

Scores of University scholars have received Guggenheim fellowships over the past 50 years. A list of those faculty members can be viewed at: http://www-news.uchicago.edu/resources/guggenheim.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)