Oriental Institute brings ancient Nubia to Chicago

By William HarmsNews Office

Stephen Harvey, Assistant Professor in the Oriental Institute and co-curator of the new Nubian exhibition with Bruce Williams, Research Associate in the Oriental Institute, looks over one of the display cases in the Robert F. Picken Family Nubian Gallery. The exhibition will feature 650 artifacts excavated 100 years ago in what is today Sudan, as well as photographs taken of the excavations, which will be shown in the Marshall and Doris Holleb Family Gallery of Special Exhibits. | |

Some of the world’s most significant artifacts from Nubia, an ancient African civilization that had important connections to Egypt, will go on display Saturday, Feb. 25, at the Museum of the Oriental Institute at the University.

Many of the artifacts, including one of the world’s oldest saddles, will be on display for the first time as the museum opens the Robert F. Picken Family Nubian Gallery.

Photographs taken during University expeditions 100 years ago in Nubia, now Sudan, also will be on display. The photographs show remote archaeological sites and scenes of daily life. “Lost Nubia: Photographs of Egypt and the Sudan 1905-07” will be exhibited in the Marshall and Doris Holleb Family Gallery for Special Exhibits until Sunday, May 7.

“The Oriental Institute has played a key role in the exploration of ancient Nubia,” said Gil Stein, Director of the Oriental Institute. “As early as 1905, James Henry Breasted, the founder of the institute, led two expeditions to Nubia, where he was one of the first modern researchers to document the monuments, sites and inscriptions of this ancient civilization.”

From 1960 to 1968, teams from the Oriental Institute worked intensively in the Nubian Salvage project, excavating numerous archaeological sites in both Egypt and Sudan in a race against the flooding of this part of the Nile valley, as construction of the Aswan High Dam was about to begin, said Stein.

“This long tradition of field research has given us one of the three leading collections of Nubian artifacts in the United States and gives the Oriental Institute a remarkable opportunity to present the rich heritage of Nubian civilization to the public,” Stein said. “I am also reminded by something reviewer Michael Kimmmelman wrote in the New York Times in a review of the Byzantium exhibit at the Met: ‘Most exhibits celebrate a past that we already believe. This one rewrites a past most of us barely know.’ That’s exactly how I feel about the institute’s Nubia exhibit,” said Stein.

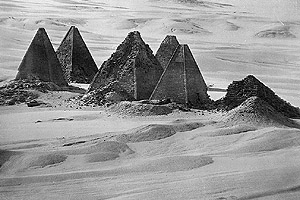

Nubian pyramids of the meroitic period (ca. 100 B.C.—A.D. 150) at Gebel Barkal. This photograph was taken by a member of the University of Chicago Expedition to Egypt and Sudan, 1906. The Nubians copied and adapted many forms of Egyptian art and architecture and built more pyramids than did the Egyptians. | |

The 650 pieces that will be on display are drawn from the 15,000 artifacts brought back from the salvage operation and represent a broad time period. “The rise of Nubian civilization presents a story of rich resources, trade and conflict with Egypt, and even the conquest of Egypt, but what also makes a dramatic impression in this gallery are the striking Nubian traditions of craftsmanship—handmade, polished ceramic vessels, carnelian and garnet beads, and elaborate wood and leatherwork,” said Geoff Emberling, Director of the Museum at the Oriental Institute.

“The Oriental Institute has the most important pieces from early Nubia outside of museums in Sudan,” said Stephen Harvey, Assistant Professor in the Oriental Institute and a co-curator of the exhibition with Bruce Williams, Research Associate in the Oriental Institute.

A large case along the south wall of the gallery contains pots, jewelry and other materials from two tombs. Among those items is an incense burner from about 3100 B.C., crafted of limestone in a circular shape typical of Nubia but decorated in Egyptian motifs. The piece has an image of a Pharaoh, a boat carrying a captive and the facade of a palace. The incense burner is a seminal piece of the heritage of the culture, Harvey said, because it shows the early influence of Egypt and how indigenous art forms were incorporated with Egyptian influences.

Nubia emerged as its own culture about the same time Egypt was developing its distinctive civilization. Much of the gold that was used by the Pharaohs to decorate their palaces and tombs came from Nubia. The Nubians also sent exotic products such as animal skins and ebony to Egypt.

“Throughout their history, the Nubians played a variety of roles with the Egyptians,” Harvey said. “They were colonized for a time and for a while were quite powerful in relationship to the Egyptians. And for 100 years, they ruled over them,” he said.

Gil Stein, Director of the Oriental Institute, surveys an exhibit case as the curators prepare for the Nubian Gallery opening on Saturday, Feb. 25. Excavated at Qustul, the incense burner (top) found in a ruler’s tomb is distinctively Nubian, though its design is similar to objects associated with early Egyptian rulers.  | |

“One of the things we want to show in the gallery is how the culture established an identity, how Nubians viewed themselves and how the Egyptians viewed them,” he said. Faces of the Nubians on sculptures and paintings show how the Egyptians portrayed their southern neighbors both as subordinated captives and as accomplished members of their society.

The Nubians were known as expert archers and horsemen. In addition to the saddle, the gallery will display a quiver and arrowheads.

Egypt and Nubia were intertwined in many ways. The Nubians built more pyramids than did the Egyptians, whose more massive stone pyramids inspired the smaller royal ones made of brick in Nubia.

Other artifacts show how the Nubians provided a bridge between the ancient Near East and Sub-Saharan Africa. A bowl from about 2000 B.C. depicting cattle, for instance, shows a respect for the value of cows to the cultures further south in eastern Africa. One of the bowls, incised with delicate designs, is one of the finest examples from the era, Harvey said.

The Egyptians made a strong presence in Nubia, constructing a famous temple to Rameses II at Abu Simbel. The temple was moved in a project overseen by the Oriental Institute when the Aswan Dam was built. The Egyptian rule of Nubia collapsed about 1100 B.C. The Nubians grew in power, and from 728 to 656 B.C., they ruled Egypt. Queens ruled during this period and the Nubians attempted to re-establish many Egyptian practices that had fallen into disuse. The Assyrians later drove the Nubians out of Egypt.

The Meroitic kingdom was established about 300 B.C. and traded with Ptolemaic and Roman rulers of Egypt. The Meroitic people wrote in a hieroglyphic script that has yet to be deciphered. Scholars know the sounds of the letters, but not their meanings. “We’ve found no Rosetta Stone for Meroitic,” Harvey said.

The museum has material from the Christian period, which began around 580 A.D. as well as the Islamic period, which started in Nubia about 1500. Among those items is one of the oldest rugs ever excavated, which dates to about 500 A.D.

The completion of the gallery also marks the conclusion of a project to redesign the Museum of the Oriental Institute, Emberling said.

“The opening of the Nubian gallery marks the end of a 10-year, $15-million project in which climate control was installed in the museum storerooms and galleries, and in which all the exhibitions were dismantled and completely reinstalled. The museum now presents the history and art of civilizations across the Middle East, from the Nile Valley to Persia, and from Anatolia to Mesopotamia.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)