Artists approach creative expression in one of two ways

By William HarmsNews Office

| |

Despite Robert Frost’s musing about the possibility of veering off toward “the road not taken,” he and other artists are, by their inclinations, pretty much destined to follow one of two major pathways to success, contends David Galenson, Professor in Economics.

Galenson, whose recent work has used economic data to examine the careers of painters, has expanded his work to study other creative artists, including poets, novelists, sculptors and movie directors. In each case, he has found that creative people fall into two camps: the conceptual artists who come up with new visions for their fields and blossom early, and the experimental artists who spend long careers polishing approaches to their work and often achieve their most important success later in life.

His findings, which challenge work by psychologists on creativity, are published in Old Masters and Young Geniuses, The Two Life Cycles of Artistic Creativity.

“What I have found provides people with new ways of understanding artists and appreciating, for instance, a trip to a museum,” Galenson said. “I also think this analysis can be used to understand how new ideas develop in many fields, including academic disciplines.”

Galenson based his findings on an examination of a number of indicators of success: the highest prices paid for art work by particular artists, listings of work in art textbooks, the number of references to particular authors in anthologies and critical opinions of the movies made by film directors. In each case, when he began to look at the age at which these creative people gained the most success, he found two different patterns at work.

“Conceptual innovators historically have been those artists most likely to be described as geniuses, as their early manifestations of brilliance and virtuosity have been taken to indicate that these individuals were born with extraordinary talents,” Galenson said. These artists are the ones who come up with entirely new approaches to their fields.

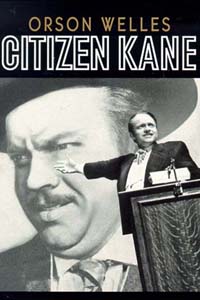

Examples of important conceptual artists are Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway and Orson Welles. The price of Picasso’s work produced in his mid-20s is much more valuable than that produced later in his career, Galenson said.

| |

“In 1943, with Hemingway just 44 years old, James Farrell called The Sun Also Rises (1926) Hemingway’s best novel and declared that his contribution was “essentially complete by age 30.” Orson Welles completed Citizen Kane, his first film, when he was 26. The film was important largely because of its technological breakthroughs.

Experimental artists, on the other hand, spend a whole career doing similar projects, seeking to find perfection. Paul Cézanne, who spent a lifetime painting similar landscapes in the south of France, reached the top of his form in his 60s, an era from which 36 percent of his paintings published in art books were produced. The share of Picasso’s works from his 60s is only 2 percent.

Frost also is a classic experimental artist. Rather than coming up with a new paradigm for poetry, as T.S. Eliot did in his famous work, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” Frost spent a lifetime listening to people in New England and reproducing the poetry of their language. Elliott was only 23 when he wrote “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” while Frost was 48 when he penned his most frequently anthologized poem, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.”

Among film directors, Alfred Hitchcock, who polished his particular form of suspense filmmaking, is a classic example of an experimental artist. Critics judge his best work to be Vertigo, which was made in 1958 when he was 59.

| |

“Experimental innovators are most often praised for their wisdom and judgment. Their major contributions typically involve superb craftsmanship, the result of painstaking effort and experience acquired over the course of long careers,” said Galenson.

By examining a wide range of data and looking at a variety of professions, Galenson was able to come up with new observations about creativity, perspectives missed by psychologists, who, for instance, study the ways in which people become innovative.

“I learned early in my career, as an economic historian, that it is important to disaggregate the components of a trend, rather than lumping all the data together and then averaging things out. I think that is the problem with the literature on creativity. People are putting all the data together and developing one bell curve, rather than separating the information on artists and finding multiple bell curves, different points at which careers peak.”

By looking at these individual trends, based on the careers of specific artists, Galenson was able to dispute some commonly held perceptions: that the field itself determines the age at which artists excel; poets peak early and novelists, late in their careers.

“The psychologists’ belief that the nature of an intellectual activity determines the pattern of the life cycle of its contributors appears to be founded on the proposition that some activities are more complex than others,” Galenson pointed out.

When artists work with abstract ideas, such as those that inspire conceptual artists, the breakthroughs can come at an early age, while other contributions, such as those that require patience and respect for tradition, take much longer and require the skills of an experimental artist.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)