Essays explore new perspectives about nature of love and erotic desire

By Jennifer CarnigNews Office

| |

Johnny Cash was not known for his philosophical insight, but when he compared being in love to falling into a “Ring of Fire,” he may have been on to something.

In Erotikon: Essays on Eros, Ancient and Modern, a new collection of articles just published by the University Press, two-dozen of the world’s leading scholars—half of whom are Chicago faculty members—take on the subject of Eros and offer their reflections on the nature, history, and power of love and erotic desire.

While contemporary Western culture tends to characterize Eros with, for example, the romantic comedies starring Meg Ryan, wedding magazines with too-perfect brides pictured on their covers and five-pound boxes of heart-shaped chocolate, these essays look at Eros across time and culture. And while there is no one conclusion, none of them looks on love as a happy experience.

“Eros is about longing and lack, it’s a desire for love that possibly cannot be filled,” said Shadi Bartsch, the Ann L. & Lawrence B. Buttenwieser Professor in Classics and co-editor of the book. “It’s depicted as a violent, unpleasant and overwhelming emotion in many ways. The abduction of Helen by Paris leads to the Trojan War, Dido is spurned and so Carthage hates Rome… This idea of love as a desire to possess has a lot of ramifications. It’s our inheritance from the classical world.”

That inheritance is explored in Erotikon through a debate on the nature of love and erotic desire led by experts in philosophy, religion, classics, film and literature, as well as artists — included in the volume are selections by poet Susan Mitchell; poet Mark Strand, the Andrew MacLeish Distinguished Service Professor in Social Thought; and author J.M. Coetzee, Distinguished Service Professor in Social Thought.

“The goal was to offer a fascinating series of ideas from a fascinating series of perspectives,” said Bartsch. “We wanted to produce a modern-day answer to Plato’s Symposium.”

Erotikon, the book, was inspired by Erotikon, the conference, a three-day event held at the University in 2001, in which a variety of scholars, many different from those published in the volume, shared their thoughts on the evolution of Eros. Both were modeled after the Symposium, Plato’s account of a gathering in Athens more than 2,400 years ago in which Eros also was explored. But while the discussion in the Symposium was sparked by a complaint that the Greek poets neglected Eros, Erotikon was organized in response to the grand role that conceptions of love have played in our imaginations since their time.

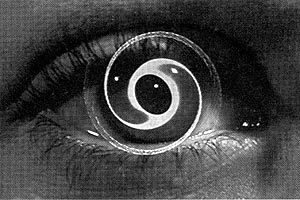

This visual from the film Vertigo, which also is found in the book, Erotikon, illustrates the feeling of dizziness, but, says Professor Thomas Gunning, it represents much more. “The circular and spiral forms of Vertigo revolve around the fullness and the fear of loss. The film figures the power of Eros precisely as ‘vertigo.’”  | |

“It’s difficult to imagine a subject more important as far as human nature goes,” said Bartsch.

A doctoral student in Social Thought and co-editor of Erotikon, Thomas Bartscherer said, “Eros won’t be ignored — it can’t be. Eros is an inescapable aspect of our individual and collective lives, something we don’t fully understand and are drawn to like moths to a flame. It’s something that constantly must be grappled with anew.” Bartscherer organized the Erotikon conference in 2001 with Katia Mitova, also a student in Social Thought.

That grappling takes place from the classical through the contemporary eras. Glenn Most, Professor in Social Thought, dissects Plato’s theory of Eros and how it must be sharply distinguished from the modern conception of “platonic love.” Plato advocates the stimulation of sexual desire as a way of escalating psychic energy, but insists that this energy must ultimately be diverted from physical expressions and toward philosophic pursuit.

David Tracy, the Andrew Thomas Greeley & Grace McNichols Greeley Distinguished Service Professor in the Divinity School, explores Augustine’s view of Eros, concluding that Augustine is a “Christian pessimist” because he maintains that there is necessarily a tragic dimension to erotic experience. Tracy proposes that this tragic vision allows us to affirm Eros while also recognizing its destructive potential.

Robert Pippin, the Evelyn Stefansson Nef Distinguished Service Professor in Social Thought, studies the erotic Nietzsche. He argues that for Nietzsche, “the problem of nihilism does not consist in a failure of knowledge or a failure of will, but a failure of desire, the flickering out of some erotic flame.”

Jonathan Lear, the John U. Nef Distinguished Service Professor in Social Thought, and Slavoj Zizek, a researcher at the University of Ljubljana, engage in a heated back-and- forth debate over Freud, Lacan and Lear’s understandings of Eros. Lear offers a re-interpretation of the Dora case and posits two kinds of psychic activity, “swerve” and “break.” Swerve is the functioning of the mind according to the pleasure principle, or its variant, the reality principle. Break is what cannot be explained by swerve — the “disruption of primary-process mental activity itself.”

Shadi Bartsch co-edited Erotikon with Tom Bartscherer. | |

Balancing these scholars are artists who evoke Eros in their work — Mitchell, Strand and Coetzee — as well as scholars who explore the idea of the erotic in other people’s work. Thomas Gunning, Professor in Art History and Chair of Cinema & Media Studies, traces the conceptions of Eros as both lack and abundance as they play out in the 20th-century Alfred Hitchcock masterpiece Vertigo.

“More than a simple evocation of the sensation of dizziness,” argues Gunning, “the circular and spiral forms of Vertigo revolve around the fullness and the fear of loss.” He further proposes that, “in a manner perhaps only the visual fascination and almost physical effect of cinema can express, the film figures the power of Eros precisely as ‘Vertigo.’”

“Films aren’t records of real life, but they do help us understand real life,” Gunning said.

In Vertigo, Jimmy Stewart plays a detective who becomes obsessed with a woman, portrayed by Kim Novak, whom he was hired to watch. Years after he sees her leap to her death, he meets another woman who reminds him so much of his lost love that he seeks to recreate her in the image of the dead woman.

“It illustrates the tragedy of love, the inability to deal with love even when you get it, even when it returns to you from the land of the dead,” Gunning explained. “Is marriage the continuation of Eros or is it the end of it? The error of thinking is that fulfillment is always boring, and so once we get something, we don’t want it anymore. Desire can’t be desire if you have what you wanted.”

His conclusion both on the film and beyond is that Eros really is like a fire.

“If love doesn’t risk being self-destructive, if it doesn’t burn, I’m not sure it’s love,” he said.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)