CAMEL allows archaeologists to survey ancient cities without digging in the dirt, disturbing sites

By William HarmsNews Office

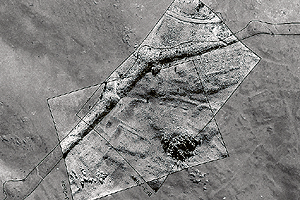

Overlying aerial photographs show the ancient city wall at Kerkenes Dag in Turkey. | |

Like a dromedary that can travel a long distance without taking a drink of water, the Oriental Institute’s CAMEL computer project can traverse vast distances of ancient and modern space without pausing for the usual refreshment known best by archaeologists—digging in the soil.

CAMEL (the Center for Ancient Middle Eastern Landscapes) is at the leading edge of archaeology because of what it does not do and what it can do. First, it does not actually excavate. For a science based on the destructive removal of buried artifacts and an examination of them for meaning, CAMEL works in quite the opposite way: it aims to survey ancient sites and disturb them as little as possible.

What CAMEL can do however, is remarkable. It organizes maps, aerial photography, satellite images and other data into one place, allowing archaeologists to see how ancient trade routes developed and to prepare simulations of how people may have interacted, given the limitations of their space, the availability of resources and the organization of their cities.

CAMEL provides the wonderful opportunity “to see beyond the horizon,” said Scott Branting, Director of the project.

Branting oversees the CAMEL project from a second-floor computer lab at the Oriental Institute. As he walks around, he shows off the dozen PCs that form the nucleus of the project, which invites faculty and students to pore through electronic images from throughout the Middle East.

“;“The Near Eastern area is defined for the purposes of our collections as an enormous box stretching from Greece on the west to Afghanistan on the east, from the middle of the Black Sea on the north to the horn of Africa on the south,” he said as he turned on a computer to summon an image from the area.

Up popped an aerial surveillance photograph taken for defense purposes during the Cold War. The image showed mounds on the surface of the steppe regions of modern Iraq, sites that are among the hundreds unexplored there that are potentially valuable sites for future excavation when archaeologists can safely return.

“Because these images are images from the 1950s and 1960s, they show a terrain much different from what exists today,” he explained. Fields have covered much of the formally barren areas of the Middle East as irrigation has expanded farming. Sites that show up as mounds in photographs may today be leveled and hard to recognize. Some of the ancient material they contain, however, is still buried deep below the surface.

Besides the aerial surveillance photographs, the collection includes some photographs taken by small planes in the early days of aerial photography.

James Henry Breasted, founder of the Oriental Institute, was an early pioneer in the field and began taking photographs from a plane over sites in Egypt in 1920. Some of his early shots are a bit shaky, though, as he also experienced air sickness during that path-breaking effort.

When the Oriental Institute launched an excavation in the 1930s at Persepolis in Iran, the art of aerial photography had progressed greatly, and stunning pictures of the ancient Persian capital helped demonstrate the scope of the city in a way nothing else could. Some of those photographs are on the walls of the Persian Gallery of the Museum of the Oriental Institute, and others are part of the CAMEL database.

Oriental Institute scholars also used balloons rigged with cameras to catch overall shots of excavation sites.

In addition to the aerial photographs, the collection also includes shots taken by NASA, Digital Globe and other organizations from satellites.

Branting is in Turkey this summer working on a site that shows the value of nondestructive techniques such as those developed at CAMEL. He has been studying the ancient and mysterious city of Kerkenes Dag in central Turkey.

The city, surrounded by a wall, is a square mile, huge by ancient standards, and is the largest preclassical site in Anatolia, the name for the ancient region that now includes Turkey. The city is about 30 miles from Hattusa, the capital of the ancient Hittite Empire.

Although the city was an Iron Age site and was planned and built by powerful leaders capable of controlling a large work force, it is uncertain who held that power. Early scholars had speculated it may have been a rival to the Hittites, but a research team from the Oriental Institute established in 1928 that the city was built sometime after the fall of the Hittites in about 1180 B.C.

Geoffrey Summers of the Middle East Technical University in Ankara directed a new dig at the site beginning in 1993. Branting joined the project in 1995 as an Oriental Institute graduate student. Researchers from the Middle East Technical University and the Oriental Institute then joined efforts to work on the project together.

From the beginning of the latest work at Kerkenes Dag, archaeologists have used nondestructive techniques to learn more about the site. Random trench work would probably not turn up much more information than was recovered in the 1928 Oriental Institute excavation, scholars have contended.

“By employing a range of observational and remote sensing techniques across the entire area of the city, we have been able to fill in the blank spaces on an earlier map made by the Oriental Institute,” Branting said. The work, which includes the techniques used at CAMEL to map accurately a site with photographs, provided archaeologists a chance to work with a high degree of precision once digging began. Currently, another season of excavation is underway.

“Since so much can be seen on the surface at Kerkenes Dag, this has proved to be a very effective technique,” Branting said.

Global Positioning System technology has allowed scholars to record the minute topography of the entire ground surface within the site. “Never before in archaeology has this technique been undertaken on such a grand scale. The terrain model is the basis for ongoing work to produce a virtual reconstruction of the entire city, neighborhood by neighborhood, building by building,” he said.

By using the techniques, the team was able to locate the gateway of the palace complex and find the first fragmentary inscriptions and reliefs to be recovered at the site. They have been able to date the site to the mid- to late-seventh century through the mid-sixth century B.C.

Scholars believe the city may have been one referred to by Herodotus as Pteria, which was conquered by the Lydian King Croesus in a failed effort to block the advance of the Persian Empire.

“If the equation of Kerkenes Dag with Pteria holds true, then we can even more precisely date the massive destruction of the city to around 547 B.C. and begin to understand something of its international importance,” Branting said.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)