‘Migrating to the Movies:’ Stewart’s new book shows how early cinema helped create black history

By Jennifer CarnigNews Office

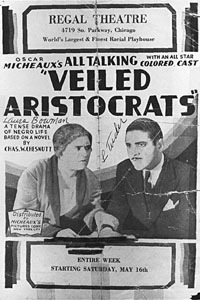

Jacqueline Stewart  The film stills shown here feature two “race films,” black-cast films made before 1950 for segregated African-American theater patrons. Above is a still from Spencer Williams’ 1946 movie The Girl in Room 20 (63m).  Above, the 1939 film Harlem Rides the Range (56m), directed by Richard Kahn, is featured.  A poster advertises the Oscar Micheaux film of 1932, Veiled Aristocrats (44m). These films and others like them were independent productions that provided black viewers with images of African-American experience that were conspicuously absent from Hollywood films, including black romance, urban migration, social upheaval and racial violence. | |

The Great Migration and the rise of cinema both changed the American cultural landscape, and yet rarely have these two simultaneous developments been studied together. In Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Urban Modernity, Jacqueline Stewart provides the first thorough study of African Americans and early film, and she concludes that the first major waves of black northern migration not only reorganized America’s social relations but also its media institutions.

Black film culture was more than an alternative to or protest against dominant cinema, Stewart argues. It was actually part of the development of a dominant white film culture. “The ways in which blackness emerges and is suppressed in their films ... suggests how deeply the cinema was affected by the country’s shifting racial patterns,” writes Stewart, Associate Professor in English Language & Literature and the College, and a member of the committees on Cinema & Media Studies and African & African-American Studies.

“If we read the making of black film culture as a migration narrative, an important part of the story is how migrations of blackness into the dominant cinematic imagination reflected and affected larger black efforts to move out of traditional, restricted roles.”

Having studied black images in film, black spectatorship and early black filmmaking, Stewart concludes in Migrating to the Movies that white image-makers always have been anxious about what to do with black subjects. But instead of writing off early films as simply “racist,” she recovers a strength and influence that she says black moviegoers really had. Whether it was by creating a sense of community in all-black theaters, by boycotting offensive movies, or by financing and creating movies that dealt with issues of importance to some in the community, African Americans successfully intervened in racist patterns of the dominant culture, Stewart argues.

“My goal was to produce a more complicated, more accurate picture of how African Americans engaged with an institution as powerful and seemingly monolithic as the dominant film industry,” Stewart says.

According to Henry Louis Gates Jr., the chair of Harvard University’s department of African and African-American studies, Stewart accomplished her goal.

“As a child in West Virginia, I loved the movies, but I had little idea that my people’s history was being constructed (and deconstructed) as I watched them,” Gates says. “Stewart’s bold new book lets us see how black history was, in part, made at the movies. The history of the Great Migration has rarely been so vivid or compelling.”

Migrating to the Movies began as Stewart’s dissertation—she earned her A.M. in 1993 and her Ph.D. in 1999, both at the University—and although it was developed and written here, its connections to Chicago are far greater. The book is as much a history of Chicago’s South Side as it is a history of the Great Migration and the nation’s fledgling film trade.

“The South Side of Chicago is a very important and under-acknowledged film site,” says Stewart, who was born and raised here (she graduated from Kenwood Academy High School in 1987). “I wanted to help keep Chicago on the map of American film history.”

Though today it is routinely cut off of tourist maps of the city, the South Side was once the hub of a successful movie industry. Home to at least 18 African-American theaters with names such as the Pekin and the Vendome and numerous black-owned film companies, the South Side is where vaudeville promoter and theatrical agent William Foster produced The Railroad Porter in 1913, the first ever black-produced film.

And it was in Chicago where Oscar Micheaux created many of his more than 40 films that dealt with such controversial subjects as lynching, the Ku Klux Klan and Southern racism. Though she draws stylistic and political comparisons to Spike Lee, Stewart describes Micheaux as “the most prolific black feature filmmaker ever.”

To study the black moviegoing culture of that time in Chicago, to which her own grandparents migrated, Stewart spent more than a decade watching silent films and reading turn-of-the-century African-American newspapers, such as the Chicago Defender. She then knit together a history of the many black theaters and film companies that flourished along the “Stroll”—black Chicago’s primary commercial and entertainment strip along south State Street—with newspaper and literary accounts of what it was like for some African Americans to go to the movies.

“By developing public spheres like the black press, race theaters and race movies, African Americans intervened in the racist patterns of dominant cinema,” Stewart writes, explaining how African Americans approached moviegoing, just as they developed strategies for addressing racism in other arenas of public life.

“If the book only makes one contribution, I hope that it paints a more nuanced picture of how a marginalized group dealt with the dominant culture,” Stewart says. “What I tried to recover is the power and authority that the black moviegoer really could have.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)