University space probe instrument records particle hits near Enceladus

By Steve KoppesNews Office

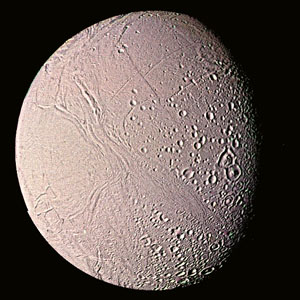

A University-built instrument on the Cassini space probe is encountering dust particles around Enceladus, an ice-covered moon of Saturn (shown above) during the space probe’s flybys on the plane of Saturn’s E-ring. | |

An instrument designed and built at the University for the Cassini space probe has discovered dust particles around Enceladus, an ice-covered moon of Saturn with the distinction of being the most reflective object in the solar system. The particles could indicate the existence of a dust cloud around Enceladus, or they may have originated from Saturn’s largest ring, the E-ring.

“We are operating on the plane of the E-ring, and things are very complicated there,” said Thanasis Economou, a Senior Scientist at the University’s Enrico Fermi Institute who monitors the performance of the instrument. “It will take a few more flybys” to determine the origin of Enceladus’ dust cloud, Economou added.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration launched Cassini, an international mission involving 17 nations, in October 1997. Last July, after a journey of 2.2 billion miles, Cassini became the first spacecraft to orbit Saturn.

The discovery is the first for the Chicago instrument, called the High Rate Detector. “During all this time from Earth to Saturn, we didn’t have any real test of the instrument. I was very happy to see that the instrument performs well after so many years,” Economou said.

Cassini encountered Enceladus at an altitude of 733 miles on Thursday, Feb. 17. On that date, the Chicago instrument recorded thousands of particle hits during a period of 37 and a half minutes. Cassini executed another flyby of Enceladus on Wednesday, March 9, at an altitude of 311 miles. “Again we observed a high stream of dust particles. Again it looks like the stream is coming from Enceladus,” Economou said.

The largest particles detected by the Chicago instrument measure no more than the diameter of a human hair—too small to pose any danger to Cassini. “Our measurements are important to evaluate any risk to the spacecraft,” Economou said.

The High Rate Detector is part of a larger instrument, the Cosmic Dust Analyzer, which with further analysis may be able to determine whether the particles are made of ice or dust. Enceladus measures 310 miles in diameter and reflects nearly 100 percent of the light that hits its ice-covered surface.

“If you look at the surface on Enceladus, it’s very smooth,” Economou said. Scientists have speculated that Enceladus is the source of Saturn’s E-ring, the planet’s widest, stretching 188,000 miles. It is possible, the scientists said, that gravitational interactions between Enceladus and another moon of Saturn have triggered some form of water volcanism.

“The High Rate Detector measurements are extremely important in order to understand the role of Enceladus as the source of the water ice particles in the E-ring,” said Ralf Srama of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics, who heads the Cosmic Dust Analyzer science team. This study requires precise measurements of dust density in the Enceladus region, “but without the High Rate Detector this would not be possible,” Srama said.

Enceladus orbits Saturn at a distance of approximately 147,500 miles, almost two-thirds the distance from Earth to the moon. Additional Cassini encounters with Enceladus are scheduled to occur Thursday, July 14, 2005, and March 12, 2008.

Anthony Tuzzolino, Senior Scientist in the Enrico Fermi Institute, created the High Rate Detector under the direction of the late John Simpson, the Arthur Holly Compton Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in Physics. The instrument was designed to collect data on Saturn’s rings and is capable of counting up to 100,000 impacts per second.

Cassini carries a total of 12 primary instruments that often must compete with one another so that the orbiter is properly oriented for collecting data. “We did our best in order to make this happen, and the preparations and negotiations for these encounters were enormous,” Srama said. “These were perfect flybys, and we did everything possible.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)