Digital reconstruction could resurrect original vision of many ancient artists, craftsmen

By Jennifer CarnigNews Office

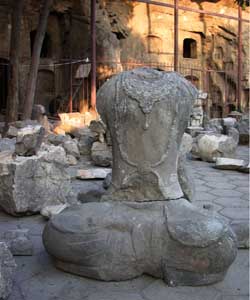

The Xiangtangshan Caves, a collection of a dozen sixth-century Buddhist cave temples south of Beijing, were once full of immaculate altars. The photo above shows what remains after looters left many of the statues and carved figures on the walls without faces or heads.  In a courtyard outside the cave sits a headless bodhisattva. | |

It is a familiar story: Whether the location is a pyramid in Egypt, a museum in Iraq or a Native American burial ground in Montana, looters, art lovers or any combination of the two have stripped the sites bare of their artifacts, leaving little for scholars to study and a gap in what can be learned about a particular group of people in a particular period of time. Fragments of history are carted away, often taken thousands of miles from their place of origin, never to be returned.

In the hopes of addressing this problem, a new University project, which the Center for the Art of East Asia is launching, may provide a model for how to best deal with the looting and dispersal of art and artifacts. The model is the Xiangtangshan Caves Project: Reconstruction and Recontextualization. The project will bring together scholars from the United States and China with the latest technological developments in three-dimensional imaging to create a multi-dimensional, digital reconstruction of Buddhist cave temples that have been ravaged by looters.

“This project has global ramifications,” said project leader Wu Hung, the Harrie H. Vanderstappen Distinguished Service Professor in Art History and the Director of the Center for the Art of East Asia. “As academics, it’s our responsibility to find an answer to this vexing problem and provide a positive model of how to deal with this issue. I think we may just have found the solution we’ve been looking for.”

If it goes as expected, the project—which the center is creating in collaboration with the Smart Museum of Art and Lec Maj, a Computer Research Assistant for Humanities and Networking Services and Information Technologies—could become a template for how archaeologists, art historians and museum directors can deal with issues of stolen cultural artifacts, be it in China, Zimbabwe or Illinois.

The Xiangtangshan Caves, a collection of a dozen sixth-century Buddhist cave temples south of Beijing, were once full of immaculate altars—limestone sculptures of the Buddha with attendant figures were carved from the solid rock, brightly painted flying divinities and floral scrolls were carved in relief on the rock walls and, below, crouching monsters were depicted lurking in the shadows.

But today the caves are in a state of extreme disrepair. Early in the 20th century the quality of the caves’ sculptures attracted the attention of art dealers and collectors, so many of the images and sculptural fragments were forcibly removed, sold on the art market and scattered around the world. Many of the missing sculptures have been outside of China for nearly a century, so the caves have never been photographed intact.

Enter Wu and an international team of 10 members, including scholars from the fields of archaeology, art and architectural history, museum curators, and a technical advisor. The team is planning to use the latest in laser scanning technology to create virtual, 3-D renderings of the caves to simulate the original appearance of the rock-cut shrines.

Project coordinator Katherine Tsiang Mino, Associate Director of the Center for the Art of East Asia, spent years as an Art History student at Chicago, tracking down the caves’ missing sculptures for her dissertation. She has located many of the caves’ original pieces, and those sculptures now will be scanned and turned into 3-D images. Next, digital pictures will be taken of the caves themselves. The team will then put together a giant, real-life puzzle using highly specialized computer programs and their research on the cave temples to fit all of the sculptural fragments back into their original positions.

The final product will be a 3-D digital rendering of the Xiangtangshan temples that can be projected into simulated caves to show how they once looked. Visitors and scholars could then have the remarkable opportunity to study the caves as they were in the sixth century. The digital reconstruction also could be used to bring the caves to audiences all over the world. Those who cannot travel to China might still have the experience of exploring one of the caves in an exhibition gallery, classroom or history museum.

“This is a historic project,” said Mino. “We’re going to be able to construct a more complete picture of the culture, the social environment and the political landscape of the time.”

In addition to its broader implications, the project will also provide a better understanding of the cave temples of Xiangtangshan (“Mountain of Resounding Halls”) and of the art and visual culture of the Northern Qi period (555-577). The art of this brief dynastic period is characterized by startling innovation and high quality artistic production, of which these caves are arguably the major existing monuments, Mino explained.

The Northern Qi dynasty was ruled by non-Han Chinese Xianbei people who took over northern China in the fourth century. During their rule, foreign contacts increased—Buddhist monks came from India and Central Asia, and merchants arrived from points along the Silk Road with goods to trade.

“It’s a fascinating and important period that needs to be reassessed,” Wu said, explaining that foreign influence on China has been understudied. The intercultural qualities of the art in the Xiangtangshan caves can provide valuable information about the cultural, religious, social and political life of the time, he added.

Mino also pointed out that the scanning process is especially important in this case because coal mining is prevalent in the southern Hebei province where the caves are located. The acid rain and dust from the mines and cement factories are causing the art in the caves to deteriorate at a rapid rate. In the 10 years that Mino has been going there to conduct research, she has noticed firsthand the remarkable rate of decline. “This is a way, which is in our control, to preserve the caves,” she said.

The Xiangtangshan Caves Project will begin this summer with digital scanning and continue into 2006. An exhibition is planned for 2008 at the Smart Museum of Art in which the exhibition hall will be transformed into one of the caves with the help of the 3-D digital images.

The multi-dimensional show will present both the virtual reconstruction of the caves and actual examples of art that has been removed from the caves. An international conference to be held at the University also is being planned for 2008, which will present research from a range of fields on the Northern Qi period and share ideas and methodologies for further study. The conference papers will then be collected for a scholarly volume for publication.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)