Astronomers interpret Hubble images in same majestic light as early painters of America’s western landscapes

By Jennifer CarnigNews Office

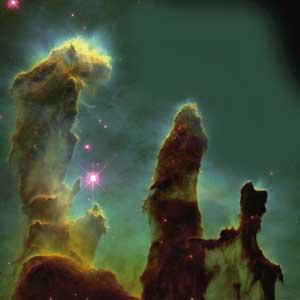

Elizabeth Kessler, a doctoral student in the Committee on the History of Culture (above), describes her research, which compares the images that astronomers of the Hubble Heritage Project manipulate when they add color to the photographed gases in space, with paintings of American West landscapes. “With its yellowish pillars, the Hubble Space Telescope’s Eagle Nebula (directly below) could almost be a detail from Thomas Moran’s sublime Western landscape painting (below), Cliffs of the Upper Colorado River, Wyoming Territory, 1882. The orientation of the nebula is a largely arbitrary choice, but one that encourages the analogy with the earthly landscape. The choice also gives the gaseous pillars a sense of monumentality as viewers eyes are drawn upward to their brightly lit tops. The similarity then rests not only on the resemblance of the forms, but also the tradition of representing nature as awe-inspiring and majestic.”   | |

Although derived from scientific data, the spectacular images from the Hubble Space Telescope circulate far beyond the scientific community. From postage stamps to the cover of a Pearl Jam CD, images of the heavens collected by Hubble have become part of American culture, appreciated not only for their scientific content, but also for their raw emotional power.

It is that powerful ability to move the viewer that art historian Elizabeth Kessler is studying in her dissertation. Kessler, a doctoral student in the Committee on the History of Culture, presented some of her research at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science last month, an honor typically reserved for scientists who already have earned their Ph.D.s.

Kessler joined faculty members from the University of California, Irvine, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as staff from the National Air and Space Museum and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, as they presented their work Friday, Feb. 18, in Washington, D.C., on “The Significance of the Hubble Space Telescope: Space Science Past, Present and Future.”

Kessler, whose background is planted firmly in the humanities (she received her M.A. in art history from the University of Illinois and her B.A. in English from the University of Notre Dame), presented “Hubble’s Vision: Imaging, Aesthetics and Public Reception.” She brought a unique perspective to the scientific conference, and she maintains it is necessary to consider aesthetics in science, especially if one is to fully understand the space telescope and its impact.

“There’s a lot of translation that occurs between the data the Hubble collects and the final images that are shared with the public,” Kessler says. Translating raw data into the “pretty pictures” that have become a staple of newspaper front pages requires careful image processing. Astronomers and image specialists strive for realistic representations of the cosmos, yet they make subjective choices regarding contrast, composition and color.

The Hubble images are complex representations of the cosmos that balance both art and science. In that sense, as well as in their appearance and emotional impact, Kessler says, they resemble 19th-century Romantic landscape paintings, especially those of the American West.

“The aesthetic choices made result in a sense of majesty and wonder about nature and how spectacular it can be, just as the paintings of the American West did,” Kessler says. “The Hubble images are part of the Romantic landscape tradition—they fit that popular, familiar model of what the natural world should look like.”

Kessler explains that the raw data the Hubble transmits are black-and-white electronic pictures that show little definition or detail. To get from those unintelligible images to breathtaking magazine covers, astronomers take three raw Hubble filters—each filter records a different wavelength of light—combine them and then interpret their meaning, applying color to each filtered image, removing streaks and cropping it so it becomes a standard four-sided image.

Getting to the final photo, then, is a careful balancing act of combining scientifically relevant information with the desire for an attractive image that captures attention. As scientifically based as the photos are, there is a wide range of possible interpretations for each image.

The interpretation often chosen, Kessler says, is one that suggests buttes, cliffs and erosion. Some look strikingly like pictures from Yellowstone National Park, or paintings of the old West by Albert Bierstadt or Thomas Moran, placing the Hubble images solidly in the romantic landscape tradition.

“Just like Bierstadt’s or Moran’s paintings, the hope here is that the final image will capture the feeling of awe and majesty and wonder about nature,” Kessler says.

The goal in creating these images is as much about sparking an interest in science as it is about educating. “Scientists really want some kid to have a poster of this on a wall, as they did pictures of the moon. They want science to invoke a sense of frontier and discovery.”

Kessler’s work is more than just conjecture. She spent months interviewing members of the Hubble Heritage Project, the astronomers who create the popular space telescope pictures. She also has worked closely with the scientific community.

Last year, she earned a Guggenheim Fellowship to study at the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institute. While there, she worked with David DeVorkin, one of the museum’s curators and the moderator of the AAAS panel on which she spoke.

“While I am generally skeptical of different approaches,” says DeVorkin, “I welcome them.” He supports Kessler’s research. “She’s done something that a lot of people have tried to do but have never been able to convince me is worthwhile,” DeVorkin says. “She actually is on to something. She looks at how aesthetics enter into what is obviously an effort to persuade. Just like 19th-century artists accompanied Western exhibitions to persuade people about the greatness of the West, these space telescope images are doing that for space. She’s been able to link the two better than anybody else. I’m very excited about her work.”

DeVorkin invited Kessler to work on a book, The Hubble Space Telescope: Imaging the Universe (2004), which he was writing for National Geographic with acclaimed science historian Robert Smith. “Beth’s chapter was excellent,” DeVorkin says. “She contributed significantly to the book.”

DeVorkin says he invited Kessler to present at the AAAS meeting because she uses explanatory tools in her discipline to better illuminate phenomena in a completely different discipline.

“This is a meeting of scientists,” DeVorkin says, and he believes Kessler’s presentation was well received. “That’s about the top compliment I can give,” he adds.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)