Scholars to examine language, power it gains in evolution from spoken to written

By William HarmsNews Office

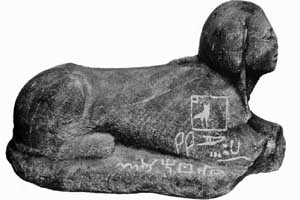

Among the earliest alphabetic writing in the world is the graffiti (above) on a sphinx from the turquoise mines of Serabit in Egypt. | |

The Oriental Institute is organizing a conference, “Margins of Writing, Origins of Cultures: Unofficial Writing in the Ancient Near East and Beyond,” to be held in Breasted Hall Friday, Feb. 25, and Saturday, Feb. 26.

The first of its type, the conference will bring together linguists, anthropologists and scholars of the ancient Near East to discuss the latest results of research on the history of politics and writing, said conference organizer Seth Sanders, a postdoctoral scholar at the institute.

The scholars will look at the rise of language varieties from mere “dialects” to the enduring symbols of whole cultures, from the birth of Babylonian and the death of Sumerian, to the creation of the Hebrew Bible’s language. Those changes are fundamental to understanding how history is made, Sanders said.

“This conference is important because it brings together specialists from the social sciences and the humanities to examine the political power that a language takes on once it assumes a written form,” said Gil Stein, Director of the Oriental Institute.

“Everything changes when a spoken language develops a script. All of a sudden it can be used by the central authorities of a state as a technology of social control. At the same time, it can become an important tool of resistance to the power of the state. It’s fascinating and important to understand this very dynamic and contested relationship between politics and language because it can provide us with unexpected insights into the ways that societies develop and change,” Stein said.

Sanders pointed to a modern and an ancient example of how language can be both a tool of dominance and resistance to authority.

In the early 20th century, when Turkey was trying to make a transition from being a traditional Islamic country to being a modern nation, the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Ataturk, decided he needed to create a new national identity to move the country away from Islamic tradition and the power of the imams. So he changed the script in which the Turkish language was written from Arabic to a new western looking alphabet. “Suddenly the imams, who had power over tradition because of their literacy in Arabic, became illiterate. Now in order to be literate, you had to study in Turkish schools and learn the new Turkish culture,” Sanders said.

The Hebrew Bible also was probably written to break away from the dominance of a powerful culture and to create a new national identity, he said. “When the Bible was written, the great empire was Assyria, and everyone had to use Assyria’s language to communicate internationally. So the Israelites wrote down a version of the language they were speaking and used it to record events from their point of view. Even though they lost politically in the short term, their writing perpetuated their point of view with power nobody could have imagined. Even today, people claim to be ruled by the laws of the Bible,” he said.

William Schniedewind, chairman of near eastern languages & cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles, will discuss the life, death and new life of Hebrew in his talk titled “Aramaic, the Death of Written Hebrew, and the Rise of Linguistic Nationalism in the Persian and Hellenistic Periods.”

Theo van den Hout, Professor in the Oriental Institute, will examine the Hittite empire to determine if a similar situation occurred when rulers wrote their language in Babylonian-style cuneiform while a popular language written in hieroglyphs and known as Luwian developed simultaneously. His talk is titled “Institutions, Vernaculars, Publics: The Case of Second Millennium Anatolia.”

Other University speakers at the conference will be John Kelly, Professor in Anthropology, who will present “Writing and the State: China, India and General Definitions;” Sanders, who will present “The Encounter Between Writing and Language in the Ancient Near East;” and Christopher Woods, Assistant Professor in Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations, who will speak on “Bilingualism, Scribal Learning and the Death of Sumerian.”

Also participating in the conference will be Michael Silverstein, the Charles F. Grey Distinguished Service Professor in Anthropology, and Sheldon Pollock, the George V. Bobrinskoy Distinguished Service Professor in South Asian Languages & Literatures.

Sessions will be held Friday, Feb. 25, from 9:15 a.m. to 12:15 p.m. and from 1:15 to 4:15 p.m. On Saturday, Feb. 26, sessions will be held from 9:15 a.m. to 12:15 p.m. The final response and roundtable will take place from 1:15 to 3:15 p.m.

Full conference details may be found at http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/IS/OIS/MARGINS_2005/Margins_2005.html.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)