Wagner wins Schuchert Award for promising paleontology research

By Steve KoppesNews Office

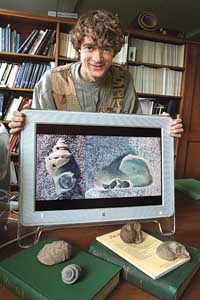

Peter Wagner displays some of the fossil samples he studies. | |

Peter Wagner’s research on the twists and turns of fossil snail shells and evolutionary theory has earned him the Paleontological Society’s 2004 Charles Schuchert Award, bestowed annually on a scientist under 40 whose work reflects excellence and promise in paleontology.

A Lecturer in the Committee on Evolutionary Biology and associate curator of geology at the Field Museum, Wagner received the award in November at the society’s annual meeting in Denver. He is the 10th University faculty member or alumnus in the Geophysical Sciences Department to receive the award since it was established in 1973.

Wagner (Ph.D.,’95) studied under the late Jack Sepkoski, a former Professor in Geophysical Sciences and Organismal Biology & Anatomy, and the 1983 Schuchert Award winner. Last year’s recipient was Steven Holland (Ph.D.,’90), now a geology professor at the University of Georgia.

Wagner studies big evolutionary questions primarily through the statistical examination of anatomical changes in fossil snails that lived during the Paleozoic Era, which preceded the Age of the Dinosaurs. “They might seem like mundane animals, but in truth they have a phenomenal range of variation,” Wagner said.

This variation serves as a convenient testing ground for studying the rates at which their anatomy evolves.

“A lot of evolutionary theory makes predictions about when rates should speed up or slow down, that some features should evolve at a faster rate than others, and that there might be situations where particular groups of organisms will show higher rates than will others,” he said.

Wagner currently is analyzing snails that lived during the Devonian Period, approximately 400 million years ago. During the Devonian, jawed fishes and other major predators rapidly began to diversify. Because these animals had jaws that could crush snail shells, scientists would expect to see the shells evolve rapidly in response.

“Snails are a much sought-after food item. They’re one of the few things from the Paleozoic that if you were to see it served today, it would be in the least bit appetizing,” he said.

In fact, Wagner’s analysis indicates that spines and other shell-reinforcing characteristics did appear at increased rates during the Devonian. Still other features associated with weaker shells already were disappearing, but started to fade out even more rapidly.

“I would suggest that as some people had predicted, the rates of anatomical evolution changed in the Devonian,” said Wagner. “It doesn’t prove that it was the fault of the fish or other predators, but it’s a nice smoking gun.”

David Jablonski, the William Kenan Jr. Professor in Geophysical Sciences, nominated Wagner for the Schuchert Award.

“What’s extraordinary about Pete Wagner’s work is his very creative approach to asking questions about how the fossil record can inform us about evolution, using methods that are really quite new to the paleontological field,” said Jablonski, the 1988 Schuchert Award recipient.

“He’s also been one of the leaders in asking how the data of the geological record—the sequence of fossils, warts and all, including the gaps seen over geologic time—should be integrated into our reconstructions of evolutionary relationships.”

Wagner weighs rival evolutionary hypotheses against one another using a method called the maximum likelihood approach. “It’s really impressive,” Jablonski said. “It’s a much more sophisticated set of statistical tools than have generally been applied to testing hypotheses in the fossil record.”

Wagner spent three weeks collecting fossils in the Australian outback earlier this year, but most of his research takes place in museums. “Paleozoic snails simply have not received a lot of attention. People have been collecting them for 200 years and mostly letting them pile up,” he said. Wagner likened it to playing with “the last century’s worth of Christmas presents.”

He also actively participates in the Paleobiology Database, a multidimensional, Web-based catalogue of plant and animal fossils of all ages from around the world that paleontologists draw upon for their research, and he has been a member of the database’s advisory board since its inception. Based at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis in Santa Barbara, Calif., the database was initiated by two Chicago alumni, John Alroy (Ph.D.,’94) and Charles Marshall (Ph.D.,’89).

At the University, Wagner teaches a course every other year on the history of life for undergraduate students. He also has taught an informal course on likelihood theory, a branch of statistics, for graduate students.

“He’s been a wonderful colleague as a sounding board, as a source of ideas and advice for graduate students and faculty alike,” Jablonski said.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)