‘Kanji alive’ aids language learning

By Jennifer CarnigNews Office

| |

When students need to know three writing systems just to read a Japanese newspaper, it is no surprise to hear they have a tough time learning the language. But a new computer program available online and created at the University is making it easier for students worldwide to master kanji, the language’s complex characters.

Harumi Lory, Senior Lecturer in East Asian Languages & Civilizations, led the team that designed the program “Kanji alive.” Unlike any other Japanese learning tool, “Kanji alive” allows students to customize at-home exercises to meet their learning needs.

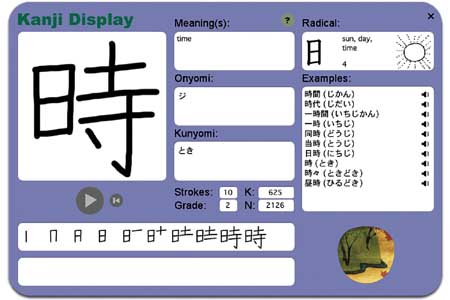

On one of its Web pages, users can watch a kanji being drawn stroke by stroke, hear it spoken by a native speaker and see it spelled phonetically using other characters. Users can see how a particular kanji is used in compounds and even watch an animated etymology of its radical. Image, sound, theory and history are combined in an online program that has changed the way beginning and intermediate Japanese is taught at the University.

“Kanji are very difficult to learn,” Lory explained. “Every small dot or line has a meaning, so they’re difficult to learn to write. And then, many kanji have lots of different readings, so they’re difficult for students to remember. Kanji are very tricky for non-native speakers.”

A central challenge for English-speaking students of Japanese is, not surprisingly, the character-based system of Japanese writing. Japanese characters come in three types: two forms that are used phonetically and are similar to the Roman alphabet, and a third, kanji, which is derived from Chinese.

Chinese characters, along with Chinese culture, came to Japan in the fourth or fifth century, at a time when the Japanese language still had no writing system. The Japanese people first adopted Chinese characters to represent the sounds of their spoken language, regardless of a character’s Chinese definition. Later, this approach was reversed—Chinese characters were used ideographically, regardless of their Chinese pronunciations, to represent Japanese words of the same or related meaning.

The resulting collection of characters is extremely complex, so learning them usually requires more guidance than handouts and homework can provide.

“Japanese is the most complex language for writing in the world,” said Arno Bosse, the project’s technical manager. “That’s why ‘Kanji alive’ is really a necessity. Without it, students would be having a much harder time.”

Before “Kanji alive,” Lory found that her students wanted to spend much of their in-class time learning kanji, but a full and demanding syllabus made that impossible. As a result, many students found it difficult to master all of the assigned kanji, though competence in the kanji is essential.

“Our short time has to be spent working on conversation,” she said. “Now this is possible. With this kind of Web tool we can save time and they can learn the kanji whenever they wish—24 hours a day from wherever they are outside of class.”

Though simple to use, “Kanji alive” was not easy to create. A team of more than a dozen people and the help of staff of the Digital Library Development Center, the Digital Media Lab, Networking Services and Information Technology, and ARTFL (Project for American and French Research on the Treasury of the French Language) helped get it up and running. Beginning in 2002 and using new graphic tablet and video compression technology as it became available, the program developers worked on the program and its Web site. It has evolved into a language tool with about 850 kanji, and will be finished this spring when about 1,200 kanji are available.

Though not yet in its final form, the Web site already is getting a lot of attention. Other universities, including the University of Rhode Island, Stanford University, Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium, the University of Victoria in Canada, Simon Fraser University in Canada and the Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden, have introduced “Kanji alive” as a learning aid.

Lory’s Web site is even getting noticed in Japan. After being approached by a group of Japanese businessmen, she now plans to create a Japanese version of the Web site as a teaching aid for Japanese elementary school children. It will debut in the new year.

“It’s a lot of work, but it’s worth it,” Lory said. “In my classes, there are no questions about kanji anymore, yet students have a deeper understanding of kanji than before.”

“Kanji alive” can be used on Macintosh or personal computers and does not require the installation of additional Japanese fonts. For more information, visit http://kanjialive.lib.uchicago.edu.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)