Diyala Project brings beginnings of urban civilization to the Internet

By William HarmsNews Office

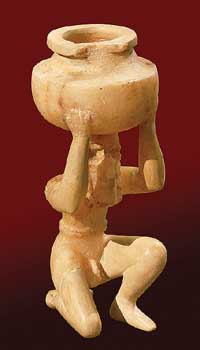

A kneeling, nude male figure holding a vessel is made of alabaster and was found at Shara Temple at Tell Agrab (ca. 2600 B.C.). | |

The story of the origins of urban civilization in Mesopotamia will soon become more accessible to academics and school children around the world as a result of a $100,000 grant to the Oriental Institute’s Diyala Project from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Given as part of the NEH’s “Recovering Iraq’s Past” initiative, the grant will fund the launch of the Oriental Institute’s online Diyala database. The database will contain a full publication of all artifacts recovered during the institute’s excavations on archaeological sites in the Diyala River Basin northeast of Baghdad between 1930 and 1936. These excavations were the most carefully executed and documented in modern-day Iraq of their time. When completed, the Web site will contain the largest single online collection of excavated artifacts from ancient Mesopotamia available in the world.

The Web site will have particular value in the wake of the looting of the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad in April 2003. About half of the objects gathered in the excavation were located in the Iraq museum. Although some 600 Diyala cylinder seals have been confirmed to be missing, all of these objects were photographed during the institute’s excavation. The photographs now form a vital component of the Diyala database.

“The Diyala Web site is a revolutionary database and research tool because it will be able to integrate many different kinds of analysis,” said Gil Stein, Director of the Oriental Institute. “It also provides a way to search the whole range of different kinds of field records of artifacts, architecture, texts and stratigraphy in a completely new way. This is something that has never been possible to do before, and it will provide us with major new insights.

“It is also revolutionary in the way it links two spatially separated collections of artifacts—one essentially inaccessible in Baghdad and one in Chicago. I think this project may well represent the future of archaeological publication,” Stein said.

Clemens Reichel, a Research Associate at the Oriental Institute, is the principal investigator for the project, and George Sundell, a retired data architect, serves as the project’s database designer. Volunteers are helping with data entry and the scanning of photographic negatives and archival material.

The Oriental Institute’s Diyala Expedition remains one of the most important archaeological projects in Iraq’s history. It was the first expedition that established a comprehensive, chronological sequence for the archaeological material from Mesopotamia’s early history.

Working at the sites of Tell Agrab, Tell Asmar, Ishchali and Khafaje, the Oriental Institute team uncovered temples, palaces, domestic quarters and workshops, dating from 3200 to 1800 B.C., a time when large territorial states emerged in Mesopotamia, urban centers were developed and writing was invented.

“The data recovered during these excavations exposed a cross section through most aspects of urban life in ancient Mesopotamia, such as its political organization, religion, social organizations and economic interactions,” Reichel said.

Half of the objects recovered in the digs were taken to the Oriental Institute, and many of them are now on display in the Mesopotamian Gallery. Other objects include stone vessels, tools, weapons, cosmetic sets, metal vessels, inlays, clay tablets and stamp seals, items of artistic value as well as useful everyday value.

As these artifacts were excavated, archaeologists took careful notes of the contexts in which these objects had been found. Their meticulous record-keeping, housed in the Oriental Institute’s Museum Archives, includes field plans, field and object photographs, field object registers, notebooks, and diaries. All of these sources, both published and unpublished, will now be scanned, indexed and integrated into the project’s online database, providing a comprehensive research tool for scholars who wish to further investigate the Diyala site excavations.

Beginning in 1937, several volumes, mostly on the architecture and key finds from these sites, were published as part of the Oriental Institute’s publication series. Its final volume, Miscellaneous Objects from the Diyala Region, which would have included over 12,000 items, was never published.

“Perhaps it is fortunate that this book never materialized—its title would have severely understated the significance of this material, which represents the large majority of finds from the Diyala excavations, consisting of objects that touched upon all aspects of Mesopotamian life,” Reichel said.

With a 1994 NEH grant, McGuire Gibson, Professor in the Oriental Institute, who has since brought attention to the perils posed to Iraqi archaeology in the wake of the war in Iraq, began using computer technology to catalogue the information. As technology changed, the project evolved, and researchers decided to publish the project on the Web rather than in a book.

The database also was configured for use as an elaborate research tool for students working on their dissertations. Reichel’s own dissertation, “Political Changes and Cultural Continuity at the Palace of the Rulers at Eshnunna (Tell Asmar) between 2070-1850 B.C.,” drew heavily on some 2,000 cuneiform texts found during the Diyala expedition. By developing search programs to query the database, he was able to establish genealogical lines for palace officials that extended over almost 200 years.

While primarily intended to serve as a scholarly publication, the Web site also will address the interest of the general public.

“Our site will feature educational components that could easily be used as teaching tools in schools,” Reichel explained. “By ‘walking’ on the computer screen through the plan of a selected building, for example, students will be able to call up images and descriptions of artifacts found in each room.

“Such exercises will not only help students do their own virtual digging, but also will help them understand the importance of properly recorded archaeological context for ancient artifacts—an important message at a time when so many objects from illicit excavations in postwar Iraq are flooding the antiquities market,” Reichel said.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)