Manuscripts of ‘father of blood bank’ on display at Regenstein

By Jennifer CarnigNews Office

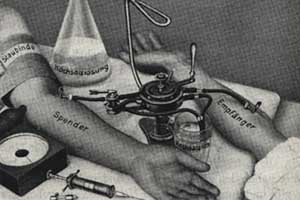

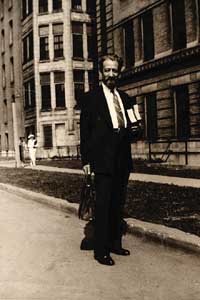

Ex Libris Bernard Fantus M.D., bookplate, no date.  An illustration from James Blundell’s Researches Physiological and Pathological: Instituted Principally with a View to the Improvement of Medical and Surgical Practice, published in 1825 in London. The work is from the John Crerar Collection of Rare Books in the History of Science and Medicine. All of these documents are on display at Special Collections’ exhibition “Dr. Bernard Fantus: Father of the Blood Bank.”  P. Clairmont, et. al. Die Bekämpfung des Blutverlustes durch Transfusion und Gefäßfüllung, Leipzig: Georg Thieme, 1928. Therapie in Einzeldarstellungen, John Crerar Library.  An un-dated photograph of Bernard Fantus in front of Cook County Hospital | |

In March 1937, an event occurred in Chicago that, although little noticed at the time, profoundly altered the history of medicine: Bernard Fantus opened what is now considered the world’s first blood bank in Cook County Hospital. In an exciting development for the University, Fantus’ niece, Muriel Fantus Fulton, has donated her late uncle’s papers to the University Library.

Those interested in the history of medicine can now learn about Fantus’ legacy firsthand with the opening of “Dr. Bernard Fantus: Father of the Blood Bank,” a new exhibition in the Special Collections Research Center at the Joseph Regenstein Library.

A compilation of journal entries, drawings and letters—including one to Fantus’ family from the late President Ronald Reagan—the exhibition sheds light on the process of blood storage and transfusion that now saves nearly five million American lives each year.

Before Fantus opened the first blood bank, blood transfusions often involved either directly connecting the veins and arteries of the donor and the recipient, or trying to pump un-typed blood into the donor before the inevitable clotting set in. Needless to say, it often failed. The procedure also was restricted to patients in the gravest condition and basically used only as a last resort.

By the time of Fantus’ death in 1940, blood banks were springing up all over the country, forever changing the world of medicine. The entire practice of modern surgery would be impossible without the quick, easy and safe access to blood that Fantus introduced.

The blood bank, a term Fantus coined, was a crowning achievement for a doctor with an already rich career. Fantus was one of the country’s foremost experts on pharmaceutics and perfected the practice of candy-coating medicine for children. He also did work on hay fever, and in a less successful but noble attempt to stop Chicagoans’ sneezing, he had city workers attempt to remove the ragweed in the area.

“Researching Chicago Medical History: Sources in the University of Chicago Library” accompanies the exhibition honoring Fantus’ contributions. This companion exhibition highlights some of the most important archival source materials on Chicago medicine in the Special Collections Research Center, including selections from the medical manuscript collections of the John Crerar Library.

Tracing themes in Chicago medicine from the early pioneering doctors of the 1840s to recent programs of medical research, the exhibition displays physicians’ letters, journals, lecture notes, photographs and an antiquated set of amputation instruments.

Both the Chicago medical history exhibition and the showcase on Fantus will be on display until Monday, Feb. 7, 2005, on the first floor of the Joseph Regenstein Library. For more information, call (773) 702-8705.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)