Fossil suggests long neck made this reptile an effective predator

By Greg BorzoField Museum

| |

The well-preserved fossil of a newly discovered reptile species may explain the function of an extremely long neck—a feature for which some protorosaurs are known and which has puzzled scientists for decades.

The Protorosauria is an order of diverse predatory reptiles that lived as far back as 280 million years ago. Scientists have never been able to figure out the function of the extremely long neck that characterizes some species of this group, including Tanystropheus longobardicus, which was discovered in the 1850s.

About twice as long as its trunk, Tanystropheus’ neck has 12 vertebrae along which extend elongated cervical ribs. Years ago, scientists concluded that the long, stiff neck was more or less a consequence of growth patterns rather than a specific functional adaptation.

The new species of protorosaur, however, provides additional clues and suggests that the long neck in these animals may have been part of a unique and very effective method for capturing prey in water.

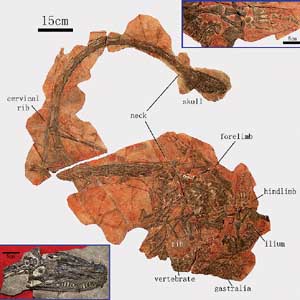

Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, which means “terrible-headed lizard from the Orient,” was recently discovered in southern China. It has a neck made up of 25 vertebrae, also with elongated cervical ribs extending along them. In an article published in Science Friday, Sept. 24, the authors describe how the neck may have been used to capture prey.

“This is important research because we have finally explained the functional purpose of this strange, long neck,” said Olivier Rieppel, a co-author of the Science paper and chair of geology and curator of fossil amphibians and reptiles at Chicago’s Field Museum. “It allowed an almost perfect strike at prey, which usually consisted of elusive fish and squid.”

Prey in water is slippery, and any movement toward it not only alerts the prey of an attack but also creates a pressure wave that could push the prey away. Fish and some turtles combat these factors with suction feeding, i.e., pulling the prey into their months by rapidly expanding the mouth cavity.

Crocodiles and alligators use a different approach when feeding in water. They catch prey with their flat head and pincer jaws, which allow them to strike laterally, cutting through the water while minimizing the force that pushes the prey away.

Dinocephalosaurus apparently took yet another approach. When it thrust its head forward to capture prey, the ribs along its neck would splay outward. This would increase the diameter of the esophagus, creating a suction force that would swallow the pressure wave created by the lunging head, along with the prey.

“The unusual neck morphology of Dinocephalosaurus would have allowed it to suction feed, a feeding mode previously unknown for fossil aquatic reptiles,” said Michael LaBarbera, Professor in Organismal Biology & Anatomy. “But suction feeding in Dinocephalosaurus was different from suction feeding in any other animal. Rather than expand the volume of its mouth to suck in prey, Dinocephalosaurus expanded the volume of its throat, in many ways a more effective approach.”

In addition, the long neck allowed Dinocephalosaurus to draw near its prey stealthily so it would have less of a chance of being detected. “To a fish in murky water, Dinocephalosaurus’ head would have initially looked like another animal its own size, but by the time the fish was able to see Dinocephalosaurus’ body, it would already have been lunch,” LaBarbera said.

“Dinocephalosaurus sheds new light on the evolution of protorosaurs and the functional morphology of these long-necked marine reptiles,” said Chun Li, lead author and assistant research fellow at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing.

“When Tanystropheus, the first long-necked protorosaur to be found, was discovered in Europe in the 1850s, it raised so many questions that it was called a ‘biomechanical nightmare,’ ” Chun added. “And it generated fiery discussion among scientists as recently as the 1980s.”

Dinocephalosaurus is 230 million years old and dates from the Triassic. It has 25 cervical vertebrae to Tanystropheus’ 12, which might have made its neck a little more flexible.

“These two species are not very closely related, which demonstrates that this strange, long neck evolved twice within the group of protorosaurs,” Rieppel said.

Dinocephalosaurus’ neck measures 1.7 meters, while its trunk is less than 1 meter long. Some of its cervical ribs, which are connected to neck vertebrae, span several intervertebral joints. The ribs increase in length from the front of the neck to the back of the neck, bridging more joints near the base of the neck than near the head.

Unlike most protorosaurs, Dinocephalosaurus was fully aquatic, although it might have laid its eggs on land.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)