University instrument collects data on Stardust

By Steve KoppesNews Office

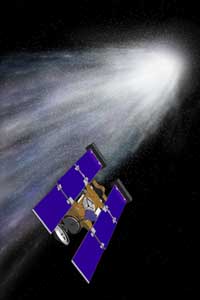

An artist’s rendering of the Stardust spacecraft shows it flying at a distance of approximately 150 miles from the Comet Wild 2. University scientists published results of their collected data in the June issue of Science. | |

Two swarms of microscopic cometary dust blasted NASA’s Stardust spacecraft in short, intense bursts as it approached within 150 miles of Comet Wild 2 last January, according to an instrument aboard the spacecraft that was designed at the University.

“These things were like thunderbolts,” said Anthony Tuzzolino, a Senior Scientist at the University’s Enrico Fermi Institute. “I didn’t anticipate running into this kind of show.” Tuzzolino and Thanasis Economou, also a Senior Scientist at the Enrico Fermi Institute, reported their findings in the Thursday, June 17 issue of the journal Science.

The materials streaming from a comet range in size from particles that could fit on the head of a pin to boulders the size of a truck. Stardust mission planners correctly estimated that their spacecraft could safely avoid the hazardous larger objects by passing the comet at a distance of approximately 150 miles and by using very effective dust particle shields.

Based on the data collected by the Dust Flux Monitor Instrument, Tuzzolino and Economou estimate that NASA achieved its goal of collecting at least 1,000 samples measuring at least one-third the width of a human hair or larger during the flyby.

The Stardust spacecraft is scheduled to return the samples to Earth in January 2006. Scientists will study the samples, the first ever returned to Earth from a comet, for insights into the early history of the solar system.

The Dust Flux Monitor Instrument collected data for 30 minutes when the spacecraft passed closest to the comet in early January. Stardust encountered the first swarm of dust particles when the spacecraft passed within 146.5 miles of the comet’s nucleus. The monitor detected a second intense swarm after passing the comet when the spacecraft was approximately 2,350 miles from the nucleus.

“We believe that we see fragmentation of large dust lumps into swarms of small particles after they come out from the nucleus,” Economou said.

In between the particle swarms, the impact of which lasted just a few seconds each, the dust monitor went for periods of several minutes before it detected another particle.

This is not Tuzzolino’s first encounter with a comet, though it is by far the closest. He helped design, build and test the Dust Counter and Mass Analyzer instrument that passed Comet Halley at a distance of 5,000 miles or more in 1986, while aboard two Soviet Vega spacecrafts. Halley had emitted a spray of dust “much smoother” than that of Wild 2, Tuzzolino recalled.

“In general, one thinks of a comet as emitting gas and dust in a nice, uniform steady state, sort of like a hose,” he said. Halley did show fluctuations, “but not to this extent.”

The dust monitor detected its first impact when Stardust was 1,010 miles from the cometary nucleus. The last impact was recorded at a distance of 3,500 miles as the spacecraft sped away. During one intense event, the dust monitor detected more than 1,100 impacts in one second. The largest particle measured during the cometary flyby measured an estimated five-hundredths of an inch in diameter.

An instrument similar to Chicago’s Dust Flux Monitor Instrument is a component on NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn. Cassini’s High-Rate Detector, which Tuzzolino also built, is part of a larger instrument, Germany’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer, which studied the ice and dust particles that form the major components of Saturn’s ring system.

On Wednesday, June 30, Cassini became the first spacecraft ever to orbit Saturn.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)