Archaeologists review loss of valuable artifacts one year after looting

By William HarmsNews Office

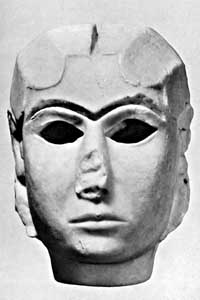

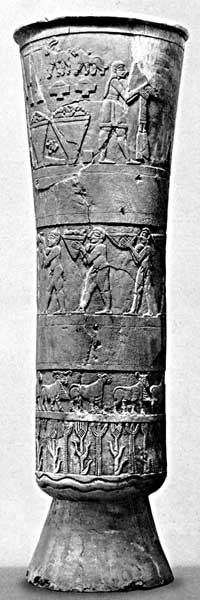

This artifact, the Lady’s Head from Warka (ancient Uruk), is made of marble and dates to 3000 B.C. It was stolen from the Iraqi National Museum in April 2003 and recovered in September.  This modern impression of a cylinder seal from Tell Billa, which shows two cultic scenes involving a boat ride and a procession toward a temple, is missing from the Iraqi National Museum collection. The item dates to 3000 B.C.  The Akkadian Seal and modern impression, showing a Mesopotamian sun god with a human torso in a boat, is from Tell Asmar (Iraq). The seal, which dates to 2200 B.C. and is part of the Oriental Institute collection, is similar to others lost in the looting in Iraq.  The Bassetki Statue is the lower part of a copper statue in the shape of a squatting hero. It dates to 2200 B.C. It was stolen from the museum in April 2003 and recovered in October.  This large cylindrical vessel made of alabaster displays cultic and daily life scenes. It was discovered in Warka (ancient Uruk) and dates to 3000 B.C. Stolen in April 2003 from the Iraqi National Museum, the vessel was recovered, in pieces, in June.  This image shows the vase in its prewar condition, and the image immediately above it shows the vase's condition at the time of its return in June. |

A year after the looting of the Iraqi National Museum, Oriental Institute archaeologists continue to track missing artifacts. And their work is playing a pivotal role in helping recover items stolen from the museum in Baghdad between April 9 and 11, 2003.

“This event provoked great outrage around the world and attracted new attention by both media and the public on the Mesopotamian civilization, Iraq’s cultural heritage,” said Oriental Institute Research Associate Clemens Reichel. Reichel initiated a Web-accessible database to document the destruction and theft of artifacts last April, following the museum’s looting.

Other Oriental Institute scholars continue their work to help protect Iraq’s sites and antiquities, here and overseas. McGuire Gibson, Professor in the Oriental Institute, attended numerous emergency meetings and conferences held by national and international organizations, including the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. In May 2003, Gibson went to Iraq as part of a National Geographic team to investigate firsthand the situation at the museum and at Iraq’s archaeological sites.

Reichel and Charles Jones, Head Librarian for the Oriental Institute’s Research Archives, are continuing their work on a Web database, which documents the losses of the Iraq museum as well as of Iraq libraries. The database is accessible at http://oi.uchicago.edu, the institute’s Web site.

Press reports following the museum looting last April initially had suggested a total loss of the museum’s collection—about 170,000 registered objects.

“Such reports fortunately turned out to be exaggerations; thanks to the foresight of the museum staff, a lot of objects had been stored away in safe locations before the outbreak of hostilities,” Reichel explained.

Among the items protected from destruction were the so-called Nimrud Gold Treasure (860 to 700 B.C.), gold finds from the Royal Tombs of Ur, dating from about 2600 to 2400 B.C., and a life-size head of an Akkadian king, cast in copper and found at Nineveh, which dates to ca. 2200 B.C.

As the year developed after the looting, reports both highlighted the damage and confused the issue. Some news outlets began to speak of “only 40” objects being taken from the museum.

Those reports, said Reichel, “only referred to objects on display in the gallery but omitted any reference to objects stolen from the storerooms and magazines of the museum. The losses encountered there were sizeable, though even now it remains difficult to put an exact figure on it.”

The destruction of the archives that recorded information about the museum holdings complicated the job of totaling the loss. “By fall 2003, the figures quoted by Donny George, director of the Iraq Museum, and Col. Matthew Bogdanos, (U.S. Marine Corps) who led a U.S. team investigating the museum looting last year, put the number of objects stolen at over 10,000. This figure, however, has recently been revised by George to about 15,000 pieces, indicating this tally is far from final at this point,” Reichel said.

In a visit to the Oriental Institute, George recognized the contributions of its scholars to the preservation of the museum’s materials.

Many artifacts were recovered throughout the last 11 months. By early February, as many as 5,000 objects were reported to have been recovered in Iraq or abroad, including 1,000 pieces in the United States, 700 in Jordan, 500 in France and 250 in Switzerland.

Pieces recovered in police raids in Iraq included two of the most famous pieces from the Iraqi National Museum’s collection—the Lady’s Head from Warka, a beautifully sculpted marble head of a woman, dating to about 3000 B.C., which was recovered in September, and the Bassetki Statue, the lower half of a sitting figure of a hero, cast in copper and dating to ca. 2200 B.C., which was recovered in October.

Other pieces were returned anonymously and voluntarily, including the famous Warka Vase, an alabaster vase decorated with elaborate relief scenes that dates to about 3000 B.C. This vase was returned in June, broken into numerous pieces, though likely restorable.

“Mixed in with the joy over the recovery of these pieces is the sorrow over the loss of other objects, which will remain difficult if not impossible to recover. This list may well be topped by 4,795 cylinder seals, which originally had been thought to be safe in the museum’s storerooms and whose loss was only noted in June,” Reichel said.

These objects, often made of precious stones, decorated with elaborate images and sometimes bearing inscriptions, were ancient bureaucratic devices, used to verify business or legal transactions by impressing the seal into documents inscribed on clay tablets. In modern times, however, these seals have become highly desirable collectors’ items, which often sell for astronomical prices at auction. Many of the seals from the Iraq Museum could end up in the hands of collectors worldwide, never to be seen again.

In terms of archaeological losses, the looting of the museum may well be dwarfed by the continual destruction of archaeological sites all over Iraq by looters. This looting has touched upon well-known sites such as Nippur, home of an archaeological expedition of the Oriental Institute, Umma, Lagash, and Isin, but many more unexcavated sites are destroyed by the unsystematic onslaught of pick axes used by the looters throughout the country.

The loss in archaeological data is impossible to quantify but clearly has reached disastrous dimensions. Although coalition forces have taken measures to protect some of the key sites in Iraq, archaeologists contend those measures have been inadequate.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)