Oldest-known arm bone found explains animal evolution from water to land

Catherine GianaroMedical Center Public Affairs

|

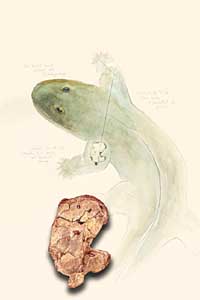

How land-living animals evolved from fish has long been a scientific puzzle. An important part of the mystery is the transformation of the fins of fish into the arms and legs of humans’ ancestors. University paleontologists Michael Coates and Neil Shubin and Ted Daeschler from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia found a 365-million-year-old fossil that sheds light on this transformation.

In the Friday, April 2 issue of Science, the researchers describe this bone, a humerus from the Late Devonian Period found in Pennsylvania. It is the earliest of its kind from any limbed animal, and the specimen bridges the gap between the fins of fish and the limbs of amphibians.

The newly discovered arm bone is a keystone to new comparisons of fish and limbed animals because it represents a part of the anatomy where many functional changes took place. “It’s a mosaic of primitive fish and derived amphibian,” said Shubin, lead author of the paper and Professor and Chairman of Organismal Biology & Anatomy. This integral piece of the evolutionary puzzle not only shares features with primitive fish fins, but also has characteristics of a true limb bone.

“This bone is a lot more robust than a humerus from any of the ancient species,” said Coates, an Associate Professor in Organismal Biology & Anatomy who specializes in fish-tetrapod transition and the divergence of modern lineages. “Relative to other tetrapods, this is almost over-engineered. There’s a massive space for the attachment of substantial muscle going across to the chest.” Action of these muscles would have produced a motion similar to a pushup, which is why the researchers believe that the arm bone served to prop up the body. They argue that “this function represents the intermediate condition between primitive steering and braking functions in fins and the derived aquatic or terrestrial walking gait.”

Shubin said, “The size and extent of these muscles means that the humerus played a significant role in the support and movement of the animal.” Less elaborate versions of these muscles also are seen in some fish.

“When this humerus is compared to those of closely related fish, it becomes clear that the ability to prop the body is more ancient than we previously thought,” Coates said. “This means that many of the features that we thought evolved to enable life on land originally evolved in fish living in aquatic ecosystems.”

Daeschler and Shubin collected the specimen in 1993 from a “seemingly unlikely place,” Daeschler said—a highway roadside in north central Pennsylvania. The layered rocks along the Clinton County Road were deposited by ancient stream systems that flowed during the Late Devonian Period, about 365 million years ago. Enclosed in these rocks is fossil evidence of an ecosystem teeming with plant and animal life.

“We found a number of interesting fossils at the site,” Daeschler said, “but the significance of this specimen went unnoticed for several years because only a small portion of the bone was exposed and most of it lay encased in a brick-sized piece of red sandstone.”

In 2001, when academy fossil preparator Fred Mullison excavated the bone from the rock, the importance of the new specimen was immediately evident.

“We knew it was a humerus,” Coates said, “but it was an entirely different kind. We had never seen one like it before.”

The National Geographic Society and the National Science Foundation funded the research. Coates, Daeschler and Shubin plan to return to the site in May.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)