SSA Professor discovers smokers are more aware of secondhand smoke’s harmful effects

By William HarmsNews Office

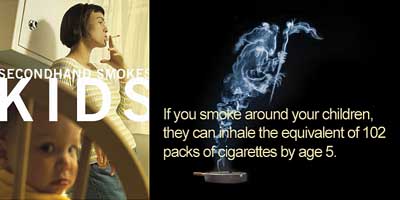

Advertisements like the one above, created by the state of Washington Department of Health, may have contributed to a decline in secondhand smoke in households, as did the restrictions on smoking in public places. Research shows that although smoking dropped modestly between 1992 and 2000, awareness of secondhand smoke’s harmful effects has increased. |

Despite a modest drop in smoking between 1992 and 2000, exposure to secondhand smoke in American homes fell significantly, according to a study co-authored by Harold Pollack, Associate Professor in the School of Social Service Administration.

“We were encouraged to find decreases in home exposure across all large racial, ethnic, educational and income groups,” Pollack said. “The small observed declines in smoking prevalence, both in the general population and in adults with minor children, do not account for the magnitude of the decline in home environmental tobacco smoke.”

The decline in permitting smoking in the home may be due to increased concern about secondhand smoke brought on by restrictions in the workplace and in public areas, such as restaurants, researchers suggest.

During the eight-year period, smoking fell from 26.5 percent of the population to 23.3 percent. Some demographic groups, however, had particularly high rates of smoking among parents with children at home. Those groups nonetheless showed significant declines in environmental tobacco smoke, or ETS.

In households where the mother had not completed high school, for example, ETS exposure declined from 49 percent in 1992 to 35 percent in 2000. Among households in which the mother had completed graduate education, ETS exposure declined from 11.2 percent to 6.7 percent.

Among Hispanics, ETS exposure dropped from 24.4 percent to 16.1 percent. In African-American households, ETS exposure dropped from 37.2 percent to 30.3 percent.

Overall, the ETS exposure in homes with children declined from 36 percent to 25 percent between 1992 and 2000.

The data came from the National Health Interview Survey. Pollack was joined in his work with former colleagues at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, Soheil Soliman and Kenneth Warner. Their findings were published in the paper “Decrease in the Prevalence of Environmental Tobacco Smoke Exposure in the Home during the 1990s in Families with Children” in a recent issue of the American Journal of Public Health.

“Ken and I are especially delighted to see strong doctoral students such as Soheil join the research game as lead authors,” said Pollack.

The researchers found that there was general awareness during both comparison years about the danger of secondhand smoke. For children those dangers include asthma, respiratory infections, sudden infant death syndrome, the common cold, pneumonia, bronchitis and other illnesses. The consequences are especially severe for children under age 5.

The survey did not identify reasons for the drop in smoking at home, though another study in California showed a relation between restrictions on smoking in public and the increase of households that consider themselves smoke free, Pollack said.

“Initiatives such as the passage of clean indoor air laws may have signified a change in society’s acceptance of ETS exposure; this shift in social norms also may have translated into changes in behavior,” he said.

The California Tobacco Survey showed that the proportion of households considering themselves smoke free doubled between 1992 and 1999.

“Smokers reporting a no-smoking policy in the home nearly tripled, from 15.8 percent in 1992 to 48.6 percent in 1999, whereas the change in homes of nonsmokers went from 37.6 percent to 73.7 percent,” Pollack said.

“The decline in home ETS exposure may indicate that the campaign to reduce ETS in work sites and public places also influences home ETS exposure. This should translate into improvements in the health of families, especially the health of children,” he said.

Pollack joined the SSA faculty earlier this year. He has published widely in public health and public policy research, and has served on two committees of the National Academy of Science’s Institute of Medicine.

Formerly a Robert Wood Johnson scholar in health policy research at Yale University, Pollack also has taught health management and policy at the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

He received a B.S. in electrical engineering and computer science from Princeton University and his M.A. and Ph.D. in public policy from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)