Dietler discovers statue in France that reflects an Etruscan influence

By William HarmsNews Office

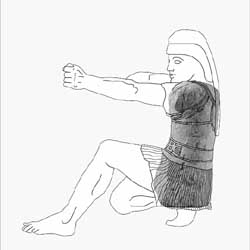

This image depicts the reconstruction of the statue Michael Dietler found at Lattes in southern France. An image of the statue is positioned in the torso area of the figure of the warrior. |

A life-sized statue of a warrior discovered in southern France reflects a stronger cultural influence for the Etruscan civilization throughout the western Mediterranean region than previously appreciated.

Michael Dietler, Associate Professor in Anthropology, and his French colleague Michel Py have published a paper in the British journal Antiquity on the Iron Age statue, found at Lattes, a Celtic seaport Dietler is studying in southern France.

They found the fine-grained limestone statue in the door of a large courtyard-style house they are excavating in the ancient settlement, which is five miles south of the modern day city of Montpellier. The statue dates from the sixth or early fifth century B.C.

“The house is different from any we have seen in the area,” Dietler said. It is much larger than other houses in the settlement and does not follow the traditional indigenous architectural styles, nor is it precisely like those of the Etruscans or Greeks.

The team discovered the statue embedded in a door, indicating it had been reused as part of the structure when the house was built sometime around 250 B.C. It is the only statue found so far at the site.

“One thing that is unusual about the statue is that it was found in a secure archeological context. Most of the other statues we have from this period were discovered in the 19th century, for example, and we don’t know for sure where they came from,” Dietler explained.

The statue, which was damaged while serving as a doorjamb, is unusual in other ways. From what remains of it, largely a torso, scholars have determined the statue is of a kneeling warrior holding a weapon, such as a bow or a spear. Most other statues from the era are of warriors seated in cross-legged positions.

Body armor and clothing commonly seen in Italy and Spain decorate the statue. Previously, scholars have thought that the objects represented on statues found in the region demonstrated that northeastern Spain influenced their design. But Dietler’s work suggests there has been some confusion about these cultural influences, and that some likely originated in Eturia, with a complex circulation of metal objects throughout the western Mediterranean.

Dietler’s statue has two round discs that are carved in relief on the chest and back of the warrior. Also carved on the statue are four smooth cords superimposed over a ridged strap that passes over the top of the shoulders and along the middle of the torso, encircling the arms. On the back disc is the effaced tail of a crest of a helmet.

The warrior is dressed in a finely grooved pleated skirt, which is encircled with a wide belt. The belt buckle on the Lattes warrior is one of the strongest clues of the statue’s creation date, as examples of this type from graves in Spain and Italy are no longer found on statues dated after the early fifth century B.C.

Etruscans may have lived at Lattes at one time as part of a trade enclave. They were still apparent in about 475 B.C., when the settlement became part of the Masaliote sphere of trade, based in a larger community of Greek colonists nearby where modern Marseilles is now located.

Lattes is an important site for understanding the Iron Age in the western Mediterranean and the history of ancient Greek and Roman colonialism. It was occupied from the sixth century B.C. to the second century A.D., at which time the lagoon that connected it to the Mediterranean filled with silt, and residents gradually abandoned the community.

The site, which was known as Lattara in ancient times, was rediscovered in the 1970s as a result of urban expansion from Montpellier. After initial archaeological exploration showed there was an important site in the area, it was preserved, and a major museum and archaeological research complex was built on the edge.

French researchers, who are joined by Dietler and colleagues from Spain and Italy, conduct an annual excavation of the site, which also is an international field school for graduate students. They have revealed, in addition to unique shell art, other unusual features of the community.

At the period of its greatest extent, Lattes was one of the largest sites in the region, covering approximately 50 acres. Unlike other communities of the period, it was a fortified lowland site rather than a hill fort, most of which were much less than half Lattes’ size.

The port was an important gateway to the Celtic residents of the interior and connected them with Etruscan and Greek traders. Outside the Greek colony at Marseilles, Lattes has the first evidence of olive oil and wine production in France.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)