University’s SALRC aims to improve linguistic intelligence

By Seth SandersNews Office

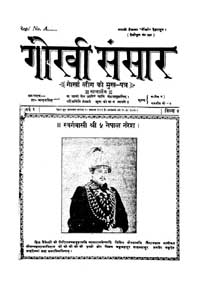

The Digital South Asia Library Web site, a project of the University’s South Asia Language Resource Center, features several microform scans of the weekly Nepali newspaper, Gorkha Sansar. The paper, created by the Nepali intellectual Thakur Chandan Singh, was published from 1926 to 1929. It specifically focused on uplifting the Nepali Gurkha diaspora community while it reported on the residents of Nepal more generally. The paper was banned inside Nepal, but it remained a popular medium of expression for the diaspora community. Above (left) is the front page of Gorkha Sansar published Nov. 20, 1926, and (right) the front page of the issue published Aug. 24, 1928. |

Politicians on both sides of the aisle are beginning to realize that our inability to talk to or understand the rest of the world is not just parochial-it is dangerous for everyone involved.

Perhaps the most forward-looking and well-funded attempt to change this picture-including, but going far beyond the languages of flashpoints like Pakistan and Afghanistan-may be the University’s South Asia Language Resource Center.

House Intelligence Committee chairman Porter Goss is a strong Republican supporter of the CIA, but recently Goss berated American intelligence for its ignorance of foreign languages. Meanwhile, Democratic presidential candidate Wesley Clark insists that America’s military troops should have been taught Arabic-and Washington seems to be getting the message. The CIA has begun a new recruitment campaign with ads reading, “Intelligence speaks many languages.”

But America’s intelligence weakness and the challenge ahead go deeper than that, argued Steven Poulos, head of Chicago’s recently congressionally funded SALRC initiative. He said a reactive, ad hoc approach to language learning would never build real competence. After all, who cared about Afghan languages like Pashto three years ago? And who knows what cultures we may need to understand five years down the road?

The University already has made the first online Pashto dictionary available as part of its Digital Dictionaries of South Asia Project (http://dsal.uchicago.edu/dictionaries/). Now the SALRC is funding development of the first standard Pashto proficiency test and online courses in elementary Sindhi and intermediate Urdu (Pashto, a major language of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and Sindhi and Urdu represent three of the five regional and national languages of Pakistan). And Poulos has something to say about how these languages can be mastered.

“Congress and people like us have to recognize this doesn’t happen overnight. You need a long-term commitment; it can’t be a few years on, a few years off. Right after Sputnik there was a great interest in South Asia, then it died out in the ’70s and ’80s. Some parts of the developing world did remain of interest because of politics and money-war, oil, etc., but it wasn’t consistent. Our project is a model of how you can turn this around. You can develop the people and resources if you take the time. Our technology and teacher training programs will lead to a better classroom presence and classroom environment for these languages.”

The center already has funded eight very different projects. “We brought all of the grantees to Chicago in October, and we did a big tech workshop, showing them the latest in digital video and audio, what copyright issues to watch for in digitizing things, and the latest work in handling our many different scripts.” And new projects are in the works, as a second round of federally funded grant competition closed at the end of November.

The projects range from massive to limited, but all advance knowledge of the rest of the world’s languages, said Poulos. “The University of Virginia has a project to do Tibetan at all levels online,” said Poulos. “They’ve already got loads of video and course materials up on the Web with a multinational group. They came to us because they had a lot of important audio that they haven’t been able to digitize, so we’re funding the transfer and editing of audio they’ve collected from various locations to help people learn Tibetan.”

Two years ago, intelligence services were urgently requesting speakers of Pashto, a language for which no basic proficiency test exists. The SALRC is funding a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania to develop such a test in the Pashto language that can be produced on a CD and conveniently shipped to an examiner.

“Philip Engblom, a lecturer of Marathi in the University’s South Asian Languages & Civilizations, is a parade example of a classically trained teacher adapting to new technologies. He produced the only first-year textbook of Marathi when he barely used computers. Now with our support, he’s completely revisiting his original project to create an online, interactive, first-year Marathi course based on his earlier Marathi textbook.”

Poulos said another direction the center is taking involves pedagogical workshops to raise the level of teaching for South Asian language teachers to that of teachers of many other languages. “We’re disseminating new ideas on how to present culture and use digital material. Many experienced language faculty don’t see a need to change, and recent events have brought many newer instructors into the field with zero experience in teaching. So we’re doing workshops in Berkeley, Madison and other places, trying to raise the level of the classroom,” said Poulos.

“In this regard, a real success,” added Poulos, “is the joint summer session we had at Madison. There were far more students than expected, and they did very well. Similarly, the American Institute of Indian Studies, which sends students to study in India, had more students than in the past. The great advantage of this kind of program for non-South Asia centers-schools like Illinois or UC Santa Barbara or small colleges-is that even if your school doesn’t offer Urdu, you can still take an intensive course here over the summer. It provides an opportunity where there was none before, and this summer we offered nine languages at two different levels.”

But more cutting-edge initiatives such as those of the SALRC are needed nationwide, said Poulos. “The country has to be concerned about South Asia, otherwise people won’t take the languages. Right now it’s just a thing of the moment,” he said. If that continues over the long term, said Poulos, the students, funding or positions will not be there. “These days there are virtually no tenure-track positions being offered in language teaching, only in literature or cultural studies and other trendy areas.”

Directors of the nation’s 14 language resource centers met with officials of the federal government in September. “At the top of our list was what to do to show that this is in all universities’ interests. When I was trained, there were still professors whose main job was to teach languages, but it’s not true anymore-as they retire, they’re replaced by disposable lecturers, so there’s been no future in the field.”

Meanwhile, the SALRC represents one of the field’s, and perhaps the country’s, brighter hopes for changing that future.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)