Phenomenon found in droplets may lead to microscopic uses

By Steve KoppesNews Office

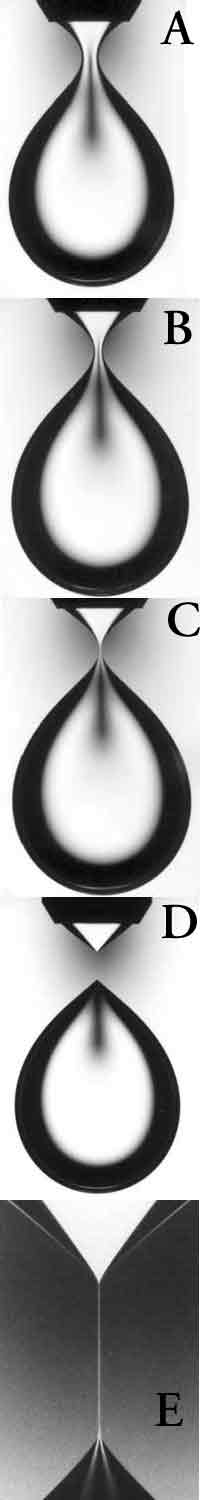

A water drop drips through silicone oil showing that the neck of the drop is initially a smooth parabola around the drop’s narrowest point (images A to C) and then becomes a long and thin thread (images D and E). |

Scientists have long believed that the breakup of all fluids-whether produced by a dripping faucet, a splashing fountain or the sun’s boiling surface-exhibit the same type of behavior. Now a group of scientists has discovered an exceptional dynamic associated with the breakup of a water drop in highly viscous oil. This dynamic could potentially be used to create microscopically small fibers, wires and particles.

The discovery was announced in the Friday, Nov. 14 issue of Science by researchers at Chicago, Purdue University, Harvard University, the New Jersey Institute of Technology and the University of Oxford.

The path to discovery began when Itai Cohen, currently a postdoctoral scientist at Harvard, was a graduate student at Chicago in 1999. For one of his experiments, he dripped water into viscous oil and saw a smooth parabolic shape near the narrowest point, which then transformed into a long and thin thread just shortly before breakup. This is unlike any of the previously observed breakup dynamics.

Cohen and Sidney Nagel, the Stein-Freiler Distinguished Service Professor in Physics and the College, enlisted the aid of Purdue’s Osman Basaran, who ran a series of computer simulations on the water-in-oil breakup process. The simulations conducted by one of his students, Pankaj Doshi, produced results that matched the experimental data and revealed in addition fine-scale details such as velocity and pressure data the experiment could not provide.

A new story emerged when theorists Wendy Zhang, Assistant Professor in Physics and the College, Peter Howell at the Mathematical Institute in Oxford, and Michael Siegel of the New Jersey Institute of Technology were able to show that the smooth profile observed is associated with drop breakup dynamics that are driven by a uniform inward collapse of the viscous oil outside the drop.

Zhang first noticed the possibility of this breakup mode in graduate school but dismissed it because it occurs only if the inside of the drop is essentially stationary, “something that no sensible person would think happens because here’s a drop, it’s breaking. Of course the things inside have to be moving out of the way!” Zhang said.

This apparently impossible dynamic is achieved by the breakup of a water drop in oil because the motion of the water in the drop’s interior is much faster than the motion of the viscous oil on the outside, so that the interior always settles down much faster than the exterior flow. This makes the interior appear static.

As breakup approaches, the two flows become more comparable. This results in the sudden transformation of the smooth parabolic neck into a long and thin thread, estimated to be two millimeters long (eight hundredths of an inch) and eight microns wide (about a tenth the width of a human hair).

“This breakup dynamic is exceptional in that it preserves a memory of the drop shape before breakup down to very small length-scale, right down to the point when the thin thread forms,” Zhang said.

Before its discovery, scientists believed that when a liquid drop breaks, the process of breakup always erases all memory of conditions at the onset of breakup. The persistence of memory during breakup and the subsequent formation of the thin thread potentially opens the way to a new method for producing microscopic structures for electronics, pharmaceuticals and other applications by manipulating fluids on a millimeter scale.

The scientists are quick to point out that despite this new understanding, some aspects of the breakup process remain mysterious. “This drop is breaking up in a way that’s very inconvenient by developing such a long and thin thread right before breakup,” noted Zhang. “It certainly wouldn’t be the way I would do it if I were to prescribe how a drop breaks.”

Nagel noted that the project could only have achieved success by bringing together a team of experimentalists, theorists and simulators.

“Everybody had a little piece of the action,” Nagel said. “It never would have gotten anywhere without experimentation, but it wouldn’t have been understood without theory, and we wouldn’t have known how to connect the two in any way whatsoever if it hadn’t been for the simulation.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)