Abydos: A place with many ancient stories to tell

By William HarmsNews Office

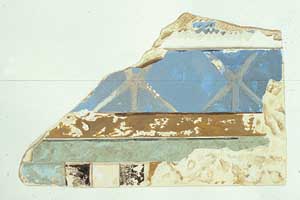

Stephen Harvey pauses for a photo during one of his trips to Abydos.  A watercolor rendition of a fragment of limestone, which shows a band of sky with stars, was found at the top of a wall from the Ahmose pyramid temple.  A painted limestone fragment of a relief from the Ahmose pyramid temple may be part of a battle scene, showing the royal ship of King Ahmose with a royal vulture perched atop the stern of the ship. The fragment may derive from depictions of the historical battles against the Hykos invaders. |

Under the leadership of Egyptologist Stephen Harvey, a team of archaeologists from the University’s Oriental Institute will soon begin to excavate recently discovered buildings from a critical era in ancient Egyptian history.

Earlier this year, the team discovered three new buildings in Abydos, a rich and important archaeological site near Egypt’s last royal pyramid. Also among their findings were walls and related buildings near another pyramid, engraved bricks with the names of people responsible for the construction of the buildings, fragments of decorated limestone temple reliefs, parts of statues, and small inscribed stone slabs used as part of worship that are known as votive stelae.

The discoveries are part of a collection of artifactual documentation that pushes back the date of complex artistic representation of warfare in Egypt. The site has yielded the earliest known paintings of horses and chariots used in battle as well as the earliest known representation of a practice that later became common in battle documentation: paintings of collections of the severed hands of enemies.

But Abydos has other stories to tell, such as those suggesting some women held extraordinary levels of power within their communities. One of the buildings the team discovered earlier this year is a temple that likely was dedicated to Ahmose Nefertary, the wife and sister of the Pharaoh Ahmose, who ruled from about 1550 to 1525 B.C. and built Egypt’s last pyramid. The team also excavated at a pyramid dedicated to another important woman, Queen Tetisheri, grandmother of Ahmose and his wife.

“Abydos spans the entire history of ancient Egypt,” said Harvey, Assistant Professor in the Oriental Institute. “It has pre-dynastic sites with the earliest evidence of hieroglyphic writing, buildings from the first dynasties, and material from the Middle Kingdom period, the New Kingdom period, the Roman era and everything in between.”

Harvey and his team are exploring in the southern part of Abydos, a site between Luxor and Cairo on the west bank of the Nile. At the turn of the century, British archaeologists explored southern Abydos and then abandoned it after discovering a pyramid built for Ahmose, some carved reliefs and a stela from the Amarna period, which came about 200 years after the pyramid construction.

Harvey, who received a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania, began his work at the site in 1993, while a graduate student. He discovered after a few weeks of excavation that the British had not unearthed a vast area of the site, which is anchored by a 35-foot tall mound of sand. The mound marks the site of Egypt’s last royal pyramid, also known as Ahmose’s pyramid.

“The vista from the top of Ahmose’s pyramid is a commanding one, as it looks over the nearby cultivated fields at the ends of the Nile floodplain, as well as the limestone cliffs more than a kilometer away that mark the start of the plateau of the Sahara desert,” he said.

The mound of sand marking Egypt’s last pyramid indicates that pyramid building was being done “on the cheap,” before the practice went out of style. Instead of being built as colossal structures of limestone, the later pyramids often had cores of rubble and were capped with stone or brick.

The stone of Ahmose’s pyramid as well as the brick of his grandmother’s pyramid was taken for other building projects sometime in antiquity. Likewise, the nearby structures were torn down for other building needs. Only foundations and remnants of walls, including reliefs, remain, along with scattered broken limestone and broken artifacts.

But evidence of Ahmose’s value survived the destruction. Among the painted reliefs found early in Harvey’s excavation is a pictorial representation of his conquest of the Hykos, Canaanite rulers who overran the Nile Delta and split apart Egypt around1650 B.C. Ahmose used chariots and horses to push back the foreigners and eventually conquered Palestine to the northeast and Nubia to the south.

These conquests are what make Ahmose such a pivotal figure in Egyptian history. His reign ushered in the New Kingdom, which was a time for imperial expansion and remarkable prosperity under rulers such as Amenhotep III, Tutankhamun and Ramesses the Great. It was the era of building the fabulous tombs in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens on the west bank of the Nile, across the river from the temples of Luxor.

Another pivotal change during the period of Ahmose occurred in burial customs. Before Ahmose, pharaohs were buried in pyramids; after Ahmose, they were buried in tombs carved into mountains. But, what about Ahmose?

Although a mummy identified as that of Ahmose was found in a cache of royal mummies, “No tomb has been found,” said Harvey. “It could be in the pyramid,” he added.

Although his work will be more difficult because of sand that has collapsed on tunnels dug during previous excavations, Harvey intends to excavate the pyramid and look for the tomb of Ahmose.

Other areas around the pyramid have proved easier to deal with, however. In addition to the temple he believes was dedicated to Ahmose Nefertary, the team also found another temple, which will be the focus of more work in January. They also will excavate a large structure that measures 115 by 130 feet, and which may have been an administrative or production center for a cult that developed around Ahmose, who was considered a god.

Located near what is thought to have been a bakery, this administration building may provide clues that underscore one of the site’s fundamental values: it contains structures that are part of a working community. Scholars will learn what role the temple played in the economy and social organization of the community.

In many past digs, much of the area outside a temple was dug and dumped, with artifacts tossed out in the process. But although only fragmentary evidence remains from the southern area of Abydos, it is important information. Each brick, for instance, is stamped with a name, so it is possible to learn who was in charge of a building’s construction phases.

This information can be studied in relation to other texts to gain a better view of life and power in ancient Egypt, Harvey said.

The Oriental Institute’s new Ahmose and Tetisheri Project is being carried out in collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania-Yale-Institute of Fine Arts-New York University Expedition to Abydos.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)