Fishbane’s new book explores the ongoing mythic creativity of the Hebrew Bible and Jewish tradition

By Seth SandersNews Office

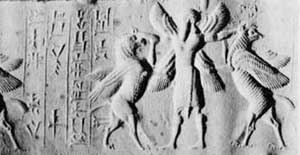

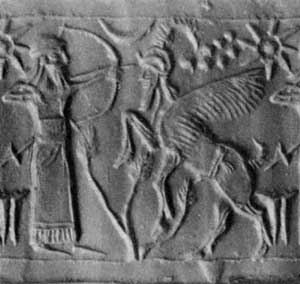

Ancient Babylonian cylinder seals that depict battles between gods and monsters are similar to those found in the Bible, Jewish Midrash and Kabbalah. |

It is a fact that books like Job, Isaiah and the Psalms describe God as a warrior, slaying a primordial dragon in pitched battle. And as Michael Fishbane argues in a new book, far from fading away, “this monotheistic mythmaking emerges more powerfully in classic rabbinic literature, and in a yet more astonishing form, in Kabbalah.”

For centuries, Fishbane said, interpreters have explained away this imagery as mere metaphor or allegory. Even when excavations uncovered similar myths from the Israelites’ ancient Near Eastern neighbors, scholars simply shifted ground, describing the images as “demythologized” myths.

In his newly published Biblical Myth and Rabbinic Mythmaking (Oxford University Press), Fishbane lays down the gauntlet, assembling evidence to show that God’s dragon slaying cannot be explained as a pale, sanitized version of a myth. He offers a new explanation of why and how these images have mattered so much to Jewish tradition.

In this groundbreaking new study, Fishbane, the Nathan Cummings Professor of Jewish Studies in the Divinity School and the College, and Chair of the Committee on Jewish Studies, argues that such attempts to wish away biblical myth are not merely inaccurate, but they have the effect of blinding readers to the real religious vitality of the Bible and Jewish tradition-a vitality he systematically explores and expounds.

Fishbane builds on previous work published in Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel, the first comprehensive study of how ancient Israelites understood and applied their own scriptures, and The Exegetical Imagination, a collection of essays on Jewish interpretations and ritual uses of myth.

In choosing the seemingly paradoxical category of “monotheistic myth,” Fishbane is addressing a strange and distinctive feature of the Bible and Jewish tradition. The great literary critic Harold Bloom once commented about the Hebrew Bible that its “stories remain so original that we cannot read them” because “we are still part of a tradition that has never been able to assimilate their originality.” One could describe Fishbane’s task as an attempt to understand that originality in its full historical sweep.

Fishbane joins a recent wave of scholars of Judaism who are rethinking the meaning of biblical myth as well as scholars of comparative religion, such as Chicago’s Bruce Lincoln, the Caroline E. Haskell Professor in the Divinity School, who are reevaluating myth’s cultural force. Fishbane writes that his goal is “to retrieve, study and even reconstruct the phenomenon of monotheistic myth over the course of two millennia,” from the Hebrew Bible to the great works of Kabbalah.

Fishbane argues that from the start, one is at a disadvantage in understanding myth, since we inherit traditions, ranging from the Greek Sophists to medieval Jewish philosophers to the European Enlightenment, which rationalize it away. He discussed one of his working principles: “If something would be considered myth in an ancient Babylonian or Canaanite source, there is no reason to assume the same material would not have the same force in an Israelite or Jewish setting. These are variants of mythic elements that have gone through a monotheistic filter. This does not mean that imagery has been softened, just that it occurs in an ancient Israelite context. These images would not have been mere ‘metaphors’ for the Babylonians, and neither would they have been mere metaphors for the Israelites.”

Yet Fishbane does not see a myth behind every image: “At the same time I go through a range of genres, indicating where the material veers off into more figurative uses. Ancient Israel was not cut from one cloth: rather, there is a spectrum ranging from material with great mythic resonance to material that is mainly a literary topos.

“The same principles affect my study of interpretation and storytelling in early Jewish Midrash. People assume monotheism implies the impossibility of myth. But what’s interesting is that certain Rabbinic myths, like God’s dragon-slaying or his abandonment of and lamentation for the temple, actually show a greater vibrancy than similar topics found in the Bible, matching that of the ancient Near East. There was an old and ongoing mythic tradition in Israel, much of which did not surface in the Bible. But much of it does surface in Midrash and later in Jewish religious culture.”

But the Rabbis’ creativity does not stop there. Fishbane explained, “The other innovation within rabbinic material is the way interpretation both expands old myths and creates new ones.”

Certain images now appear that the Israelites might never have imagined. “Among the themes that only emerge in rabbinic interpretation are that of God actually enduring suffering and going into exile along with the Jewish people. The third section of the book focuses on this increasing boldness and creativity. One of the striking things about the first great Kabbalistic work, the Zohar, is the very ancient myth of God’s building the world on the slain dragon’s body. Here, a theme already known in Babylonian literature, but only hinted at in the Bible, is elaborated in the much larger and more complex world of Kabbalah.” In these instances, Jewish tradition has actually expanded its mythmaking power so that in the Zohar there is “virtually no word or image in the Hebrew Bible that is not a potential myth.”

Why have people been so reluctant to examine this rich legacy? Fishbane argues that this reluctance is defensive. In his analysis of earlier scholars who pose an imaginary but convenient break between polytheistic myth and monotheistic purity, he challenges a whole roster of the 20th century’s great Jewish thinkers, including Gershom Scholem, the most famous student of Jewish mysticism. Scholem and others have maintained that Kabbalah was a mysterious outburst of a mythology that had been cut off and repressed in mainstream Judaism. But, Fishbane argued, if its myths were truly alien or obscure, Kabbalah could not have won the massive and widespread acceptance that it did.

He added that accepting the theory of a major cultural break would make it “difficult to understand how theological material of such a presumably alien and dangerous nature could have entered the conservative mentality of rabbinic Judaism.” He noted that it would be equally difficult to understand how such material could have been thoroughly absorbed into Jewish ritual life or presented publicly as a sacred and primordial truth to both scholars and lay people.

The three Biblical myths and motifs central to the study have been studied in earlier articles of Fishbane’s, many of which were collected in his book, The Exegetical Imagination. These mythic themes are “divine combat,” such as God’s defeat of Leviathan; “divine wrath and sorrow,” God’s fearsome judgment on Israel or the nations and his repentance for that judgment; and “sympathetic identification,” in which God imitates human acts such as suffering or exile.

“Myths are a positive and vital feature of monotheism and are the carrier of some of its most powerful and poignant theological topics,” Fishbane argued. This most recent work emerges as part of his overall project-first laid out in his book, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel, which seeks to recover the inner principles and ideas that vitalize Scripture and Judaism. In the process he has sought to develop a series of methodological principles that guide his own work and provide tools which other scholars may adopt, refine or disagree with.

Trained in Semitic languages, biblical studies and Judaica, Fishbane has written about the ancient Near East and biblical studies, rabbinics, the history of Jewish interpretation, Jewish mysticism, and modern Jewish thought in such books as Text and Texture, Garments of Torah and The Kiss of God. His commentary on the prophetic lectionary (Haftarah) in Judaism has recently been published in the Jewish Publication Society Bible Commentary series. He currently is working on a commentary on the Song of Songs and a book on Jewish liturgical poetry.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)