Hajdu describes process of developing artful nonfiction, without creating ‘Moreau monster’

By Josh SchonwaldNews Office

David Hajdu, the 2003 Robert Vare Visiting Writer in Residence, is the author of Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn. |

“There’s an old joke,” said Hajdu. “What do you call a guitarist who can play only three chords? A music critic.”

But Hajdu (pronounced Hay-doo), who has written about virtuosos in jazz, folk, rock and other genres during his more than 30-year writing career, finds no shame in the fact that he writes about something he cannot do very well.

“I write about music because I love music,” he said. “I tell my students it’s more important to write about your passions than it is to write about what you know. Writing should have an aspirational quality.”

Hajdu, who is teaching in the College this quarter, hopes his 20 student writers aspire to create what is arguably a rarely achieved literary form–artful nonfiction. In his class, “The Art of Nonfiction Literature,” the author of two award-winning works of literary nonfiction aims to show his students that through reportage, memory and history, nonfiction–so widely perceived as the straight recounting of fact in newspapers, colorless biographies and textbooks–also can be literature.

Hajdu’s class is primarily a workshop–his students will produce a 4,000-word piece of nonfiction this quarter, but it also has an extensive reading list, ranging from such memoirs as Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That and Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, to more recent works, such as Jonathan Raban’s Badland and Kathleen Norris’s Dakota. Hajdu also strongly encourages his students to read The Art of Fact, a historical anthology of nonfiction. “Nonfiction writers should realize that they’re coming out of a rich tradition.”

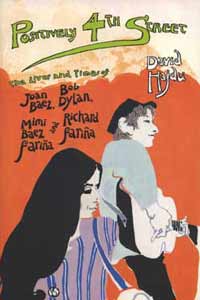

The first writer in residence to specialize in the arts, Hajdu is the author of Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn, which Will Friedwald of The New York Times Book Review called, “one of the finest biographies yet written about a jazz musician.” His second book, Positively 4th Street, an account of how four young people in New York’s Greenwich Village–Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Mimi Baez Farina and Richard Farina–gave rise to the folk music explosion of the 1960s, was noted by Jonathan Yardley of The Washington Post as “one of the best books about American music.”

In your first class, you told your students you believed we’ve entered a golden age of nonfiction. What do you mean by this?

I know I’m stepping onto thin ice in making a pronouncement like this, and I may look at this in 10 years and say I was foolhardy, but there are signs that we’re living in a great age for nonfiction. Others have said this before me. James Atlas, writing several years ago in The New York Times magazine said many of the most interesting books to be published are nonfiction. It’s not that novels or fiction have diminished, it’s not that fiction is any less legitimate or less artful than ever. But it’s that nonfiction seems to be fulfilling more of its literary potential. Writers like Luc Sante, Alexandra Fuller, Jonathan Raban, Robert Anasi and others are doing beautiful and poetic nonfiction.

David Hajdu’s newest book, Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Farina and Richard Farina, was noted by Jonathan Yardley of The Washington Post as “one of the best books about American music.” |

I think it is well-founded. A lot of what passes for nonfiction is a freak of crossbreeding, like a Moreau monster. People think, ‘Now, I can apply my imagination. Now, I can invent interior monologues. Now, I can apply imagination to a description of a scene or an event.’ It’s a bastardization of literature; it’s a bastardization of journalism. As a result, it’s inferior as both. And I think we may well continue to see more of that kind of nonsense, history with imagined and reconstructed events; it’s largely bogus.

Lush Life was unusually successful for a first book, winning awards and critical acclaim. How do you account for that rookie success?

I had done my apprenticeship in secret. I did all sorts of things without my name on them–some serious, some junk. I wrote and published two novels under a pseudonym. I wrote columns for women’s magazines under other names. I ghost wrote a psychology book–I won’t tell you the name of it. I wrote directions for a golf board game. All the time I was learning how to be adroit with language. In those two novels, I learned how to tell a story. And I learned over the first hundred pages, what it took in me, what it takes in a person to do something so big. That’s why my first book doesn’t read like a first book. My first book is really my fourth book.

For many years you’ve described yourself as having been “evangelical” about your art, literary journalism. How did this need to evangelize come about?

I worked at Time Inc. for 10 years as an editor. I didn’t write, I just edited. But I became a sort of Pentecostal of the literary tradition there. A writer, 22 years old, would interview Quentin Tarantino and think, ‘Oh my god, I’m a pioneer.’ I would say, ‘be a pioneer, invent something new, but don’t do the same old thing and think it’s new. Understand the tradition, so you have the grounding to invent.’ I would make copies of Lillian Ross’s piece about John Huston and The Red Badge of Courage and say, ‘this can be done very well. Here’s an example of how it was done really well–50 years ago.’ I’d encourage writers to build on that tradition, but break out of that tradition. And we did do things at Time during those years. We broke out of the narrative tradition. We looked at subjects in a sort of post-narrative, post-linear way. Instead of doing one 5,000-word story on a subject over the course of 10 pages, we would give that same subject 20 pages, but do 40 stories. Every angle was covered with charts and diagrams and odd things and pictures. Graydon Carter and Kurt Anderson were doing similar things at Spy Magazine. It was an interesting time in mainstream journalism.

As a teacher of this art, is it more difficult to teach someone who has a background in journalism or in literature?

There are problems with students coming out of each world. I find writers who come out of fiction just terrified to do an interview or pick up the phone. They’ve learned to apply their imaginations, but they haven’t learned these other skills, like unearthing facts that illuminate deeper truths. I find problems in the ranks of working writers as well. Historians, for instance, who are doing recent history from the secondary sources who haven’t visited the location they’re describing, walked the streets they’re describing, or bothered to see if witnesses of the events they’re describing are alive and picked up the phone to call them. I’m appalled to read about events in the ’30s and ’40s, where writers didn’t wonder, “what if anyone who was there that day is available?” By the same token, I read works of journalism in which it is very clear that the writer hasn’t read any history or doesn’t understand the discipline of history.

Tell us about your current work, which you discussed in a recent lecture, “The Read Menace,” at the Franke Institute for the Humanities.

I’m writing about the world of comic books, something I knew virtually nothing about before. I’m interested in disreputable art forms, and for a long time, jazz was a disreputable art form. It will be a work of history about a period in the late ’40s and early 1950s when comic books had a profound influence on mainstream American culture. They were the most popular form of entertainment in the country, more popular than movies, television, books and radio. Between 80 and 100 million people were buying comic books, including adults, and they weren’t just comics about superheroes. It’s a largely forgotten period. I don’t understand it myself, but I’m trying and am doing a lot of research while I’m here, and that is the fun part.

![[Chronicle]](/images/sidebar_header_oct06.gif)