Law professor offers story of British naval captain and penal colony he supervised as parable for today’s prison system

Peter SchulerNews Office

|

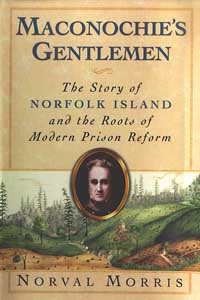

Norval Morris has found an island in the South Pacific in 1840 to be an unlikely but rich source of insights into the present-day U.S. prison system. Morris, the Julius Kreeger Professor Emeritus in the Law School, has woven fact and fiction in his latest book, Maconochie’s Gentlemen: The Story of Norfolk Island and the Roots of Modern Prison Reform (Oxford University Press). And his account of a brutal British prison that was briefly transformed into a model of rehabilitation has won critical praise.

Morris used historical records, letters and biographical materials as the foundation for the fictional account of a retired British naval captain, Alexander Maconochie, who volunteered to become superintendent of what was then England’s most harsh and remote penal colony.

“The story is based on facts and shaped by intuition and speculation,” Morris said. He tells the story through the fictional voices of Maconochie, his sympathetic but rebellious daughter and a Norfolk Island convict. As a native of New Zealand who studied law in Australia, Morris also drew on his own knowledge of the South Pacific.

The “gentlemen” referred to in the title are the ex-convicts who were rehabilitated through the Maconochie prison experiment. Norfolk Island was home to more than 2,000 convicts living, as Morris described, “crowded together in bug-ridden cells and dormitories, fed in a shed, which could hold about half their number, the rest eating outside proximate to a stinking communal privy, their food lifted to their mouths by their fingers, since knives and forks were prohibited, lacking sufficient water regularly to wash themselves or their drab clothes, and compelled to try to clean themselves without paper after defecation.

“In some significant ways the Norfolk Island penal colony was not that different from prisons today,” Morris said. “The occasionally sadistic guards, like the prisoners, would prefer to be elsewhere; there is the gap between the formal prison authority and the real one, where gangs hold sway; the ways in which prisoners inevitably secure forbidden substances; and authority is accused of being ë#145;soft on crime’ when reforms are begun.”

Maconochie believed “banishment to Norfolk Island was punishment enough,” Morris said. “Subjecting the prisoners to further torment would only render them more bitter and broken.”

The retired naval captain rewarded good behavior with privileges, using what he called the “marks system.” The marks were credits that reduced prison-time served, based on good behavior. During his four-year leadership, Maconochie imported musical instruments, set up a library where books were read to the illiterate, permitted the use of eating utensils and allowed the convicts to plant gardens. He drastically reduced corporal punishment, fostered vocational training, and offered increased privacy and independence for those who earned sufficient marks. The methods were a success, and Norfolk Island was transformed into a peaceful and orderly settlement. For his efforts, Maconochie was derided by senior government officials in England and ultimately dismissed.

Morris, who has written numerous books and articles on prison reform in his distinguished 53-year legal career, offers the Maconochie story as a parable with lessons for today’s system of incarceration, which he views as highly flawed. “The public dialogue remains shatteringly superficial and does not seriously address either the social utility of incarceration or the rights of the individuals who are imprisoned. The debate is largely confined to whether deterrence or rehabilitation is the more powerful technique for reducing crime,” Morris said.

“That capital punishment is still carried out in this country is astonishing in light of what is now known about its failure to reduce homicides and its inevitable risk of executing the innocent. And all the other policies in vogue, like ë#145;three strikes, and you’re out,’ ë#145;zero tolerance,’ and super-max prisons, among many other harsh measures, have repeatedly been shown to do more harm than good.”

After Maconochie’s departure in 1844, the penal colony reverted to its old ways and all of Maconochie’s policies were abandoned. His successor’s administration, as described by a contemporary observer, was “marked by utter incompetence and debasing cruelties.” The daily cruelty to the prisoners returned, as did floggings and hangings.

In 1855, the convict settlement was closed, not from a recognition of its brutality but because of the high costs to resupply it. The island lay uninhabited until 1865 and then became the home of the children and grandchildren of the Bounty mutineers, when the English government moved them from Pitcarirn Island.

The lush and temperate island is now a tourist destination. Mixed with the usual resort diversions are historical entertainments that depict the hard world of the prison colony and the idyllic world of the Bounty offspring. Rarely mentioned are the extraordinary four years when Captain Maconochie created a model for the treatment of prisoners that is rarely found today.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)