Renaissance Society of America will honor Bevington for editorial work on dramatic texts

By Seth SandersNews Office

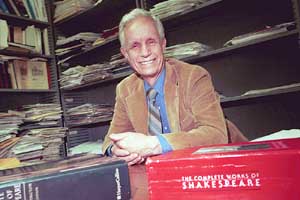

David Bevington |

Having edited the complete works of William Shakespeare as well as a sequence of key plays in medieval and Renaissance drama, David Bevington naturally has a stake in how these texts are understood.

In his scholarship, Bevington, the Phyllis Fay Horton Distinguished Service Professor in the Humanities, has been engaged with all aspects of medieval and Renaissance drama, from the fundamental philological work of making the texts available for theoretical discussions about where and whether the text of the play exists, to the most personal connection with their meanings.

For his editorial accomplishments, the Renaissance Society of America will honor Bevington at its annual meeting this month with its Paul Oskar Kristeller Lifetime Achievement Award. It will be the first time that this multidisciplinary group, which studies every aspect of the European Renaissance, will present the honor to a scholar in English literature.

Although Bevington draws from earlier editions and consults with other experts, the day-to-day work and final decisions are his. “All the other Shakespeares are done by committee; mine has the limitation and the advantage of being done by one person. The introductions are all mine, the editing is from one point of view. Though there are many consultants, such as George Williams at Duke University and Barry Gaines at the University of New Mexico, to whom I’m very grateful.”

To his credit, Bevington has edited The Necessary Shakespeare, a collection of the most-taught plays, and the Bantam Shakespeare, a series of paperbacks that offer information about the sources Shakespeare used in writing his plays. In these books, one can see what Shakespeare drew on when he wrote Othello, for example. Several of Shakespeare’s plays on classical subjects were taken out of Plutarch’s Lives.

In at least one such play, Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare copied his source with borrowings that today would qualify as plagiarism. But, as Bevington explained, Shakespeare or Chaucer’s ideas of authorship differed from ours.

The Elizabethan version of “author” was more like what today would be referred to as “compiler” or “maker;” dramatists were in the position of taking material from wherever they saw fit and dramatizing it, explained Bevington. Shakespeare knew how to transform such borrowings in ways that give them a dramatic vitality not found in the original.

Currently, Bevington is “doing a little book called Shakespeare,” attempting to describe how Shakespeare appeals to us so remarkably by his ability to see the whole cycle of human life––from childhood rivalries and courtship to success in a career, troubles in marriage, disillusionment about sexuality and political life, skepticism, midlife crisis, old age and finally the end of a writing career. Two years ago, he described how “Shakespeare Faces Retirement” as his presentation for the annual Ryerson Lecture.

“Facing retirement myself in three years, I wanted to ask what the late plays can perhaps tell us about Shakespeare’s own frame of mind as he came to the end of his work in the theater. There’s some evidence that Shakespeare was not in good health, was running out of steam and wanted to end strongly in The Tempest. It’s extraordinarily short and perfect. His colleagues who edited his play for the big folio edition of 1623 put The Tempest at the head of the book and took special care preparing the manuscript to make sure it was especially well printed.

“One can hear in Prospero’s voice a certain amount of anger and fear of death, with the result that he sounds like a very patriarchal and domineering father. He deceives and makes to suffer the Italian party that’s arrived on shore. His autocratic way of managing their lives gives us a useful paradigm of what a dramatist does––puts his characters through hell. To do so poses an immense burden for him, since it’s so patently managerial. Yet it’s important to see that Prospero has a moral purpose in what he does.

“The play is not openly didactic, but Shakespeare does seem to see a way in which his theater should attempt to improve the lot of the human race. Ariel, who represents something like divine inspiration, clearly sides with Prospero in what he does. He sees, as we do, that Prospero is playing God. And part of his function as such is to lead erring human beings like Alonso to a better understanding of themselves through atonement and eventual forgiveness. Weirdly, while Prospero is playing God, he’s also lying.”

Bevington now is proofing The Norton Anthology of English Renaissance Drama, to be followed by The Complete Works of Ben Johnson. While these projects cohere perfectly with his past, it is Bevington’s earlier track record that earned him the lifetime achievement award.

His anthology titled Medieval Drama brought a neglected but crucial spectrum of theatrical history to the forefront of scholarship. The volume starts with church liturgy, which Protestant scholars dismissed as an artifact of the primitive Catholic mind. Despite the fact that this is where Renaissance drama took root, medieval drama was not taught when Bevington was in graduate school. “Back then, there were no women––or Catholics––on the faculty. Now there are about 2,000 medievalists at the annual meeting in Kalamazoo.”

The way in which Bevington made the journey from medieval drama to the Renaissance––editing everything in his path––led to his upcoming recognition from the Renaissance Society of America.

“It’s been a wonderful education for me, too. I love the fact that I get these plays in my bones so I can teach all of them with such joy and familiarity. It’s been an exploration––I got into medieval because I wasn’t happy with the way the transition to the Renaissance was presented: where the heck was great drama of the English Renaissance coming from?”

In his career at Chicago, he’s been able to continue that path to the present. Of his collaborative teaching of the history of drama with Nick Rudall, Associate Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures and the College and Founding Director of Court Theatre, Bevington said: “Teaching with him has been wonderful that way, from the Greeks on down to Stoppard and Pinter. I owe to Nick a lifetime of education in the history of European theater through the plays he has staged at Court, during the many years when I had the privilege of serving on the board of the Court Theatre, and occasionally helping out backstage.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)