Classic Chicago: A non-traditional approach to studying Greek, Roman antiquities

By Seth SandersNews Office

Danielle Allen, Associate Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures and the College, received the coveted MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant last year. |

In a university famous for its devotion to long-lived texts, stereotyped as the works of “Dead White Men,” the Classics Department is the standard bearer for the longest dead and most traditional. One has images of men in tweed suits suffering through impenetrable verses of Pindar over a glass of port in some dusty wood-paneled room. The grueling Pindar workouts and the dusty wood-paneled rooms remain, but everything else is new.

It is a pleasant shock to see how much fun Danielle Allen’s students seem to be having. It is inspiring to find Allen and Martha Nussbaum arguing that their Tragedieans and Stoics can tell us things about our own lives and politics that may not only be more beautiful but more relevant than what we read in the newspapers. And it is downright fascinating to hear Christopher Faraone, an expert on ancient love magic, talk about overturning an idea treasured by Friedrich Nietzsche and modern rock critics––the polar opposition between Apollo and Dionysus.

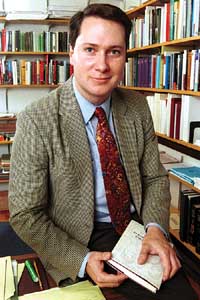

Faraone, Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures and the College, recently stepped down as Chairman after presiding over a departmental renaissance. A series of rising scholars with widely varying strengths came to Chicago; the main thing they have in common is their interest in fresh approaches and commitment to interdisciplinary work (most recently highlighted when Allen, Associate Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures and the College, received the coveted MacArthur fellowship, which rewards boundary-stretching research).

Shadi Bartsch, Chair and Professor of Classical Languages & Literatures and the College, who succeeded Faraone, is currently writing a book titled The Mirror of the Self: Sexuality, Self-Knowledge, and the Gaze in the Early Roman Empire. The book exemplifies the vital intersections the department is finding between ancient and modern concerns.

Shadi Bartsch, Chair of Classical Languages & Literatures, describes it as “a department famous for its philological rigor, for its expertise in ancient philosophy and literary criticism, and for its innovative application of social science methodologies to the study of ancient Mediterranean history, religion and culture.” |

Bartsch’s book looks at “the relationship between three fields that are disparate today but were much more closely linked in antiquity: optical theory, ethics and the workings of love.” Since at least Plato, western philosophers often have understood knowledge as a kind of vision. As in Greek, in English, too, the vocabulary of seeing and knowing is linked. Simply consider the phrase, ‘I see.’ Bartsch cites the famous “parable of the cave” from Plato’s Republic: “Here the ascent of the soul to the contemplation of pure wisdom that is, to the vision of the Good, for which Plato uses the sun as a metaphor, is couched in the vocabulary of blindness and seeing.”

But, Bartsch said, if you look at what the Greeks really said about vision, they often describe the optical experience itself as tactile––when you see, it is because tiny objects touch the eye or are emitted from it. Not only this, but also these objects “often are described as having a potentially sexual effect upon the object of sight, which can be penetrated and in some cases even aroused by their action. So it is that the ancient Greek novelist Achilles Tatius, for one, claimed that looking at the beloved works in the same way as sex. In both cases, bodily penetration and arousal are involved.”

This led Bartsch to ask, “What is the relationship between the philosophical and the erotic paradigms for vision in antiquity?” And today, when we completely separate vision from touch, how does this affect our “thinking about the acquisition of ‘objective’ knowledge, the boundaries of our bodies, the relationship of passion to science?”

Christopher Faraone formerly led the Department of Classical Languages & Literatures as Chairman. During his tenure, Faraone presided over a departmental renaissance. |

Speaking as Chair, Bartsch described the department’s claims to academic distinction as “a department famous for its philological rigor, for its expertise in ancient philosophy and literary criticism, and for its innovative application of social science methodologies to the study of ancient Mediterranean history, religion and culture.” She has written that in the course of the last decade, “in both our research and graduate teaching we have managed to enhance our department’s pre-eminence in the traditional areas of our discipline, while at the same time adding enormous new depth in our coverage of more recent theoretical developments.”

Yet for undergraduates, the Classics Department is most notable for its teaching. A trio of young scholars––Allen, Bartsch and Laura Slatkin, Associate Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures and the College––has consecutively won Quantrell Awards for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching, building on an already strong track record that includes James Redfield, the Edward Olson Distinguished Service Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures and the College; Peter White, Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures and the College; and Richard Saller, Provost and the Edward L. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor in History, Classical Languages & Literatures and the College, among other recent winners of the award.

“Teaching is something we worked really hard at under my tenure as Chair and John Boyer’s time as Dean of the College,” said Faraone. “We think hard about our teaching in the College. There’s always the danger at a research university of people thinking they’re there to research, and if they happen to bump into an undergrad, well, that’s a casualty of the job.”

Jonathan Hall, Associate Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures, History and the College, is the youngest scholar ever to win the Charles J. Goodwin Award for Merit from the American Philological Association for best book in the field. |

Instead, he said, “Our labor is divided into a third teaching, a third research and a third administration, because it’s a faculty-run university. We have three faculty meetings a quarter, and two years ago we decided that one of these would be devoted entirely to College matters. It’s gotten us to focus on College teaching. Before that we really just focused on the grad students.”

The efforts of Faraone, Bartsch and their colleagues have begun to pay off. “In most areas we see ourselves competing with the very top departments, like Princeton and Berkeley,” said Faraone. This impression is confirmed by conversations with graduate students like Fanny Dolansky, a Ph.D. candidate in Roman social history, whose work focuses on sex, gender and the family. She was able to choose from a number of top graduate programs, but what sold her on Chicago was “better faculty and a warm department. There are a lot of young faculty who are energetic, enthusiastic and generous with their time,” she said. According to Dolansky, the pace of research is so fast that graduate courses are generally offered only once, as faculty move on to new topics.

Chicago’s rising status encompasses not only attracting the most promising faculty and graduate students, but also achieving recognition for meaningful work. Jonathan Hall, a new Associate Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures, History and the College, is the youngest scholar ever to win the Charles J. Goodwin Award for Merit from the American Philological Association for best book in the field. His book Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity, for which he won the award, provides a sober look at an important but sticky topic––the question of what it meant to be ethnically Greek. Hall’s colleague James Redfield explains that Hall “took a contentious subject and put it in order. The Germans in the 19th century were very into the Dorians––they thought they were the Dorians, in opposition to the Ionians. Hall looked at what the Greeks actually said and found what you often find when you really look into these things. It was a lot more complicated and unlike us than we’d thought. This is what doing history is all about.”

Hall and Allen are both graduates of Cambridge University, which, Faraone said, “has had a long and productive interaction with Chicago.” The department also has changed a lot in the last 30 years. “Prior to the 1980s we had a tradition of being a very old-school and rigorous philology department,” Faraone explained, “but in recent years there has been more and more focus on social and cultural history and different kinds of interdisciplinary work.” But they have managed to do this without sacrificing the central emphasis on language, he said.

“The Journal of Classical Philology is still a center of linguistic and textual criticism. Scholars here, like Helma Dik (Assistant Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures and the College), a classicist with a strong background in linguistics, continue that. And through our connections to the Divinity School and the Oriental Institute we continue to be strong in religious studies in collaboration with scholars like Bruce Lincoln (Caroline E. Haskell Professor in the Divinity School), James Redfield, J.Z. Smith (Robert O. Anderson Distinguished Service Professor in the Humanities and the College) and David Martinez (papyrologist and Associate Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures and the College) and myself.”

Another surprising recent turn at Chicago is the confluence of interests around the Roman writer Seneca. Considered an important Stoic philosopher and playwright, a poet, and author of many letters, up until 10 years ago, Seneca was not taught much. “A couple of years ago, I sent out an e-mail asking about what courses people wanted to teach, and three people independently came up with his name,” Faraone explained. Daniel Ray, a former Professor in Classical Languages & Literatures; Martha Nussbaum, the Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics in the Law School, Philosophy, the Divinity School and the College and an Associate in Classical Languages & Literatures; and Glenn Most, Professor in the Committee on Social Thought and the College, all wanted to teach Seneca.

Why Seneca? Why Chicago Classics? “It’s because this is where you can get social thought, classics and philosophy together,” said Faraone. “The reasons for contemporary interest are significant. First, the Stoics were less interested in academic discussion of abstracts and more concerned with carrying out the Socratic mission of how to live a better life. They focused on how-to, not theory. Second, with the growth of the Roman Empire, local citizenship stopped mattering and the subjects of the empire were beginning to wrestle with the idea of cosmopolitanism––what it means to be a ‘citizen of the world.’ This is why some modern philosophers like Nussbaum think we can profit by going back and reading the Stoics carefully, since they were reacting to circumstances similar to our own,” he said.

While these scholars are investigating the moral writings of a great and highly placed philosopher, another senior Chicago classicist is bringing back reports from a place many people do not even know exists. Redfield, son of the great Chicago anthropologist Robert Redfield, is completing The Locrian Maidens: Love and Death in Greek Italy, a study of the culture and religion of Epizephyrian Locri. A project he has been working on for 20 years, the book is an attempt to literally put Locri on the map––a far cry from the famous subject of his previous major book, Nature and Culture in the Iliad: The Tragedy of Hector. But, Redfield said, “The Homer book was my book about death, and this is my book about sex, and I’m feeling much better.”

In investigating the ritual and public role of women in Greek Italy, The Locrian Maidens takes a deeper look at the overall role of women in the Greek city-state, a subject so rich and difficult that “I only get to Locri halfway through the book,” he said. In the way it leads from ritual to romance to politics and back again, uncovering aspects of life both intimate and public, Redfield’s book seems quintessentially Chicago.

As for his own work, Faraone has two books in preparation. The first is a study of the ancient Greek magical incantation as a type of poetry.

The second attempts to re-examine the longstanding Nietzschean opposition between the cool-headed, sunny Apollo and the wild Dionysus, god of wine and dark manias that erupt from beneath the earth and established order. His book will expose an anti-Romantic, anti-Nietzschean aspect of Apollo that was quite popular in early Greece, especially in the Aegean and the cities of Ionia. This Apollo–– who appears mightily in the first book of The Iliad–– is not as the god of light and reason, but rather the bringer of plagues, capable of orgiastic feats of destruction.

This darker Apollo has long been known in classical literature, but often passed over in interpretations of the god’s role. “He’s represented in this bloody way at the beginning of The Iliad and the end of The Odyssey––in fact the goriest scene in The Odyssey. The scene that ends it is the massacre of the suitors, which occurs on the day of a festival dedicated to him. And in some ways it is really a giant sacrifice to Apollo by means of his favorite weapon––the bow.”

Faraone said that the work he is interested in uncovers great diversity in Greek religion. After many years of working with ancient material, he has developed a discomfort with such general statements as: “X is a feature of Greek religion,” or “The Greeks believed Y about their gods.” In fact, he said, “there are many, many different religious and cultic traditions in ancient Greece. Once you get to the graduate level of study, you have to give up this unitary category of ‘Greek religion’ and look at each city one at a time.”

He said the story of his work is one typical of Chicago faculty and graduate students in the Classics Department. “Many of us come here intent on studying ancient Greek and Roman literature, but then we end up venturing off into something really different or seeing the canonical texts in a completely different light.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)