Microprobe aids in new collaborative research on chromosomes

By Steve KoppesNews Office

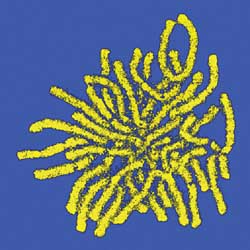

This false-color image of the distribution of calcium in the chromosomes of a deer, was obtained using secondary ion mass spectrometry with the University’s high-resolution scanning ion microprobe. Such images are revealing new details about cellular reproduction. |

Scientists in Physics and Medicine are glimpsing previously unseen details of cellular reproduction with a high-resolution scanning ion microprobe invented at the University by Riccardo Levi-Setti, Professor Emeritus in Physics, the Enrico Fermi Institute and the College.

Since the 1960s, scientists have suspected that positively charged metal atoms, called cations, play a key role in helping chromosomes maintain their structure while carrying out the chemical instructions necessary for cellular reproduction. Now they have the images to prove it.

The images were published in a cover story in the Dec. 10, 2001 issue of the Journal of Cell Biology. The Harold and Leila Mathers Charitable Foundation soon after awarded Levi-Setti a three-year, $605,000 grant to further the research.

A Chicago team has for the first time detected and mapped the presence of calcium, magnesium, sodium and potassium on chromosomes. The team’s experiments suggest that calcium plays an especially important role in regulating chromosomal proteins that control cell division.

Levi-Setti’s co-authors were Reiner Strick and Pamela Strissel, formerly Assistant Professors in Medicine, and Konstantin Gavrilov, Research Scientist in the Enrico Fermi Institute. Strick and Strissel are now at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg.

Levi-Setti developed a prototype of the high-resolution scanning ion microprobe that made the research possible in the 1970s. In the 1980s, he built a second-generation instrument in collaboration with Hughes Research Laboratories in Malibu, Calif. The instrument enables researchers to map the chemical composition of any material, from biological samples to metal alloys, at high-spatial resolution.

“This opened up tremendous opportunity to do interdisciplinary research,” Levi-Setti said. “You can take materials from any field of study and pretty much tell the details of composition.”

Researchers using standard X-ray techniques are unable to image cations without destroying the proteins or DNA structures contained in the sample. Levi-Setti’s technique also destroys the specimens, but it takes advantage of the damage.

“We peel off layers of material a little bit at a time. It’s like peeling an onion,” he said. “We are collecting and detecting what we take off. In the end you have destroyed the specimen, but you get all the information you possibly could.”

The Chicago team’s experiments showed that calcium, acting in concert with certain proteins, helps chromosomes stay tightly packed with DNA, the blueprint of life. Human cells, which measure a small fraction of the width of a human hair, contain more than two yards worth of DNA. “That’s a compaction of over 10,000-fold,” Strick said.

The positively charged calcium neutralizes the negatively charged DNA, thus eliminating the latter’s antagonistic forces during compaction. Calcium also seems to play a critical role in regulating the protein topoisomerase II, which untangles DNA during compaction by cutting it, moving it around and fusing it together again.

The latest findings are the culmination of a five-year collaboration between Levi-Setti and his medical school co-authors, who worked in the leukemia laboratory of Janet Rowley, the Blum-Riese Distinguished Service Professor in Medicine, Molecular Genetics & Cell Biology and Human Genetics.

The study’s immediate implications apply mainly to cell biology, Strick said. But leukemia researchers may also someday be able to build on the study’s findings regarding calcium’s regulatory influence over topoisomerase II. Scientists may eventually be able to exploit calcium’s influence on topoisomerase II to disrupt cellular reproduction.

“Topoisomerase II is the main target for chemotherapy,” Strick said. “Without topoisomerase II, there’s no cell division. No cell division means your cell dies.”

Strick and Strissel will continue their collaboration with Levi-Setti from across the Atlantic. Next the team plans to further quantify the concentration of potassium and sodium on the chromosomes. They also will chart any fluctuations in the amount of potassium, sodium, magnesium and calcium that may trigger the cell-division process from one stage to the next.

Tackling such problems with his scanning ion microprobe has made it difficult for Levi-Setti, 74, to truly retire. “I cannot quit, because when you have a machine like that, it’s very hard to let it go,” he said. “You keep seeing more things that you can do.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)