Graduate student chronicles Hyde Park’s colorful past

By Josh SchonwaldNews Office

Max Grinnell, a graduate student in the School of Social Service Administration, is the author of Images of America: Hyde Park, Illinois, a book about the neighborhood’s pre-urban renewal days. |

Hyde Park’s colorful history is an important part of any orientation to the University. Newcomers quickly learn that the neighborhood once was a wild, notorious place, especially 55th Street. A seedy, crime-ridden strip lined with more than 20 taverns and nightclubs––including legendary jazz hot spot the Bee Hive––55th Street was a sort of Bourbon Street of the South Side. And then came the 1960s and the Hyde Park-Kenwood Urban Renewal Project, which radically altered much of Hyde Park, including 55th Street.

After hearing stories of 55th Street’s raucous days, and then experiencing the suburban-like calm of contemporary 55th Street, Max Grinnell (A.B., ’98), like other Chicago students, wondered, “What happened?” Looking at the tidy townhouses, Grinnell said, “It was hard to believe the stories.”

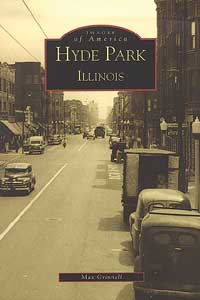

Eight years after arriving at Chicago, Grinnell, now a student in the School of Social Service Administration, has completed the first visual history of pre-urban renewal Hyde Park. The 128-page book, Images of America: Hyde Park, Illinois, includes more than 100 photographs of the neighborhood and surrounding areas in Woodlawn. It is an attempt, he said, “to give people a real sense of the look and feel of pre-urban renewal Hyde Park.”

|

Previous works have dealt with the neighborhood’s evolution, but Grinnell’s book is unique because it not only is a visual history, but it offers new insights into the University’s role in affecting the controversial urban renewal project. Information about the project, the nation’s first to be federally funded, remained confidential for three decades, but now has become publicly available, Grinnell said. Citing records archived at the University, Grinnell included new information about the University’s land-buying strategies and political efforts in Hyde Park and Woodlawn.

Grinnell, who concentrated in history and geography as an undergraduate student, said his interest in Hyde Park’s history began, in earnest, after he became involved in community activities, such as working as a polling volunteer at the Sinai Chapel during the 1996 presidential campaign. Through contact with members of the community unaffiliated with the University, he discovered that, even 30 years later, passions still flared over urban renewal. People had such differing views, he said. Some romanticized Hyde Park’s past, while others enthusiastically supported the changes brought about by urban renewal.

Grinnell’s effort to recreate Hyde Park’s past began in the summer of 2000.

The biggest challenge, he said, was obtaining photographs. He had notices published in the alumni magazine, asking members of the alumni community to send him pre-urban renewal photos. He also mailed letters and called more than 50 local churches and community organizations. Only a handful of alumni responded and only a few community organizations had photos of that era. The majority of the photos and maps used in the book came from archives at the Joseph Regenstein Library, from the City of Chicago archives at Harold Washington Library and from several local residents.

These documents reveal some surprising aspects of the past. One photo, for example, shows an advertisement for the Compass Bar, former home of the Compass Players, with an exhortation in ancient Greek. A pre-renewal map from the Sociology Department plots concentrations of Hyde Park’s juvenile delinquents. And a series of photos show startling views of Woodlawn, particularly the crowded intersection of Cottage Grove and 63rd Street.

Woodlawn once was the South Side’s largest retail district and home to the nine-story Illinois Central Railroad Station, which was ground zero for thousands of black migrants arriving from the South. Moreover, contrary to popular belief that 55th Street was the area’s entertainment hub during the 1920s, 63rd Street, with four major theatres, was the true hub, Grinnell said.

While the book is primarily intended as a visual document, Grinnell also probed primary documents––land-use maps, University archives, meeting minutes and logs of real estate purchases––to piece together a narrative of land-use change in the area. Currently, he is creating a series of maps documenting this land use change and parcel ownership.

The biggest surprise in his research, said Grinnell, was learning about the University’s interest in southwest Hyde Park. Previous research suggested the University’s primary interest was in removing blight from the area around Lake Park Avenue and 55th Street. Grinnell’s research suggests otherwise. Former University Trustee Harold Swift was very concerned about the one section of Hyde Park that extends from the intersection at 57th Street and Ellis Avenue to Cottage Grove Avenue on the west, and to 59th Street on the south. In one document, in fact, he warned ominously: “I know we are going to be sorry if we don’t do something about reclaiming properties from 55th to 59th.”

If there is any single lesson Grinnell believes he has learned from his study of the urban renewal effort, it is the importance of getting the community involved. Grinnell believes much of the acrimony in Hyde Park toward urban renewal and the University stemmed from communication failures. “From today’s perspective, it was a heavy-handed approach to urban renewal,” he said. But, to be fair, Grinnell said, this wisdom is in hindsight. “This was the first large-scale federal renewal effort.”

Grinnell, a second-year graduate student in SSA who is currently interning at the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference, will discuss his book on Wednesday, Feb. 27, at the Seminary Co-op Bookstore, where the book is a best seller.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)