Then and now: Posters provide window to war-torn Afghanistan

By Seth SandersNews Office

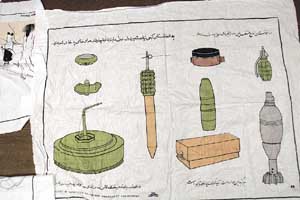

Mark Luce, a graduate student in Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations, (above) displays one of the many posters he’s collected from Afghanistan. The collection, which is a combination of paper posters and those printed on linen, such as the one below that shows a variety of landmines, has been donated to the Joseph Regenstein Library’s Middle Eastern posters collection. |

Americans have heard and read many horrible stories about the victims of the Tuesday, Sept. 11 terrorist attacks––first, the victims in New York City, then the refugees and victims of war in Afghanistan. People can readily identify with the victims of domestic terrorism, but it is more difficult to understand the experience of war for people in poor, faraway countries, especially when they speak languages many Americans had never even heard of before the events of 9/11.

A set of posters from Afghanistan from the 1990s and today, newly donated to the Joseph Regenstein Library’s collection of Middle Eastern posters, provides a unique window to that world. Collected by Mark Luce, a graduate student in Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations, the posters come from the exiled Afghan interim government of the 1990s, before the Soviets were driven out.

|

The posters communicate mainly through pictures, allowing an American viewer who is not conversant in Arabic or Pushtun to see the same thing an Afghan on the street would have seen in the late’80s or early ’90s.

The collection tells two very different stories. The first is told by a set of paper posters from the ’80s, many now torn. They are artifacts of a particular moment in Afghan history when the interim government was waging a vigorous propaganda campaign against the USSR. At a time when the radical Islamic and tribal warrior freedom fighters had gained the upper hand, the Soviet Union was still trying to maintain influence by offering a political compromise under the slogan of “National Reconciliation.”

|

One of the posters depicts a small child about to be run over by a hulking tank, emblazoned with the hammer and sickle. Below it is the slogan, “This is what the Soviets mean by National Reconciliation.” Other posters further disparage the Soviets’ offers or celebrate a liberated Afghanistan. The posters use bold colors, distorted caricatures and slogans drawn from the Koran and other sources. They radiate a clear, confident view of the world––friends and enemies, good guys and bad guys––as befits propaganda.

The second set of posters contains silkscreens, printed not on paper but on clean white linen. They were designed to be durable and washable, because they do not promote a particular government’s political line but address the more permanent problem of landmines. These posters were the official training visuals used by the UN landmine awareness campaign, which Luce designed and set into operation.

|

Most contain no words, just simple line drawings. They show what landmines look like, how they are triggered, how they can injure people and ways to avoid them. A few have written instructions in multiple languages: “Always look for signs of mines. Always mark the place you find them. Go get someone in authority.” They convey how ordinary life is different for children growing up in Afghanistan. One illustrates what might happen to a child who carelessly plays in a rural area. It bears the legend “You should always use public roads and not wander off.”

|

The posters have been donated to the Joseph Regenstein Library’s Middle Eastern poster collection, the largest in the United States. By collecting art, advertisements, notices and propaganda from the Middle East and adjacent regions, the collection helps to document the ideas, information and images that circulate among the people of these places.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)