Art of Mu Xin survives oppression of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution

By Carrie GolusNews Office

Mu Xin, Spring Brilliance at kuaiji, 1977-1979 |

During the Cultural Revolution in China, which lasted a decade (1966 to 1976), artists and intellectuals experienced a level of oppression that is difficult, even now, to comprehend.

In an attempt to survive during this period, artist and writer Mu Xin held low-profile posts and chose not to participate in official life. Even so, he was imprisoned three times, and more than 20 book-length manuscripts and hundreds of paintings that he had produced in secret were destroyed.

Under these conditions, most artists in China stopped creating art as self-expression. Mu Xin, however, continued to write and paint, even though he risked his life to do so. Remarkably, some of the work he produced during this period and immediately afterward has survived and will be exhibited for the first time at the Smart Museum of Art beginning today.

“Mu Xin is really a remarkable case,” said Wu Hung, the Harrie H. Vanderstappen Distinguished Service Professor in Art History and the College and co-curator of “The Art of Mu Xin: Landscape Paintings and Prison Notes.” Wu discovered Mu Xin in the early 1980s, after the artist had immigrated to the United States.

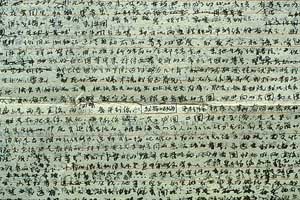

Mu Xin, Prison Notes, 1971-1972 (detail) |

“I was struck by the sense of natural beauty in his paintings, which draw upon Chinese and western classical aesthetics and also by the way he dealt with the trauma of the Cultural Revolution,” Wu said. “Other painters dealt literally with this trauma, while he internalized it and produced paintings that were so tranquil and so beautiful.” Soon afterward, Wu organized the first exhibition of Mu Xin’s work, a show at Harvard University.

Mu Xin was born in 1927 in Wuzhen, Zhejiang Province, to an wealthy, aristocratic family. Like most intellectuals in the late 1940s, he rallied around Mao Zedong’s vision for a new China, but he quickly became disillusioned. Between the Communist victory in 1949 and the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, his family was dispersed, imprisoned or killed and their estate destroyed.

For Mu Xin, the harshest period came during the Cultural Revolution, when, Wu explained, “every school, institute and factory had its own jail.” From 1971 to 1972, Mu Xin was confined in one of these makeshift prisons, an abandoned air-raid shelter in Shanghai. The conditions in these so-called “people’s prisons” were brutal; inmates were routinely denied food, medical care, exercise, even light.

One thing that was provided was paper, so prisoners could write the forced confessionals known as “self-criticism.” During his incarceration, Mu Xin stole 66 sheets of this paper, covering both sides with tiny, meticulous script and hiding his writings in the cotton padding of his prison uniform.

Mu Xin was certainly not the only prisoner who continued to do creative work in jail––but the fact that the “Notes” were never discovered and that he was able to leave with them intact, is almost miraculous. “I was jailed at exactly the same time,” Wu said, “and I also wrote novels and so on. You wanted to survive intellectually, not just physically. But when I was transferred to a camp, I destroyed my own work.”

The worn, ink-blotched, almost illegible sheets offer a powerful record of Mu Xin’s mental life in prison. “His writings have nothing to do with the real world. They are concerned primarily with fantasy,” said Wu. “They deal with philosophy, literature, ancient Greek art. He lived in harsh conditions, but he was not a slave to them; he was able to transcend them.”

After Mu Xin left China in 1982, several collections of his essays and poetry were published in Taiwan, where he was regarded as an undiscovered genius. His “Landscape Paintings,” 33 gouache and ink works, were created while he was under house arrest in the late 1970s.

Unable to work during the day for fear of discovery, Mu Xin produced the paintings under cover of darkness. “By day I was a slave,” Mu Xin has said of this period, “by night, I was a prince.”

These small works depict imaginary and real sites drawn from the tradition of Chinese landscape in painting and poetry; their titles evoke an ancient cultural past. At the same time, the influence of Western artists is clear, especially Leonardo da Vinci, whom Mu Xin has called “my early teacher.”

Many Chinese artists have struggled with the desire to reinvent modern art while remaining loyal to traditional Chinese subject matter, said Alexandra Munroe, Director of the Japan Society Gallery in New York and co-curator of the exhibition.

However, Mu Xin’s artwork “transcends the East-West polemic that has traditionally framed the debate,” she said. “The fact is that Mu Xin’s painting stands alone in modern Chinese art.”

As a counterpoint to the exhibition, the Smart Museum will present “Exposure: Chinese Photography from the Smart Museum Collection.” This show of six large-scale photographs and photo-based installations features prominent artists such as Rong Rong and Qiu Zhijie.

“The Art of Mu Xin” opens today with a gallery talk at 5 p.m., led by co-curators Wu and Munroe, and a reception until 8 p.m. The exhibition will remain on view through Sunday, March 31.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)