Structure of anthrax toxin offers clues to treatment

By John EastonMedical Center Public Affairs

|

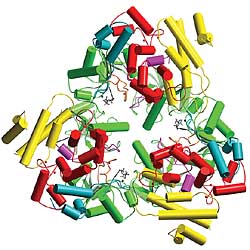

Researchers from the University and Boston Biomedical Research Institute have described the three-dimensional structure of edema factor, one of the three toxins that make anthrax so deadly. This finding, published in today’s issue of Nature, is a crucial step toward designing drugs to block the harmful effects of anthrax and perhaps other bacterial toxins.

Although antibiotics can kill the bacteria, anthrax produces toxins that can cause death even after the bacteria have been eradicated.

Since some forms of anthrax infection produce few symptoms until the disease is advanced, physicians need better drugs to counteract these toxins.

“Knowing the structure of edema factor and how it works allows us to design drugs that can block its effects,” said the study director, Wei-Jen Tang, Associate Professor in the Ben May Cancer Research Center at the University Hospitals.

|

Anthrax produces three toxins that work together. One, called protective antigen, allows the other two to enter target cells. The second, lethal factor, destroys cells of the immune system. When immune cells die they release inflammatory agents that can cause septic shock, leading to death. The structure for protective antigen was published in February 1997, and that of lethal factor in November 2001.

The structure of the third toxin, called edema factor because it causes fluid accumulation, provides the last piece of this pathogenic puzzle. Tang, his graduate student Chester Drum and Andrew Bohm of the Boston Biomedical Research Institute spent three years deciphering the structure of this deadly molecule and determining how it damages infected cells.

Edema factor can cause death by releasing fluid into the lungs or other infected areas. It makes lethal factor 10 to 100 times more potent and can disrupt immune function.

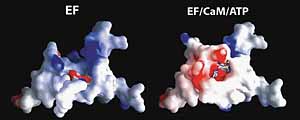

“This pathogen has evolved a very clever tactic,” said Tang. Edema factor alone is benign because one key section of the structure is incomplete. But when it connects with calmodulin, it changes shape and becomes a relentless version of adenylyl cyclase.”

Fortunately, the three-dimensional structure of edema factor appears to provide an ideal drug target. The active site, which mimics adenylyl cyclase, is a deep, narrow pocket that should be comparatively easy to block with a small molecule.

It also is very different from mammalian adenylyl cyclase, so there is little risk that the drug would interfere with the normal activity of this important enzyme.

At least two other disease-causing bacteria rely on a similar process: Bordetella pertussis, which causes whooping cough; and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which infects patients with cystic fibrosis and those with impaired immunity.

The work resulted from a collaboration between Wei-Jen Tang’s Chicago laboratory––including Drum, Shui-zhong Yan, Yuequan Shen, Dan Lu and Sandriyana Soelaiman––and Boston researchers Joel Bard and Zenon Grabarek.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)