Devices of Wonder: Extending the senses, intensifying reality has long history, which puts current issues in new perspective, says Stafford

By Seth SandersNews Office

Multiplying Spectacles, England, about 1650; Gilded metal and rock crystal, 3.8 x 8 cm (1 1/2 x 3 1/8 in.) Collection: Science Museum (by Courtesy of the Board of Trustees of the Science Museum), London |

An exhibition at the Getty Museum co-curated by Barbara Stafford, the William B. Ogden Distinguished Service Professor in Art History, has drawn rave reviews both locally and nationally. More importantly, it could focus several important debates about art, science and the impact of technology on society.

The exhibition, titled “Devices of Wonder,” puts a new spin on supposedly revolutionary things like “multimedia” and “virtual reality” by showing that interest in sense-enhancing and image-making technology dates back to the Renaissance and before. As a result, Stafford, who teaches in the Art History Department and the College, said, “You could as easily date hyper-reality to ancient Egyptian temple magic as to the ’80s.” But, she said, it goes far beyond a premonition of computers, movies or other familiar modern technologies. The real question, she said, is why “in different parts of the world and in various epochs, people insert a lens, mirror or monitor between themselves and their environment.” Stafford argues that the desire to extend our senses and intensify reality has a long history that puts current issues in a new light.

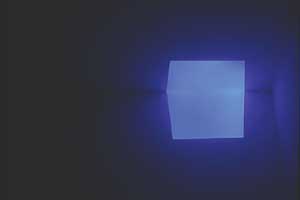

James Turrell (American, b. 1943); Catso Blue, 1967, Quartz halogen light; Lannan Foundation, Santa Fe |

Described by the Los Angeles Times as “both tremendously entertaining and profoundly cerebral” and by The New York Times as “taking reality for a loop,” the exhibition shows how projection devices, such as the camera obscura, removed the barriers between science and popular entertainment, and it explores multimedia objects, such as the Wonder-Cabinet, which combined mathematics, astronomy, communications and games as early as the 17th century.

The exhibition coincides with a new dispute that came to a head recently about whether great artists secretly used this technology in their paintings. At a New York gallery, artist David Hockney argued that such painters as Ingres had used the sort of lenses seen in “Devices of Wonder” to get their perspective and proportions straight.

Cornelius Jacobus von Oeckelen (Dutch, 1798-1865) Android Clarinetist, 1838; Mixed-Media, 189.2 x 67.3 x 76.2 cm (74 1/2 x 26 1/2 x 30 in.); John Gaughan Collection, Los Angeles |

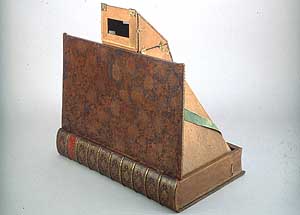

Whether or not the artists painted from projections, projecting devices revolutionized the mental worlds of artists and philosophers. This radical change in perspective went hand in hand with discoveries in optics because lenses allowed a viewer to project a three-dimensional scene onto a two-dimensional surface. Stafford sees a crucial analogy between these projectors and the Wonder-Cabinet, which projects a macrocosm into a microcosm: “compressing something into a box makes things more special than they are in and of themselves, producing a network where objects speak to each other and us across time and space. These early scientific instruments do the same thing as wonder cabinets, but capture images instead of solid objects.”

A second and more heated debate also has recently reached a turning point. Late last year, the University’s Cultural Policy Center sponsored a conference titled “Playing by the Rules: Video Games and Cultural Policy” (held at the Museum of Contemporary Art and the University on Oct. 26 and 27, 2001). There, experts from business, the sciences and humanities concluded that any attempt to assess the social impact and future potential of video games hinged on finding a historical context to understand how they differed from other games. What do they do that is the same as other modes of entertainment and education? What is unique and unprecedented about them?

Book camera obscura: Theatre de l’univers, France, ca. 1750; Wood, metal and glass; Open dimensions: 56.2 x 55.2 x 36.5 cm (22 1/8 x 21 3/4 x 14 3/8 in.) Getty Research Institute, Werner Nekes Collection |

By providing a broad and deep view of how visual simulations and automation have been used to entertain and educate for centuries, Stafford’s work in her books Artful Science and Visual Analogy serves as a corrective to the idea that this is something new and bewildering.

“There’s an enormous cognitive value in realizing that no media ever really die,” Stafford explains. “The Devices exhibition uncovers a whole history of visual thinking and practices that don’t just change our perception but our consciousness. You could suddenly project what you wanted to see––an amoeba, the circulation of blood in a frog. This made new social practices possible. There were lecturers and demonstrators and audiences, a whole series of intermediaries. The devices made profound religious and moral points. They could demonstrate the existence of other worlds through the microscope and telescope. The Jesuits of the 17th century used mirrors as metaphysical teaching devices. They could show how information is encrypted and decoded; in a religious age they could show physically that perception is skewed and that it has to be righted––they let people understand intangibles like God and perfection. Their lenses could both skew and rectify, reveal and conceal.

Lucas Samaras (American, b. 1936) Mirrored Room, 1966, 2.4 x 2.4 x 3 m (8 x 8 x 10 ft.); Albright-Knox Gallery, Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1966, Buffalo, New York |

Once people could use multiplying spectacles to see like insects, though multifaceted eyes, they realized that while they did not see the world this way, they could start to wonder who does. It is a way of wondering what it might be like to be truly different. This happened at the same time as the discovery of the New World. People were experimenting with other ways of seeing through other cultures, as well.

“It’s important to realize the deep linkages between old and new media: from the 17th- century sunspot-tracing machine to NASA photomontages of the moon done by the artist Michael Light. There’s a continuing desire that runs through this history, a desire to bring what is elusive and above us down to earth,” said Stafford. “We’re still here looking up, wondering about what’s beyond. The bottom line is that reality has long had a competitor. There were religious, social, intellectual and scientific reasons for the adoption and allure of these technologies that are still active today. We need to understand them.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)