Web site documents oral history of China’s Cultural Revolution

By Seth SandersNews Office

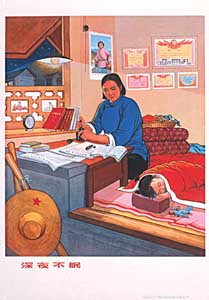

Still Awake in the Middle of the Night, unknown artist, n.d., Shanghai |

While we in the United States vocally debate a new outbreak of political violence, a worse outbreak lies buried in the recent past, almost completely unrecorded and undiscussed. Youqin Wang, Senior Lecturer of Chinese Language in East Asian Languages & Civilizations, created a Web site to return this terrible trauma to light. The Chinese Holocaust Memorial page http://www.chinese-memorial.org.htm, obscure in the United States but crucial to many in China, recently celebrated its first anniversary.

Perhaps the single largest example of silencing in recent history is the Chinese Cultural Revolution, a silence so large it could be described as deafening. In 1966 and again in 1968, on Chairman Mao Zedong’s direct orders, teenagers across the country turned on their teachers, taunting, accusing and then beating them. In a culture that had always revered educators and the old, many who were not beaten to death were driven to suicide out of sheer humiliation. Millions of people still remember these events, as participants, witnesses or victims.

Yet the traumatic violence of the Cultural Revolution is not part of recorded history in China. Wang says the violence of the Cultural Revolution, Western political ideas and pornography are part of an odd trio of officially forbidden topics for Chinese media. Yet Wang, in collaboration with hundreds of survivors, has made it her mission to help create written sources that can form the basis of a history of the Cultural Revolution’s violent events.

Wang originally learned Java script in a pioneering effort to put Chinese language teaching materials on the Web so students could read texts in Chinese, hear them pronounced at the same time and practice answering multiple-choice quizzes online.

Oppose Economism, Fandui Jingjizhuyi, proclaimed by the Shanghai Publishing Apparatus Revolutionary Rebel Headquarters, 1967, Shanghai |

She soon realized that her ability to create Web pages would allow her to publish material cheaply and disseminate it across national boundaries, evading the state censorship that still prevents Chinese discussion of the Cultural Revolution. She describes it as “the most severe tragedy in Chinese history” that has not been recorded in any written Chinese documents. The only potential records exist in the living memories of millions of survivors, witnesses and their friends and families.

Wang explains that even when the Chinese government officially recognized that the Cultural Revolution was a bad idea and began to cautiously repudiate it, starting in 1978, they only named a handful of elite perpetrators and victims. She said, “They condemned it but continued to control the discourse about it. If known, the cruelty of the Cultural Revolution would undermine the political system.”

Her site has become important to people affected by the Cultural Revolution, as the only place they could tell their stories. The Web page was constructed with the help of a survivor she met over the Internet who knew Web-based hypertext mark-up language. Survivors produce most of the material on the site. Afraid of official retribution, many anonymously contributed photos and stories of atrocities. Completely created through a volunteer effort, the site began with between 500 and 600 victims’ names but now lists more than 1,000. On the Chinese portion of the site, visitors can click on the names and read personal stories.

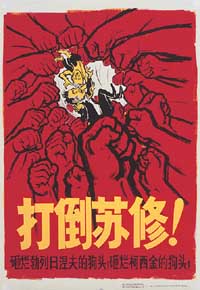

Smash the Soviet Revisionists!, Dadao Suxiu, proclaimed by the Shanghai Worker’s Revolutionary Rebel General Headquarters Fine Arts Battle, 1967, Shanghai |

Wang said that in 1986, Bajin, an eminent Chinese writer and critic, wrote an essay in which he suggested the construction of a Cultural Revolution Museum, similar to the Holocaust Museum that had been built in Washington, D.C. His proposal was ignored. But Wang said, “Now, if you can’t build a real one, you can build one in cyberspace. In China, about a half million people have Internet access. Now we think we can write our history in cyberspace.”

She emphasized that the phenomenon is not yet ready to be understood. “People still can’t believe such things happened in China––in Germany, Cambodia, yes, but not here. But they can happen and we can try to understand the reasons. The ones that have been given until now have been fake: ๋the teachers were rude to students’––this is like blaming the victim in the World Trade Center attacks. The attacks on teachers were a radical break with a tradition that revered teachers. We need to explain how this break could happen, but we must base it on facts. We need to collect the oral history, because other scholars don’t seem to be working on collecting these stories.

“Sometimes ordinary people in China don’t think their story should be recorded. It’s very difficult for Western scholars to reach this kind of people. And some Western scholars idealized Chinese reality––it’s difficult for people to understand these kinds of things. But now, as we gather the facts, maybe some people can theorize it, like Arendt theorized Nazism.”

Wang’s work is not limited to the Cultural Revolution. In addition to her language teaching, Wang has written a recent paper, titled “Oedipus Lex: Some Thoughts on Swear Words and the Incest Taboo in China and the West,” that examines the problem of cultural translation from the viewpoint of a few choice curses that Chairman Mao and U.S. Ambassador Patrick Hurley once hurled at each other.

The paper begins with the surprisingly different words and phrases by which English and Chinese joke about sex with other people’s mothers. From there it delves into the way each culture treats the violation of social boundaries through its stories and popular culture.

But while Wang continues to examine Chinese culture in this and other research, her passion for the memorial project and the potential it holds for allowing unheard thousands to write their own history, is paramount.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)