Sereno, team discover prehistoric giant Sarcosuchus imperator in African desert

By Steve KoppesNews Office

|

Paleontologist Paul Sereno has uncovered the remains of a giant prehistoric crocodile from the African Sahara that dwarfs its modern counterparts.

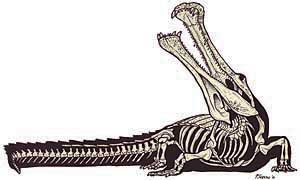

The animal, called Sarcosuchus imperator (“flesh crocodile emperor”), grew to a length of 40 feet and weighed eight tons, twice as much as an elephant. Modern crocodiles rarely exceed 14 feet and weigh no more than half a ton.

“This crocodile was probably capable of pulling down just about any dinosaur under the right circumstances,” said Sereno, Professor in Organismal Biology & Anatomy and a National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence. “It would have been a force to be reckoned with on the shoreline. It would have been a dinosaurÝs nightmare.”

Nicknamed “SuperCroc,” fossils of Sarcosuchus were first discovered by French paleontologist Albert-Felix de Lapparent and named in 1966 by France de Broin and fellow paleontologist Philippe Taquet. But until now, the animal was known only from fragmentary remains.

During expeditions to the T╚n╚r╚ Desert of Niger, Africa, in 1997 and 2000, Sereno and his research team recovered several partial skeletons of Sarcosuchus. They published a detailed description of the animal’s anatomy in the journal Science as part of the Science Express Web site on Thursday, Oct. 25. The paper also will be published in the Friday, Nov. 16 print issue of Science.

Sereno’s co-authors are Hans Larsson (Ph.D., ’00) of Yale University, Christian Sidor (Ph.D. ’00) of the New York College of Osteopathic Medicine and Boub╚ Gado of Niger’s Institut de Recherches en Sciences Humaines.

Sereno found the remains of Sarcosuchus in the same 110-million-year-old layer of sediments where he discovered Suchomimus in 1997. Suchomimus, a two-legged fish-eating predator, measured 36 feet long and 12 feet high at the hips. But it would have had to be on the alert for surprise attacks from the stealthy Sarcosuchus, Sereno said.

Like a modern-day gharial of India, Sarcosuchus would have kept a low profile in the water. When a gharial floats down a river, “if you’re lucky you see a couple of eyeballs and the nostrils,” Sereno said.

Sarcosuchus sports jaws studded with more than 100 bone-crushing teeth and an enormous, bowl-shaped snout. The unusual snout may have enhanced the animal’s sense of smell, or it may have been used to make sounds. Gharials, Sereno said, are highly communicative. “They’re vibrating and belching and growling and hissing all the time, sometimes even in the water,” he said.

Despite certain similarities to the much smaller gharial, Sarcosuchus went extinct with the dinosaurs and is not directly related to modern crocodiles. Nevertheless, measurements of living crocodiles that Sereno made in India and Costa Rica helped him to estimate the size of a full-grown Sarcosuchus.

He also studied the growth layers in the scutesˇthe armored plates along the back of Sarcosuchus. Examination of thin slices under the microscope revealed that the animals continued to grow throughout most of their 50- to 60-year life spans, twice as long as modern crocodiles.

As on three previous expeditions to Africa, Sereno’s team probed remote areas of the continent in temperatures reaching 125 degrees Fahrenheit for its fossil treasures. The team found that Sarcosuchus had plenty of crocodilian company in the broad rivers that flowed across the lush plains during the Cretaceous Period. Plying the same rivers were the doglike Araripesuchus and a newly discovered species, yet to be named, that attained a full-grown length of only two feet.

The National Geographic Society and the David and Lucille Packard Foundation funded the 2000 expedition, and the Pritzker Foundation was instrumental in the cleaning of the fossils in Sereno’s laboratory.

A cast of the six-foot skull of Sarcosuchus is on display in the lobby of the John Crerar Library. A more extensive exhibition is under preparation for the city of Chicago early in 2002.

The National Geographic Channel will air a special television presentation on Sarcosuchus and modern crocodiles on Sunday, Dec. 9. Sereno also will write about his discovery, and the article will be published in the December issue of National Geographic magazine.

More information about Sarcosuchus is at Project Exploration’s SuperCroc Web site at http://www.supercroc.com/index.htm.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)