Rockefeller challenged others to give to University

By Carrie GolusNews Office

Annie McClure Hitchcock |

“The best investment I ever made,” John D. Rockefeller’s much-quoted assessment of the University, would seem to imply a close, even controlling relationship. But while Rockefeller ruled his other major venture, Standard Oil, with an iron fist, his role at the University was much more hands-off.

Over two decades, Rockefeller donated more than $35 million to the nascent University, but he visited only twice and kept a surprisingly low profile during those visits.

Similarly, though Rockefeller bears the official title of “founder,” he insisted from the very beginning that other donors play a major role. Even his initial gift of $600,000 was promised only if the University could find enough Chicago supporters to raise an additional $400,000 within one year.

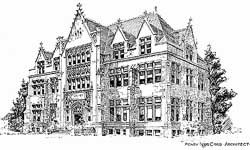

Walker Museum, Henry Ives Cobb, artchitect, architectural drawing, n.d. |

These lesser-known but equally important benefactors are the subject of an exhibition, “Building for a Long Future: The University of Chicago and Its Donors, 1889-1930,” currently on display in the Special Collections Department of the Joseph Regenstein Library. The exhibition brings together photographs, letters, memos, newspaper clippings and ephemera from Special Collections as well as the general library collection.

“Building for a Long Future” is the brainchild of John Boyer, Dean of the College and unoffi-cial University historian. Boyer has written several papers on different aspects of University history, such as the sit-ins of the 1960s and the role of the early trustees, but this exhibition marks the first three-dimensional realization of his scholarship in collaboration with the staff of Special Collections.

Many of the donors’ names––Cobb, Bartlett, Blaine, Hitchcock, Mandel, Rosenwald, Ryerson, Swift, Walker––read like a campus map of the early University. But while their names are familiar, their stories are not. For example, George Walker (Walker Museum) was a real estate developer who fell out with the Baptist establishment over the deeply controversial act of dancing. Martin Ryerson (Ryerson Physical Laboratory), a lawyer and businessman, retired in his 40s to devote himself to philanthropy and covering the walls of his Hyde Park mansion with Impressionist and Old Master paintings. Helen Culver (Hull Biological Laboratories) also is known for the donation of her cousin’s home, Hull House, where Jane Addams established her settlement house.

“The donors reflected the city of Chicago at the time,” said Daniel Meyer, Associate Curator of Special Collections and University Archivist. “They represented a cross-section of commercial and industrial interests––banking, trading, real estate, meat-packing, shipping––as well as their cultural and civic interests.”

The donors also reflected the diversity of religious belief in the Chicago area. “In a curious way, the story of the early donors is an expression of the fine line between sectarianism and secularism,” Boyer said. “The University was founded by Baptists from Chicago and across the University, but many of the Chicago donors were not Baptists––they were from other Protestant denominations, Jewish or free thinkers.”

Unusual for the time, many of the early donors to the University were women, including Culver, Anita McCormick Blaine (Blaine Hall) and Annie McClure Hitchcock (Hitchcock Hall). “The reason for that is the University was co-educational from the beginning,” said Meyer. “Women were admitted on an equal basis with men, which was very distinct from older eastern universities. So women are a very important part of the story.”

Boyer said, “It’s interesting to look at what the donors thought they were doing by giving money to the University. Each had a different vision. Some donors, for example, were interested in establishing a great liberal arts college, on par with Harvard or Yale, to which women and men had equal access. Meanwhile, other donors like Martin Ryerson, who gave much of the money for the physics building, were interested in creating a great research university.”

What all the donors had in common was the “booster spirit,” a sense of civic pride in the rapidly developing city. During the 1890s, Chicagoans were engaged in establishing all types of civic and cultural institutions––the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Historical Society, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Newberry Library––to say nothing of the World’s Columbian Exposition. And just as Chicago, then known as the “great city of the West,” needed great cultural organizations, it also needed a great university, Meyer explained: “The University of Chicago had the city’s name attached––it was an emblem of the civic pride of the city of Chicago.”

While the section of the exhibition on the founding donors could easily have been called “Buildings for a Long Future,” its scope actually is much larger, taking in scholarships, fellowships, lectureships, prizes and donations to the University library. One noteworthy gift was the Ebenezer Lane Library, the only book collection to have survived the Chicago fire.

“Building for a Long Future” is on display until Monday, Dec. 31, in Special Collections. The hours are 8:30 a.m. to 4:45 p.m., Monday through Friday and 9 a.m. to 12:45 p.m., Saturday. Members of the public also may view the exhibition, and public passes may be obtained from the Privileges Office at the library.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)