Professor Isenbergh embraces digital revolution to teach law

By Peter SchulerNews Office

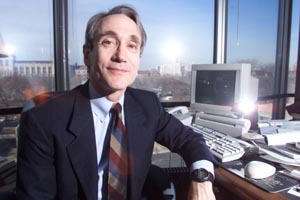

Joseph Isenbergh, the Harold J. and Marion F. Green Professor of International Legal Studies in the Law School |

Most members of the legal and teaching professions have been famously slow to adapt to the digital revolution. Professor Joseph Isenbergh is definitely an exception.

Isenbergh, the Harold J. and Marion F. Green Professor of International Legal Studies in the Law School, sees the shift from paper to cyberspace as “the greatest intellectual accomplishment of the last part of the 20th century, and like the printing press, one of the most prodigious of human creations.” One of the foremost tax experts in the United States, Isenbergh’s three-volume treatise, International Taxation, is essential reading in law schools and among tax practitioners.

This year, he led a pilot program at the Law School in which his students use an electronic textbook, “goReader,” for his classes in tax, finance and corporations. The book-sized device contains all the course texts, study guides and supplementary materials.

How has this shift to digital changed the way you work?

I think the transformation of the materials with which I work regularly from some sort of printed paper to digital and electronic forms is inevitable and overall tremendously advantageous. You can tell just by looking around my office that I’ve always had a very uneasy relationship with paper. And I aspire to purge paper from my life, totally if I can. And despite appearances–all this clutter–in some aspects of my work, I have accomplished that. For example, almost all of my writing is now done on a computer, but more than that, I don’t simply write the books on a computer, I produce camera-ready page proofs of all my books. So I literally produce the whole book down to its appearance on the printed page. Other than a printed copy for proofreading, the first time I see a printed page is the first time my readers do. It’s all essentially digital.

So you are gradually removing paper from your life?

What you see on my desk are papers that have evolved from other things and that are left over. I recently acquired a scanner. I’m now scanning all sorts of my papers. For my pleasure reading, I still read paper books. But in my research, I rarely now venture into the library stacks. I do 90 percent of my research from online databases that now populate the World Wide Web.

And the effect on your teaching?

In my teaching there has been much less encroachment of digital information. Until very recently, I sent out paper materials to the students. And when I have a notice for the students, I send out a paper notice that’s posted on a physical bulletin board and students huddle around it. I would look to transform these routine elements of teaching to digital to the same extent that I have transformed my research and scholarship. But it’s proven much more difficult, though I no longer get hand-written examinations on the classic blue books. All the exams are printed out from answers the students have composed on their laptops. And I rarely see students taking notes in class by hand. Instead they type into their computers. Still, the basic teaching materials are distributed as photocopies or as conventional casebooks and paper books, except for the “goReader” project.

But don’t most people find reading from a computer screen a rather unpleasant experience?

My initial impression of the “goReader” is that the conception has run far ahead of the execution. In theory the students need only this one thing. The problem is a basic hardware issue: the resolution of the print on the “goReader” pages isn’t crisp enough, or more accurately, not as crisp as conventional casebooks. And the scrolling speed is slow and somewhat balky. All of these problems are bound to be surmounted. Rather like what it must have been like to drive a 1902 Oldsmobile. You were impressed, but on cold days when your Oldsmobile wouldn’t start, you’d still go to your stable and hitch up your horse because you had to get somewhere. But when you get a much more effective, powerful, high resolution unit, this method of study will work well.

How do you foresee the transition to digital among teachers and students?

People do have habits and there is an attachment to pens and paper books. That’s why I do research on a computer monitor but I do my pleasure reading from a printed book. The monitor resolution is a fraction of the quality and sustained reading is impossible. I don’t think there will be a significant, across the board embrace of digital forms of media until they become easier on the organism than they are now. In all the areas in which I’ve been able to shift to digital methods of work and writing, teaching, even sustained reading in a few instances, my output has improved.

Are you one of only a handful of faculty members at the Law School who have moved into cyberspace with this level of enthusiasm?

Some of my colleagues resist for different reasons. They still don’t impute to documents and research materials in cyberspace the same authority as print. Some think that perhaps because of typographical errors introduced in the process that citations in an online database are not really trustworthy, and reliance on online sources betoken some lack of ultimate scholarly purpose. I know that until recently in the introductory program on legal research, the students were discouraged and sometimes prohibited from going straight to online databases to find materials. Perhaps the idea was to create a map of the relationships and hierarchy of these materials in the students’ minds that’s more easily derived from hardbound books. When I cite authority for my books, I rely almost exclusively on electronic data. For purposes of citation and browsing and research, I find the digital environment matchless.

Isn’t there also a pleasing, serendipitous aspect to working with books on library shelves?

I’ve found adventitious encounters with unexpected material in cyberspace that are just as inspiringly interesting. When I was a student, I was a compulsive reader of the book that happened to be next to the book I was really looking for, and that probably delayed the onset of my career to some extent. And I’m now becoming a curious peruser of enticing links in cyberspace and have stumbled onto treasure troves of historical and comparative materials I wasn’t originally seeking.

Why do you think you found all this new technology so appealing?

My uneasy relationship with paper made the switch easy for me. And I wasn’t a good typist. In a logistical and ministerial sense, a good number of my colleagues managed their papers’ existences far better than I, and so they perhaps have more intellectual capital invested. And that may explain why I gently view them as Luddites and they probably view me as a space cadet.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)