Consortium reports on keys to better learning

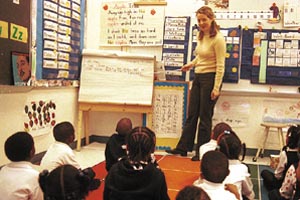

Learning improves for Chicago public elementary students when they are challenged by class assignments, when their school programs are organized and coherent, and when teachers incorporate interactive methods in their teaching, according to a series of reports released last week by the Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University. According to reports recently released by the Consortium on Chicago School Research at the University, interactive teaching methods––such as those used at the North Kenwood-Oakland Charter School, which the University established––are one factor in improving public elementary school children’s learning. |

The consortium’s studies are part of a six-year research program, the Chicago Annenberg Research Project, which documents and analyzes the activities and accomplishments of schools taking part in the Chicago Annenberg Challenge. In 1995, the Annenberg Foundation awarded a five-year grant of $49.2 million to establish the Chicago Challenge, with an additional $100 million in matching funds pledged by local donors.

The Chicago Annenberg Challenge distributes those funds among networks of schools and external partners. Its mission is to improve student learning by supporting intensive efforts to reconnect schools to their communities, restructure education and improve classroom teaching.

“Researchers at the consortium examine academic progress in the Annenberg Challenge Schools in two ways,” said Anthony Bryk, the Marshall Field IV Professor in Sociology and Director of the Consortium on Chicago School Research. “First, we undertake trend analyses of learning gains on basic skills as measured by standardized tests. Second, we are complementing these test score analyses with an in-depth longitudinal study of the quality of intellectual work occurring in a sample of Annenberg Challenge schools.”Among the three reports issued last week is “Authentic Intellectual Work and Standardized Tests: Conflict or Coexistence.”

The report, written by Bryk; Jenny Nagaoka, a Research Associate at the consortium; and Fred Newmann, professor emeritus of curriculum and instruction at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, notes that challenging instruction improves learning for all students, regardless of their abilities.

Bryk said people who believe this is a trade-off between challenging, engaged lessons and an approach that emphasizes repetition and drill often see a false dichotomy. When students are asked to write essays rather than fill in grammar and punctuation worksheets, they perform better because they are able to apply what they learn about language skills in a project they care about, he explained.

Similarly, when students are asked to use mathematical understanding in interpreting a real life experience, such as reading a stock market table, they find mathematics more engaging and learn more.

The study found that on average, based on standardized test scores, students receiving high quality assignments learn nearly twice as much in reading than do students doing more routine work. In mathematics, the gain was almost as high.

In another study, co-authored by Bryk; Newman; BetsAnn Smith, an assistant professor of educational administration at Michigan State University; and Elaine Allensworth, a Senior Research Associate at the consortium, the researchers documented the importance of coherence in organizing a school’s instructional program. Clearly stated goals with a common instructional framework often create the teamwork and atmosphere that can propel student achievement.

Ironically, many add-on programs intended to enhance the school experience, such as taking students on field trips, sometimes take time away from instruction without adding to learning, the team found. Principals of schools with improving test scores were careful about what new programs they adopted. “You can, in fact, have too many resources,” one principal said.

In schools where teachers and administrators reported substantial increases in coherence, test scores increased by 19 percent in reading and 17 percent in mathematics between 1995 and 1997, according to the report.

A third study, “Instruction and Achievement in Chicago Elementary Schools” co-authored by Julia Smith, associate professor of education at Oakland University; Valerie Lee, professor of education at Michigan State University; and Newman, found that students from a wide variety of backgrounds perform well when teachers use interactive approaches.

Teachers with graduate education tend to emphasize interactive approaches, while teachers with bachelors’ degrees tend to emphasize classroom drills as a form of learning, the study found.

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)